She gave up sex for a year and gained control of her life

- Share via

On the Shelf

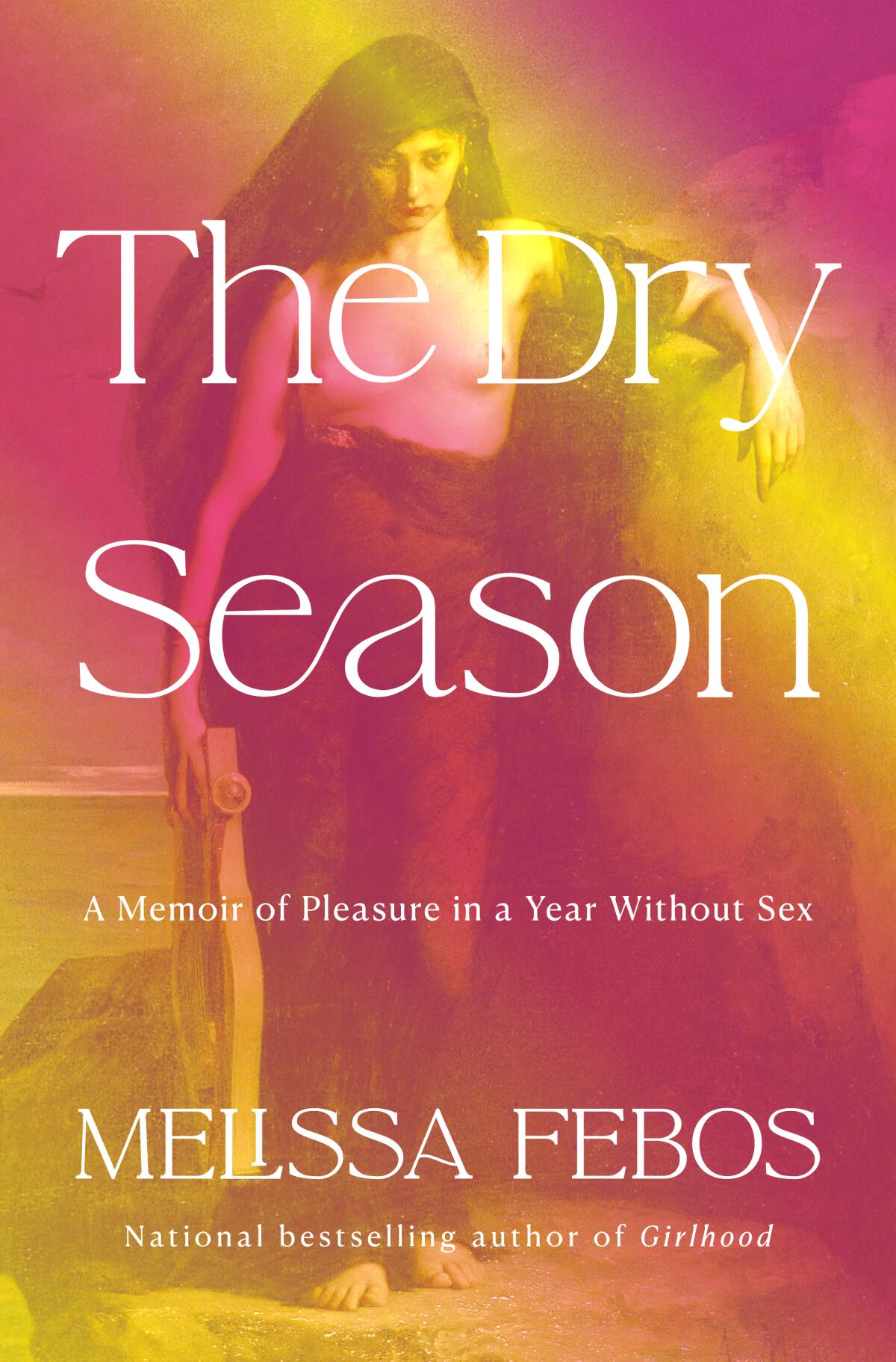

The Dry Season

By Melissa Febos

Knopf: 288 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

After jumping from one relationship to the next, Melissa Febos found herself in bed with a woman she scarcely knew. “Though I stubbornly tried to prove otherwise, for me, sex without chemistry or love was a horror,” Febos writes in her new book, “The Dry Season.” “A few weeks later, I decided to spend three months celibate.”

On an unseasonably warm and sunny day in Seattle, I met Febos to talk about the surprising pleasure when those three months turned into a full year of celibacy. “I had been thinking of this time as a dry season, but it had been the most fertile of my life since childhood,” Febos writes. “I had run dry when I spent that vitality in worship of lovers. In celibacy, I felt more vital, fecund, wet, than I had in years.”

While giving up physical intimacy might sound like the opposite of titillating, those familiar with the demands of monogamy and motherhood could recognize the erotic potential of solitude. “A friend of mine took a trip without her toddler and said that the time she spent waiting in line to board was borderline erotic because it was a quiet time and space that she hadn’t had in years,” Febos said.

