The story of a Leonard Cohen song in ‘Hallelujah’

- Share via

Hello! I’m Mark Olsen. Welcome to another edition of your regular field guide to a world of Only Good Movies.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

2022 Halftime Report. As we enter July, Justin Chang assessed the year to date in movies. Among his picks for the best so far are Terence Davies’ “Benediction,” David Cronenberg’s “Crimes of the Future,” Audrey Diwan’s “Happening,” Hong Sang-soo’s “In Front of Your Face,” Steven Soderbergh’s “Kimi,” Robert Eggers’ “The Northman” and S.S. Rajamouli’s “RRR.”

Regarding the current state of theatrical moviegoing, Justin wrote, “I’m gratified by how many good and even great movies I’ve seen released in the first half of 2022 alone. I’m also dispirited, if hardly surprised, by how quickly so many of them evaporated from theaters, assuming they played in theaters in the first place. … But no movie lover — and no lover of theatrical moviegoing — can afford to take this cherished pastime or their favorite venues for granted. I’m as heartened as anyone by the record-setting box office for ‘Top Gun: Maverick,’ but movies without blockbuster budgets, franchise hooks and/or Tom Cruise face as uphill a battle as they ever did.”

70 mm festival. The American Cinematheque is launching a tribute to the widescreen format with a series running throughout July. Alongside newly struck prints of “Airport” and “Spartacus” and the Cinematheque’s own recent prints of “Lawrence of Arabia” and “2001: A Space Odyssey,” the series will include “Baraka,” “The Master,” “Malcolm X,” “Streets of Fire,” “Howard the Duck,” “The Wild Bunch,” “Vertigo” and more. I already bought tickets for “Short Cuts,” shown on a print that is billed as not having been screened theatrically for 20 years.

For the Fourth of July weekend, the Cinematheque also has a series of films with scenes of fireworks, including “Summertime,” “To Catch a Thief,” “Police Story,” “Blow Out,” “Brokeback Mountain,” “Hana-Bi” and “Cape Fear.”

Hollywood producer gone bad. Paul Schrader once said, “Bad people come to Hollywood in order to be bad.” This week, Amy Kaufman and Meg James published a blockbuster exposé of producer Randall Emmett, who, while best known for dozens of low-budget action films, was nevertheless nominated for an Oscar for his work on Martin Scorsese’s “The Irishman.”

In particular, it was Emmett who was cranking out films with Bruce Willis as the actor’s health declined. The story has details not only on Willis but also on what it takes to get actors like Robert De Niro, Mel Gibson and Al Pacino into a movie of questionable quality. (Answer: money and perks such as private jets and luxury vacations.) The story also includes allegations of sexual, financial and just plain moral misconduct that seem straight out of a Hollywood potboiler. It all makes for a riveting read.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

