Column: For Santiago Nieto, all roads in California lead to farmworkers

- Share via

When I think of Santiago Nieto and his walks, I imagine him as the knight from Quixote de la Mancha, who in his crazy wanderings around the world mistakes windmills for menacing giants. But Nieto isn’t crazy, actually, he’s painfully sane and has decided to put his time and effort into helping California farmworkers.

His way of calling attention to the impoverished conditions in which hundreds of thousands of California farmworkers live, the vast majority of them migrants from Mexico and Central America, is through his campaign “Por ti campesino, yo camino” (“For you farmworker, I walk”), which leads him through mountains, rivers and deserts. He walks in the rain as well as in the 115-degree heat of the Central Valley.

On his last walk, for which he traveled a total of 530 miles and crossed 27 cities on his way from Los Angeles to Sacramento, he was looking to raise $100,000 to give to Cirugía Sin Fronteras, which at that time needed support to continue helping working families hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The coronavirus was cruel to the poorest, to the marginalized, to those who had nothing,” Nieto tells me, recalling that march, which began on Sept. 16 (Mexican Independence Day) and ended on Oct. 16, 2020.

After 320 miles and 23 days on the road, I interviewed Nieto once again. I found him skinny, sunburned and thirsty. “Of the $100,000 we wanted to raise, we only got $22,000,” he told me, in a voice between disgusted and disappointed.

“It’s like farmworkers and their families don’t exist, like nobody cares what happens to them,” he told me, speaking out of both frustration and courageous determination as he rubbed his blistered feet.

It touched me to see him enter dusty towns surrounded by strawberry fields with a dozen followers at his side. He reminded me of the scene where Forrest Gump starts running across the country. But unlike Tom Hanks’ character, Nieto does have a cause, and a very specific one: To help raise funds for Cirugía Sin Fronteras, whose mission is to help low-income people without health insurance obtain low-cost surgeries.

A farmworker eats during a break at camp.

Based in Bakersfield, Cirugía Sin Fronteras says that it has provided access to healthcare for more than 3,500 people; given out more than 900 food baskets to families in need; and distributed economic relief to 49 families through its COVID-19 emergency aid program; linked more than 4,500 families with community resources; and provided preventive health education and chronic disease management to more than 6,000 people.

Knowing and seeing Santiago on these journeys has had a profound impact on me, because he has always given me the impression that there is a supernatural force behind him.

“It’s simple solidarity,” he tells me as we chat on the side of a dusty road in Tulare County. As he rests, in the distance dozens of workers can be seen hunched over a field dotted with strawberries.

“When I feel like I can’t take it anymore, I think of Don Abraham, a 73-year-old man, and I think that he should be playing with his grandchildren instead of continuing to pick strawberries at 107-degree temperatures. When I remember the image of him, I feel bad, because I realize that the subject is like the elephant that is in the room and that nobody wants to turn around to see.”

Nieto speaks slowly as he tries on a new pair of sneakers.

“Everyone prefers to turn the other way, even though they have sacrificed their families to put food on our tables. I think we have to put food and health in their homes.”

He pauses as he watches a plane drop insecticide from a very low altitude. “Do you think that doesn’t make them sick?,” he tells me, staring at the vehicle passing overhead.

Between abundance and poverty

According to the California Department of Food and Agriculture, one-third of the vegetables and two-thirds of the fruits and nuts produced in the United States are grown in the Golden State. And to get an idea of the profits that this sector generated in 2021, it is enough to say that counting only the top 10 agricultural products, among them dairy, grapes, almonds, strawberries, pistachios, lettuce, tomatoes, nuts and rice, California farmers took in more than $32 billion.

In total, the state’s farms and ranches generated $51.1 billion in 2021.

But this economic prosperity does not reach the more than 420,000 workers who make this gigantic agricultural production possible. Farmworkers in California earn an average of $26,000 per year, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The organization Center for Farmworker Families estimates that 75% of California farmworkers are undocumented. Approximately one-third of the agricultural labor force are women, ranging in age from their teens to their 60s. Farmworkers are often subjected to sexual insults, groping, threats, beatings and even rape in the fields. In California, 80% of farmworkers say they have experienced sexual harassment.

“Yes, California is a rich state, but no one turns to look at their workers,” Nieto says as he prepares to resume his march.

So far Nieto has made five walks through the state and is preparing his sixth, which will start from the Mexican Consulate on Sept. 15 and will try to reach Bakersfield seven days later. On that occasion, he’ll be seeking not to raise money but to raise awareness about the poverty in which hundreds of thousands of farmworkers live in the richest state in the United States.