At 44, Febos has already established herself as a prolific, critically acclaimed and bestselling writer of memoirs and creative nonfiction. “The Dry Season” is her fifth book. Her first, “Whip Smart,” chronicles her time as a professional dominatrix. “Abandon Me” tells of losing herself in a toxic relationship, struggling with addiction and discovering her biological father, and “Girlhood” is a collection of essays about being in a body that no longer belongs to her. Her most recent, “Body Work,” is a craft book on embodied writing.

The physical body is clearly central to her writing — how it affects our work, our personal relationships and, most importantly, our relationship with ourselves. In a 2022 essay for the New York Times Magazine, Febos described her decision to undergo a breast reduction as a means to reclaim herself. In a society where bodily autonomy is under active and devastating attack, Febos’ work is not only provocative, it’s absolutely necessary.

In the flesh, it’s difficult to imagine Febos as anything but perfectly in control. She is warm, compassionate and easy to laugh. She’s proud of the work she’s done in recovery from addiction. Much of “The Dry Season” takes inspiration from programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous, where the desire for a substance is in reality a desire to be closer to God.

It’s unsurprising then that Febos discovered that nuns were some of the first women to find freedom in celibacy. She was particularly interested in one medieval sect called the Beguines, who “took no vows, did not give up their property, and could leave the order anytime. They traveled, preached, and lived more independently than most women in the western world.” But it wasn’t necessarily that they rejected sex, as Febos writes, but rather a life focused on men. “The Beguines did not just quit sex, and it is likely many did not give up sex at all. They quit lives that held men at the center.”

Miranda July has hit a creative, life-giving stride, at 50, with her deeply funny and achingly true new novel, ‘All Fours’ -- her first in almost 10 years.

When Febos told a friend that she was going to take a break from sex, she rolled her eyes. It’s assumed that sex and love addicts are usually straight people, that it’s heterosexual men who are sex addicts and heterosexual women who are love addicts. “There was part of me that hoped I might be SLA [sex and love addict], because it could’ve been an easy answer,” Febos said.

Febos works to dismantle heteronormative stereotypes about love and sex in this book, quoting writer Sara Ahmed: “When you leave heterosexuality, you still live in a heterosexual world.” Later in the book, she discusses the uniquely queer and effective partnership of Leonard and Virginia Woolf. “I didn’t want to simply relocate within compulsory heterosexual gender roles,” she writes. “I wanted to divest from them.”

Febos said playfully, “I thank God every day that I am not straight. But we’re still socialized to behave a certain way. We all live under patriarchy. But I never had fantasies of marriage or of being a wife,” Febos said. “My dream was always to be a writer, an artist.”

In “The Dry Season,” Febos processes some of the experience of being celibate through her friendship with a younger queer woman named Ray. Though there is sexual tension between them, the reconfiguring of desire helped Febos realize that some impulses aren’t worth acting on. Febos has taught creative writing in the Master of Fine Arts program at the University of Iowa for the past five years and considers herself lucky that she’s never felt attracted to her students. “Teaching helps me to be a better writer,” she said. “But it is partly about seduction, about being able to hold someone’s attention, to get them to feel something you feel passionately about or to help them see something they haven’t recognized before.”

Kathleen Hanna’s memoir, ‘Rebel Girl,’ is a bold portrait: a crucial book about feminist politics and art and a tender examination of a woman who survived abuse and sexual assault.

For Febos, the decision to take a step away from sexual intimacy is similar to the experience of understanding a text. “There is a difference between how you react to a text and how you analyze a text,” she writes. “You can be attracted or repelled by the content and still think critically about the response, about your own relationship to the text. As in love among humans, we cannot appreciate a text until we really see it, and in order to see it we have to get out of the way.” In other words, to truly understand your desire, you have to spend some time apart from it.

“The Dry Season” is no marriage plot. Even though Febos’ wife, poet Donika Kelly, who Febos met after her period of celibacy concluded, appears briefly at the end of the book, Febos resisted having her there at all. “That was truly not the point,” she said laughing, “to say, ‘Look, it all turned out great in the end!’ ” I told Febos that many women had confided in me (in response to reading Miranda July’s novel “All Fours”) that they felt obligated to participate in sex in their marriages with men. “That’s really the point of this book,” she responded. “Why are you having sex if you don’t want to be having sex? This radical honesty not only benefits you but it also benefits your partner. To me, that’s love: enthusiastic consent.”

Febos has reached the point in her career where she is in control. She told her agent that she would write a brief proposal for this book and nothing more, and it sold quickly. This is a freedom many writers will never achieve. Perhaps it’s due to the fact that Febos works not only on her craft but on herself. “My subject is myself, so this kind of work, in my relationships and with myself, is germane to my writing,” she said. Her inner work has been a wise investment, leading Febos to feel more freedom in her authorial vision, perhaps even moving toward fiction. “Writing is a process of integration for me,” she said. “I am so comforted by all of life’s surprises.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.