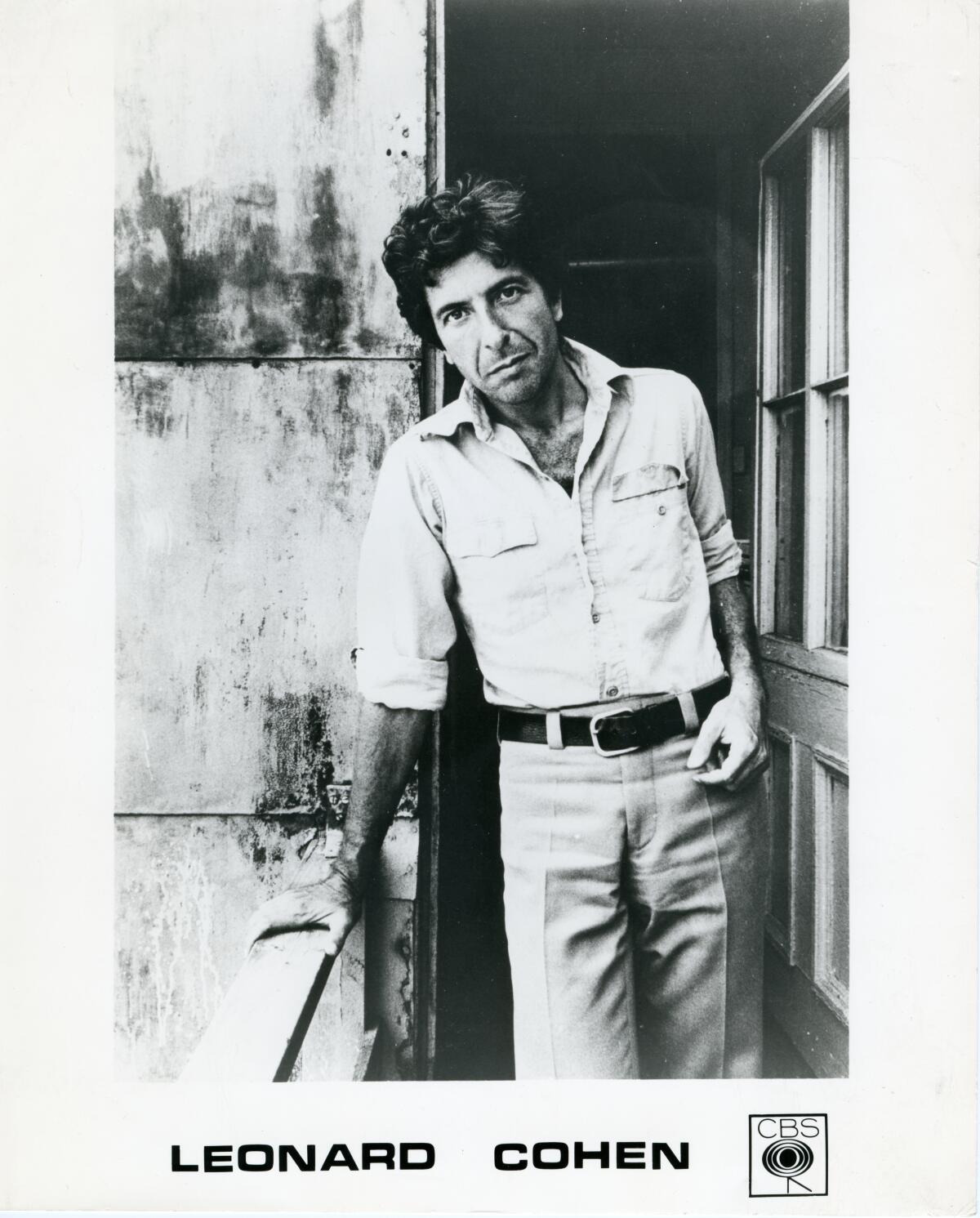

‘Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song’

Directed by Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine, the documentary “Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song” is exactly as billed, an examination of the singer-songwriter’s now-classic composition, which took Cohen years to complete; was on an album initially turned down by his record label; and, over the years, became a new standard. The film is in limited release now.

For the New York Times, A.O. Scott wrote, “Cohen wasn’t one to offer comfort. His gift as a songwriter and performer was rather to provide commentary and companionship amid the gloom, offering a wry, openhearted perspective on the puzzles of the human condition. ‘Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song’ is, accordingly, not a movie designed to make you feel better about anything, except perhaps Cohen himself. But this generous documentary is nonetheless likely to be a source of illumination for both die-hard and casual fans, and even to people who love Cohen’s most famous song without being aware that he wrote it.”

For AP, Lindsey Bahr wrote, “It’s an interestingly stitched together film that starts at the end — his final performance in 2013, singing ‘Hallelujah,’ of course — and rewinds to the beginning of his songwriting career to trace how he got there. It feels, in some ways, like two different films: The first part is a standard biographical documentary that then shifts focus to ‘Hallelujah’s’ resurrection outside of Cohen, before finally turning attention back to Cohen and his triumphant final tour. As the title says, it is a journey and a long one at that.”

For the Wrap, Steve Pond wrote, “The result is an affectionate and open-hearted tribute to Cohen and his work, with an emphasis on the one song that might lure in the occasional uninitiated viewer. The song ‘Hallelujah’ may be the way into Cohen’s world, but that world is far richer and more singular than any one song, and the filmmakers are looking for the big picture here. … ‘Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song’ is smart enough to embrace that mystery and that beauty, and to know that there’s far more to Cohen than can be summed up in four, or seven, or even 150 verses.”

For Rolling Stone, David Browne wrote, “‘Hallelujah’ isn’t a definitive, life-spanning doc on Cohen’s life, nor does it claim to be, but the tale of ‘Hallelujah’ serves as a metaphor for Cohen’s life. The way he labored over the song is of a piece with the years he would take between albums, and ‘Hallelujah’ itself encapsulates the way the solemn and the sensuous could each find a home in the same Cohen song. His pop-star makeover, from early in his career to later in life, was as unlikely as the song itself becoming part of the 20th century song canon. The movie makes it easy to imagine a future in which AI robots will be singing it to each other in the year 2350, no matter what’s left of the planet itself.”

