An audacious debut in ‘Funny Pages’

- Share via

Hello! I’m Mark Olsen. Welcome to another edition of your regular field guide to a world of Only Good Movies.

Larry Clark tribute. This weekend, the UCLA Film and Television Archive, in partnership with Los Angeles Filmforum, will feature a tribute to filmmaker Larry Clark, a key figure in what became known as the L.A. Rebellion, an influential movement of Black filmmakers from the UCLA film school. The series begins Friday night with 1977’s “Passing Through,” widely praised as one of the best films about jazz ever made. Other titles include 1973’s “As Above, So Below” and 2002’s “Cutting Horse.”

Rolling Stones rarity. Over the years, the Rolling Stones have worked with an astonishing array of filmmakers, including the Maysles brothers and Charlotte Zwerin, Peter Whitehead, Hal Ashby and Martin Scorsese. But no collaboration was quite like the one with Robert Frank and Danny Seymour on 1972’s “C—sucker Blues,” which captured the sleaze, paranoia and euphoria of the band’s “Exile on Main Street” album and subsequent tour.

The film has long been locked up in legal complications and is rarely presented publicly, which makes Friday night’s shows from Mezzanine particularly exciting. Presented by author Rachel Kushner, this is the first time the film has screened in Los Angeles since Frank’s death in 2019. As we were sending out this week’s newsletter, there were still tickets available for the late show added after the earlier show sold out.

Academy salutes the Actors Studio. As a celebration of the 75th anniversary of the organization, the Academy Museum is having a series of screenings and conversations. On Sunday, Ellen Burstyn will be there for a talk after Martin Scorsese’s 1974 “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore.” Other events include Al Pacino in conversation after Sidney Lumet’s 1975 “Dog Day Afternoon” and Sally Field discussing Robert Benton’s 1984 “Places in the Heart.”

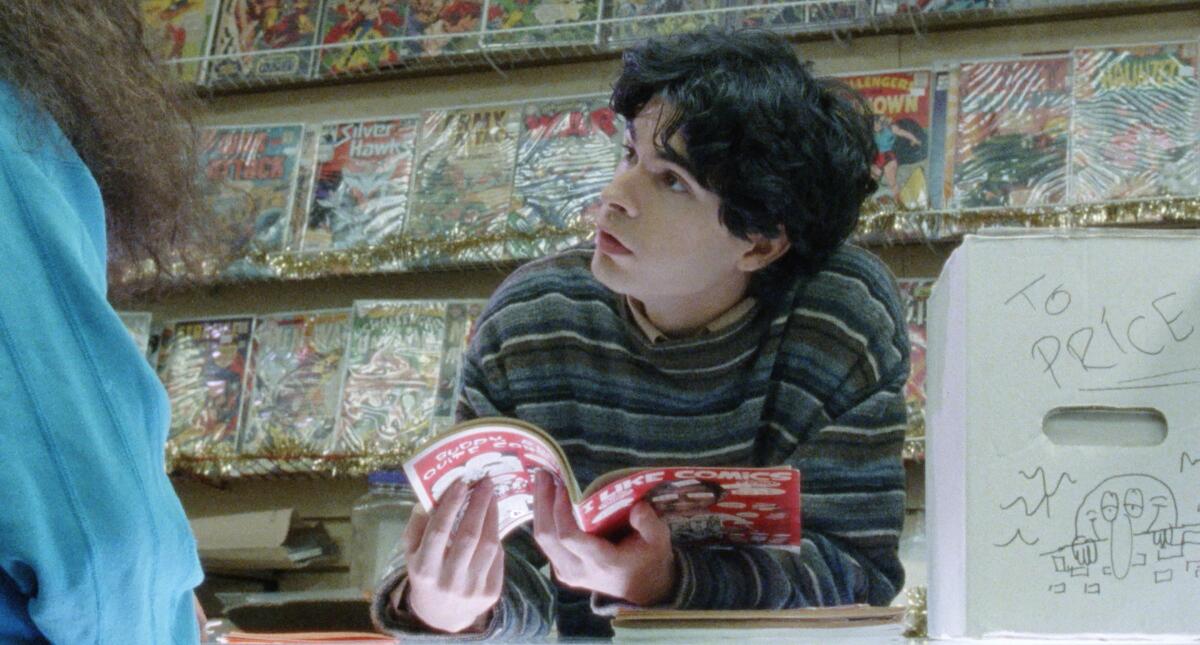

‘Funny Pages’

Owen Kline makes a very promising debut as writer and director with “Funny Pages.” Kline has been best known up to now for his role in Noah Baumbach’s “The Squid and the Whale.” (And for the fact his parents are Phoebe Cates and Kevin Kline.) The film is the story of Robert (Daniel Zolghadri), who wants to reject the suburban comforts of his upbringing for a grotty world as an aspiring underground cartoonist. Produced by the Safdie brothers and Ronald Bronstein, with cinematography by Sean Price Williams and Hunter Zimny, the film creates a unique, awkward world of its own. The film is now in theaters.

