Griffith Park’s little-known history as a prison camp for Japanese, German, Italian immigrants

- Share via

At the northern end of Griffith Park, the Travel Town Museum showcases old trains and locomotives.

Few people are aware that a much darker history lives on this spot, where Japanese, German and Italian immigrants were unjustly imprisoned during World War II, often on baseless suspicions of being “potentially dangerous enemy aliens.”

Now, that history is being recognized at Travel Town with a plaque telling the stories of the prisoners, including Rafu Shimpo newspaper typesetter Katsuo Nagai and Italian fisherman Ralph Averga.

Nagai was arrested because of an alleged affiliation with the Hollywood Japanese language school, the plaque says.

Averga was 48 when he was removed from a fishing boat in San Pedro, according to the plaque, which displays his mug shot and fingerprints.

“These men weren’t prominent individuals within their communities. They were regular people,” said Russell Endo, a retired professor of sociology and Asian American studies at the University of Colorado. “We wanted to show the extent to which the government overreached its authority and went after everyone.”

Endo has documented 101 Japanese, 21 German and four Italian prisoners who were incarcerated at the site at some point between February 1942 and August 1943, though he said there were almost certainly more.

The Los Angeles Times will no longer use “internment” to describe the mass incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry during World War II.

Three sets of barracks and 50 Army tents could hold up to 550 people and were enclosed by two 10-foot-high fences with barbed wire, according to Endo and Travel Town archivist Linda Barth.

Like the much larger prison camp at the Santa Anita racetrack in Arcadia, Griffith Park was a way station for people who ended up in long-term prison camps.

Under proclamations signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in December 1941, immediately after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, the immigrants were arrested and forced to appear before an “alien enemy hearing board.”

Some were released or paroled. Others were imprisoned “based on weak evidence or unsubstantiated accusations of which they were never told or had little power to refute,” according to the National Archives.

Under a separate executive order that Roosevelt issued on Feb. 19, 1942, about 122,000 men, women and children of Japanese ancestry were sent to incarceration camps.

About 18,000 lived in horse stalls at Santa Anita before moving to remote, windswept prison camps like Heart Mountain and Manzanar.

At a ceremony on April 20 in Griffith Park to dedicate the new plaque, descendants of men who were imprisoned there stood alongside Harumi “Bacon” Sakatani and Takashi “Tak” Hoshizaki, Japanese Americans incarcerated with their families as teenagers.

The plaque was a gift from the Griffith J. Griffith Foundation, which supports park projects, and was created with the help of L.A. recreation and parks officials, the Travel Town Museum Foundation, the Tuna Canyon Detention Station Coalition, the Japanese American National Museum and the Los Angeles Breakfast Club.

In a tweet, City Councilmember Nithya Raman, whose district includes Griffith Park, expressed hope that “a problematic past can still give way to a more just, educated, and equitable future.”

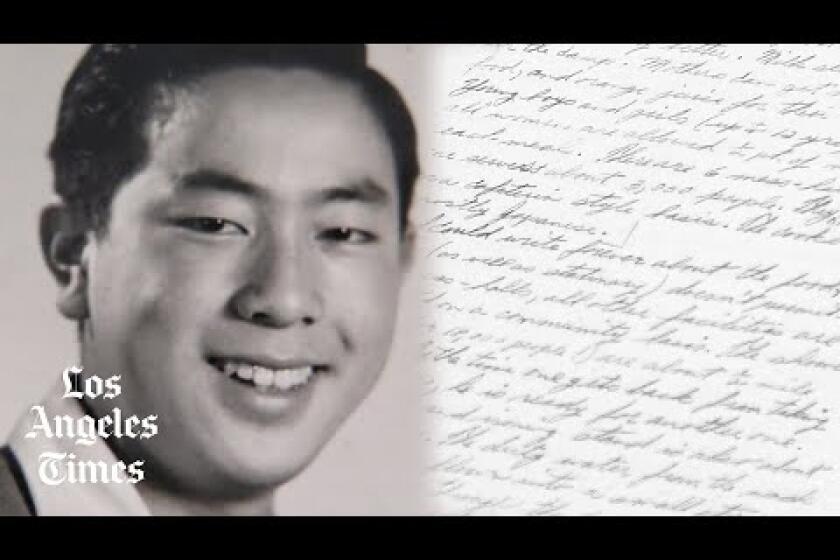

Kathy Masaoka’s grandfather was in the first group of 77 Japanese immigrants imprisoned in Griffith Park.

Sochi Kadota worked as a day laborer before eventually buying a 10-acre vegetable farm. After he was taken away, his wife and 10 children had to sell the farm and were soon incarcerated themselves at Gila River near Phoenix.

Masaoka has no idea why her grandfather was arrested.

“This was a part of our history that was never talked about, because it elicits such shame and pain,” Masaoka said. “But it’s a story that needs to be told so it can never happen again.”

After they were released, most of the family settled in the Midwest.

Japanese Americans were held at the race track before being shipped to incarceration camps. My uncle’s letters reveal the indignities of living there.

Kadota had a hard time rebuilding his life, Masaoka said. He worked as a janitor and then became a homemaker while his wife worked at the Fuller Brush Co. He died in 1968 at age 88.

“He was the head of a household and had a certain lifestyle and all that was taken away,” said Masaoka, 74, of Silver Lake. “He had to adapt.”

Sigrid Toye was 3 years old when her father, a German immigrant, was arrested on Dec. 7, 1941, after FBI agents searched their home near Griffith Park.

Her mother didn’t know why he was arrested.

Eugen Banzhaf stayed at Terminal Island for a few weeks before being moved to Tuna Canyon, Griffith Park and then a prison camp in Stringtown, Okla.

Toye said her mother had a hard time finding a job because of her thick German accent. They survived by selling their possessions, including their home.

After Banzhaf was released in 1943, he and his family settled just outside Griffith Park. He struggled to find steady employment, often relying on temporary jobs, from working at a brokerage firm to raising chickens.

Toye became a clinical psychologist. Her father died in 1992 at age 91.

“A lot of my life was defined by that moment,” said Toye, of Santa Barbara. “I’m not here because I’m angry or want some sort of payment. I’m here because no one spoke up for my parents, and I’m doing that now.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.