‘Mr. Malcolm’s List’

The feature debut for director Emma Holly Jones, “Mr. Malcolm’s List” is written by Suzanne Allain, adapting her own novel. Set in Regency-era England, the story concerns Mr. Malcolm (Sope Dirisu), who has a list of qualifications he is looking for in a wife. When he rejects Julia (Zawe Ashton), she hatches a scheme that involves the charming Selina (Freida Pinto) to get back at him. The film is in theaters now.

For AP, Jocelyn Noveck wrote, “Austen herself has nothing to do with ‘Mr. Malcolm’s List,’ the clever, entertaining and delectably pretty new film starring Freida Pinto — but also everything. … Of course, you might ask, at a time of such turbulence in the world, what do 19th century upper-class romantic machinations have to do with, well, anything? To which we say: Whatever! Bring it on. Distract us with your lovely frocks flowing straight from the bosom, your exquisite bonnets with feathers, your real-estate porn in the countryside and your smart dinner-table repartee. We could do a lot worse.”

For the New York Times, Amy Nicholson wrote, “The film is too soft at heart to condemn Julia as a manor-bred mean girl. (It might be more fun if it wasn’t.) The early sequences are spritzed with a whiff of pity for this society’s anxious would-be wives. The screenplay … seems to suggest that a marriage-minded society breeds shallow, superficial girls. … The counterargument is that most of the items on Malcolm’s list — be truthful, be charitable, read books — are reasonable. A more innovative period comedy could be made from his frustration trying to find these basics among the upper classes.”

For IndieWire, Kate Erbland wrote, “Jane Austen doesn’t hold the monopoly on Regency Era rom-coms, and nor should she. Jones and Allain’s vision of how we might reinterpret this sort of story for the big screen — including assembling a cast of people who are charming to watch, full stop — is both vital and delightful, and if it has some kinks to it, perhaps that’s just the price of trying something new. Mr. Malcolm learned the hard way that a prescribed list will never get him what he needs, perhaps this particular sub-genre of stories needs to discover the same thing.”

‘The Forgiven’

Written and directed by John Michael McDonagh, “The Forgiven” is adapted from the 2012 novel by Lawrence Osborne. In the film, unhappily married couple David and Jo (Ralph Fiennes and Jessica Chastain) are driving to a friend’s luxury weekend party in the remote desert of Morocco when they kill a young man with their car. What ensues is a stark examination of class, privilege and post-colonial attitudes. With a supporting cast including Matt Smith, Caleb Landry Jones, Christopher Abbott, Abbey Lee and Saïd Taghmaoui, the film is in theaters now.

For The Times, Robert Daniels wrote, “David and Jo’s verbally combative relationship adds to the barbed tone, but Fiennes and Chastain feel as though they’re acting in different movies. He’s a stiff-upper-lip Brit and she’s aping Monica Vitti in Michelangelo Antonioni’s ‘Red Desert.’ The two styles create a kind of friction, which work in tandem, but struggle to catch fire in scenes where they’re apart, particularly for recent Oscar winner Chastain. … While ‘The Forgiven’ isn’t concerned with making David a better person — rather to get him to fully grasp his guilt — McDonagh’s methods can’t distinguish the film from the long list of stories about white folks learning lessons at the expense of brown people. There may have been higher ideals in mind, but ‘The Forgiven’ fails to gracefully reach them.”

For the New York Times, Manohla Dargis wrote, “Mostly, though, it allows you to spend time with Fiennes, whose performance — in its intricate, complex play of emotions and in the push-pull of David’s contempt for himself and for everything else — says more about this world’s nihilism than all the brittle chatter. Fiennes peels David in layers, unraveling this man until you see his hollow interior.”

For the Guardian, Benjamin Lee wrote, “As the final act beckons, ‘The Forgiven’ is perhaps, frustratingly, not quite the sum of its many parts. While the wild tonal shift between drunken excess and hollowing grief can be well-balanced and contrasted, at other times it gives the film a niggling unevenness, not helped by a rather repetitive and plain score that intrudes upon certain scenes and robs them of emotion. The film’s strange scrappy indefinability is both its blessing and curse. We’re left with pieces, interesting on their own and sometimes together, but not quite enough to complete the puzzle.”

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.