For The Times, Justin Chang wrote, “An attention-grabbing debut for its 30-year-old writer and director, Owen Kline, ‘Funny Pages’ draws its cranky-grungy energy from the 1970s heyday of underground comics and also from the rough-hewn independent films that proliferated during that period. … ‘Funny Pages’ itself sometimes feels like an exercise in misplaced artistry, a student’s overly precocious stab at brutish cynicism. Its biggest laughs, which tend to go hand-in-hand with its meanest jolts, seem to arise less from any recognizable emotional or situational reality than from a filmmaker’s desire to shock and humiliate his characters, to put them repeatedly through the wringer.”

For the New York Times, Manohla Dargis wrote, “Among the film’s virtues is that it’s exhilaratingly free of the do-gooder, aspirational current that runs through so many ostensibly independent features (unless you too aspire to Crumb-like artistry), and that effectively repackage the same Sunday school moralism the old-studio movies did. … There are fights, a car crash, some domestic drama, but mostly there is Robert in his own wonderland, a dank, clammy, sometimes sordid place of delight, baseness and naked feeling, one that’s far from the one inhabited by, say, the status-conscious music dudes in the film ‘High Fidelity.’ There’s nothing remotely cool about Robert or, really, ‘Funny Pages.’ That’s because cool is entirely beside the point. What matters is a sensibility, a worldview — what matters is art.”

For the New Yorker, Richard Brody wrote, “The movie is a comedy, filled with antic absurdities, exaggerated personalities, actorly caricatures, uneasy situations, jolting incongruities, and off-kilter dialogue — yet it also relies on its recognizable genre for dramatic shortcuts, turning the story into a series of sketches and set pieces that are less focused on character or experience than on making a point. … In effect, ‘Funny Pages,’ despite its winks toward the comic-book coming-of-age classic ‘Ghost World’ and the nerd-dialectical ‘High Fidelity,’ is above all an anti-‘Whiplash,’ a repudiation of the value of the young aspirant’s desperate dependence on a technically skilled but emotionally stunted veteran’s lessons and approval.”

For Vulture, Alison Willmore wrote, “While Kline’s affection for the oddballs he puts on screen feels genuine, there’s also a level of calculation to how he depicts them — unlike the Safdie brothers, who produced the film, and whose work hurls itself wholeheartedly into the peripheral communities in which it’s set, he can’t help but regard his characters at a self-aware remove, appreciating them as good material rather than people. ‘Funny Pages’ is a canny portrayal of a young man from a comfortable background going on a sojourn amid the outcasts, failures, and economically desperate, but you get a sense, by the end of the film, of Kline playing tourist himself.”

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

‘Three Thousand Years of Longing’

Directed by George Miller, who co-wrote the adaptation of a short story by A.S. Byatt, “Three Thousand Years of Longing” is a romantic fable that also has a keen interest in how and why stories are told. A narratologist named Alithea (Tilda Swinton), in Istanbul for a conference, finds herself in possession of a vase that contains a Djinn (Idris Elba), who tells her of his many adventures as he entreats her to make a wish of her own. The film is playing now in theaters.

For Tribune News Service, Katie Walsh wrote, “Miller’s vision is an earnest and high-minded one, with more insights about humanity and storytelling packed into a tossed-off moment than most entire films contain. But it’s also a deeply odd film, spanning centuries but contained to the interaction between Alithea and the Djinn. In line with core tenets of Miller’s genre-spanning work, it most clearly espouses the questions of human existence, human desire and how it’s desire that makes us human, whether for love or survival or both. … The only messages or lessons in ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing’ are to be gleaned ourselves from the clues left behind, which is a fascinating — if a bit frustrating — experience.”