For the wrong reasons

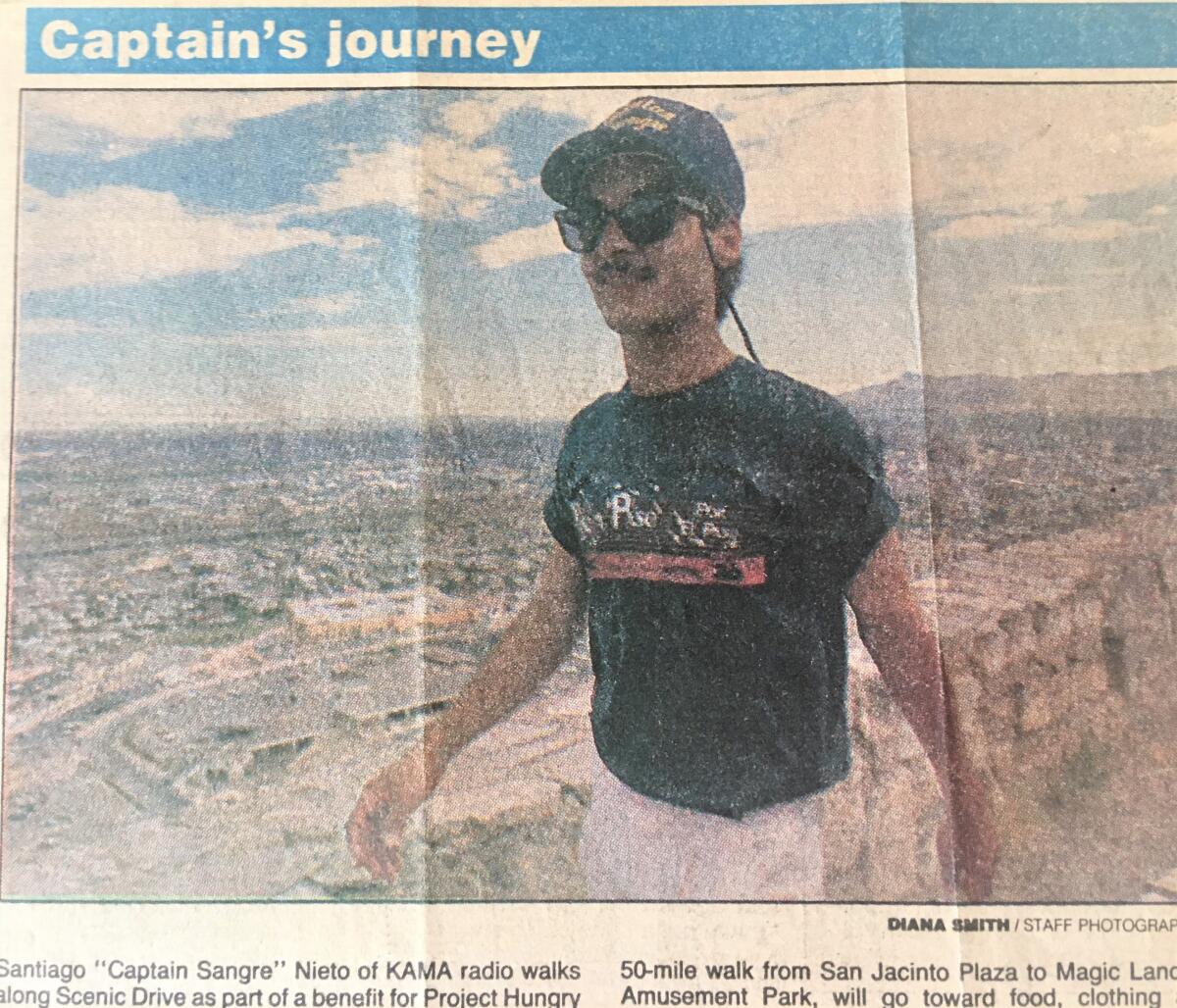

Originally from Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Nieto began his professional career at KAMA, El Paso’s first Spanish-language radio station.

“That’s when I learned that to keep radio listeners you have to do a circus and theater,” says Nieto, recalling the multitude of events he held to entertain audiences while helping the neediest.

“I would do radio marathons to get orthopedic shoes for children with mobility problems, broadcast day and night on the roof of 7-Eleven stores to raise funds for numerous causes. On another occasion, when we needed to give away a van to a nursing home, we put a vehicle on a crane that lowered a few inches each time someone donated something,” he says.

But all this was done for the wrong reasons, admits Nieto, who is the son of a well-known Mexican politician. “I wanted fame, I wanted popularity, I wanted to feed my ego.”

Back in Los Angeles, where he was coordinator of “Don Cheto al Aire” Radio Network, Nieto was approached by the Cirugía Sin Fronteras Foundation, asking that Don Cheto, one of the most popular characters on Spanish-language radio, make a public service announcement to raise awareness of Cirugía.

Nieto not only managed to get Don Cheto but other celebrities such as Rosie Rivera, Larry Hernández, Ana Barbara, Omar Chaparro and Juan Rivera, among others, to record videos and public service announcements. But that did not fulfill his aspirations to do something more.

“One night I was sitting watching the movie ‘The Way,’ about the famous Camino de Santiago and I felt that this was my call, that I had to do something like that … so I ran downstairs and told my wife what I was thinking and she said, ‘You’re crazy.’”

But the idea stuck in his head.

“I knew in my heart that this was what I had to do, but not because of fame, popularity or ratings, but because that was my calling,” says Nieto, who confesses that he is not moved by religious sentiments, but by the feeling that among the faces of the men and women he sees working could be that of your mother, your sister, your aunts, your grandmothers or your brothers.

“They are the faces of our people, and I cannot ignore that.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.