I spoke to Miller about “Three Thousand Years” but also about his upcoming “Mad Max: Fury Road” prequel, “Furiosa.” Asked how he might define a George Miller film, he said, “When you are looking to make a film — I’m not saying this is what happens, but this is the aspiration — you’re looking to make a film that engages the whole of the human being. By that I mean it must work viscerally. It must get you in your gut. It must get you emotionally in your heart. It must get you in your mind and your intellect. It must get you in terms of the collective, the thing that you recognize in yourself as being part of some larger human experience, and we could call that the mythological or the spiritual. It must do all of that at the same time. That’s the hope.”

For the New York Times, Manohla Dargis wrote, “Despite these flashes of playfulness, the stories blur rather than build. They’re overlong, for one, and because Djinn often narrates their characters’ words, thoughts and deeds, they rarely come alive. Much like the figurines in old-fashioned automaton clocks, they enter at the appointed time, execute clever bits of business and exit, leaving no impression other than admiration for the clockmaker’s skill. Worse, they take you away from Alithea and Djinn. And while the last half-hour is lovely — it’s here that you see the movie, and feel the tenderness, that Miller himself clearly yearns to convey — by then, alas, the clock has almost run out.”

For the AP, Lindsey Bahr wrote, “There is not a cynical molecule in the makeup of George Miller’s ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing,’ a patient and occasionally dazzling fantasy about love, myth, hope, companionship and perhaps, most of all, about storytelling. … At times, you may grow impatient wondering what it’s all building towards and if you even care, as Alithea doubles down on her stance that she’d rather not make any wishes at all. But she, and the audience, are in for a surprise. It’s the kind of moment that doesn’t make a lot of emotional sense on paper, but that’s why we go to the movies, isn’t it? Swinton and Miller make it work.”

For Vulture, Bilge Ebiri wrote, “We may realize, if we haven’t already, that all the film’s tales have turned on images of captivity — from the Djinn’s imprisonment in the bottle, to the Ottoman sultans and their infamous golden cages, to the physical confinements of a forced, loveless marriage. Concurrent to all that, a spiritual and emotional entrapment runs through the picture as well — from the sweet hypnosis of a story that seems to have no end, to the idea of a love that cannot be given freely. ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing’ is indeed a cautionary tale, but it’s a complex, beautiful one, suggesting that love, longing, and loss are all parts of a vast, wondrous life.”

‘Breaking’

Directed by Abi Damaris Corbin from a screenplay written by Corbin and Kwame Kwei-Armah, “Breaking” is based on the true story of Brian Brown-Easley, a Marine Corps veteran who held up a bank for the $892 he was owed by the Department of Veterans Affairs. The movie stars John Boyega, and the cast also includes Nicole Beharie, Connie Britton and Michael K. Williams in one of his last roles. “Breaking” is in theaters now.

For The Times, Michael Ordoña wrote, “This isn’t a documentary and shouldn’t be held to exacting journalistic standards, but the lack of context and focus make ‘Breaking’ feel unmoored. It also doesn’t need to be some sort of thrill ride — but a deeper, grittier dive into its protagonist might have helped the film connect. The film doesn’t delve into the reasons for the missed payment to create something resembling an antagonist — whether that be VA bureaucracy, Brown-Easley’s mental instability or whatever. Rather, we have a protagonist with whom we vaguely sympathize because, apparently, he means no harm to others. … Brown-Easley’s story is interesting and the film’s acting is committed. Unfortunately, as a cinematic experience, ‘Breaking’ fails to compel.”

Back when the film debuted at Sundance (with its original title of “892),” Sonaiya Kelley spoke to Boyega and Corbin. Boyega spoke about meeting with Easley’s ex-wife, Jessica, before playing the role, saying, “There’s definitely an emotional weight playing somebody that has existed who has had to live a tragedy in order for you to play him. [Jessica] told me it felt like I captured Brian. She was real descriptive of the experience of taking it in. She said that this movie is a direct lineage to Brian’s legacy: Brian wanted the world to know what was going on, how much frustration this was for people who’ve sacrificed so much for their country. The story is really [about] the isolation and betrayal that comes with serving your country and then coming back home to no opportunity or true help.”

For the Hollywood Reporter, Lovia Gyarkye reviewed the film out of Sundance under its original title. Gyarkye wrote that the film “is a sensitive dramatization of how the 33-year-old father had run out of options when he walked into the bank that July morning. … Corbin’s film doesn’t focus much on the police mismanagement part of the story, which feels like a missed opportunity to sharpen our understanding of the degree to which the state failed Brian. Still the narrative as it stands is certainly worth watching. Not only does it offer a damning lesson about how the United States abandons its veterans, but it tries, with honesty and feeling, to honor a man who just wanted to survive.”

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.