The imaginative ‘Nimona’ and the joys of ‘Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed’

- Share via

‘Nimona’

The animated science-fiction/fantasy hybrid “Nimona” is based on cartoonist ND Stevenson’s graphic novel, adapted to the screen by co-directors Nick Bruno and Troy Quane, who follow Stevenson’s lead in foregrounding the comics’ LGBTQ+ themes. The title character (voiced by Chloë Grace Moretz) is a shape-shifter who presents herself most often as a young woman but can freely change form — into animals or other people — according to how she feels or what she needs. Nimona becomes a sidekick to Ballister Boldheart (Riz Ahmed), a fugitive knight who has been falsely accused of regicide, pitting him against his fellow knight and secret love, Ambrosius Goldenloin (Eugene Lee Yang).

Nimona aligns with the reluctant Ballister, mistakenly thinking he’s eager to tear down a militaristic society that fears “monsters” like her. But, in a switch from the book, it turns out Ballister still thinks of himself as a hero. So to get him to a place of destructive rage, Nimona first has to convince him that the world he once swore to protect can be narrow-minded and cruel. As they flee from the authorities, Nimona shows Ballister what she’s had to endure to survive — and explains how she’s learned to thrive in the margins.

Though “Nimona” makes a strong, clear sociopolitical point, it’s not really all that preachy. Bruno and Quane (and a team of writers led by Robert L. Baird and Lloyd Taylor) take their cues from the puckish wit and sense of adventure in Stevenson’s work, and they’ve made a fast-paced, action-packed movie, set in a place that combines futuristic technology and a medieval-style social order. “Nimona” is imaginative and boisterous, just like its main character — the kind of inspirational free spirit who gets a kick out of shocking and tormenting anyone who won’t just let her be who she is.

‘Nimona.’ PG, for violence and action, thematic elements, some language and rude humor. 1 hour, 41 minutes. Available on Netflix; also playing theatrically, Bay Theater, Pacific Palisades

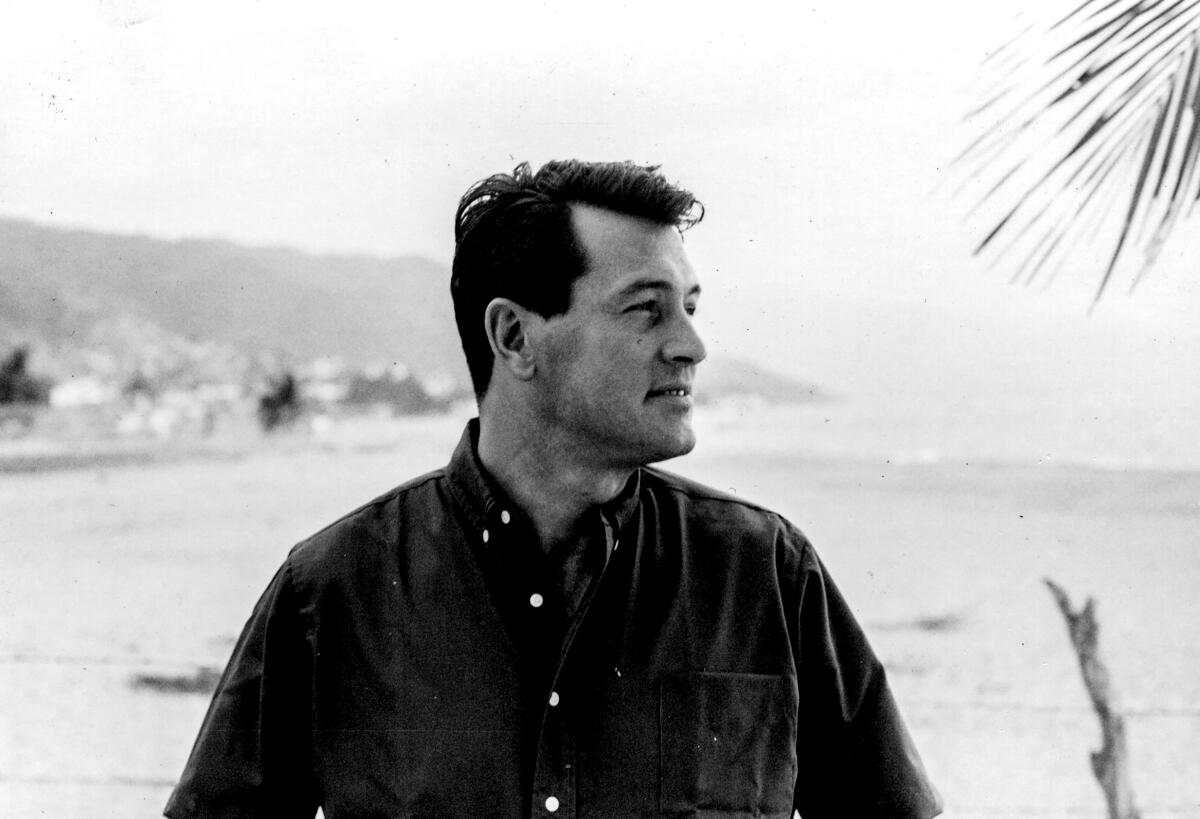

‘Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed’

Early in Stephen Kijak’s documentary “Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed,” we see a clip from the schmaltzy old 1950s TV show “This Is Your Life,” in which Hollywood superstar Rock Hudson — introduced under his prefame name, Roy Fitzgerald — is the guest of honor. Host Ralph Edwards promises to tell the audience everything they’ve ever wanted to know about the real Rock Hudson. Of course, these days we know there’s no way “This Is Your Life” could’ve told the whole truth about the actor, who was outed as gay when he died of AIDS-related complications in 1985.

“All That Heaven Allowed” is in some ways a straightforward biographical documentary, hitting the high points of Hudson’s career, from his commercial breakthrough in the florid Douglas Sirk/Ross Hunter melodramas of the 1950s and the Doris Day sex comedies of the 1960s to his towering performances in bigscreen classics like “Giant” and “Seconds.” But Kijak also gets into the pieces of Hudson’s personal life that were kept out of the press at the time — including his secret world of gay friends, boyfriends and parties in preliberation Hollywood.

Kijak’s film at times resembles Mark Rappaport’s groundbreaking 1992 cinematic essay “Rock Hudson’s Home Movies,” in that both use clips from Hudson’s films that ironically reflect his life in the closet. But “All That Heaven Allowed” also has extensive interviews with people who knew Hudson intimately, and who can explain how he coped remarkably well with the challenges of being gay in mid-20th century America. What makes this documentary a vital piece of Hollywood history is that it’s not as much about Hudson’s carefully managed public image as it is about the real joy and pleasure he experienced outside the spotlight — living not as some tortured romantic figure but as someone who savored whatever the shadows could provide.

‘Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed.’ TV-14, for language. 1 hour, 44 minutes. Available on Max

‘The Last Autumn’

The title of Yrsa Roca Fannberg’s documentary “The Last Autumn” refers to one final season of sheep-farming for an old Icelandic married couple, Úlfar and Oddný, whose kids have moved away and whose remote oceanside village of Árneshreppur has been getting more sparsely populated each year. Fannberg touches briefly on the various reasons for this decline, ranging from the increasingly harsh environmental conditions to general changes in the culture in Iceland; but because this film isn’t meant to be a cautionary tale or a call to action, Fannberg doesn’t dig deeply into what led these farmers to this point, or what they plan to do next. Instead, “The Last Autumn” mostly documents a way of life before it vanishes: the simple but nourishing meals, the hard manual labor, the neighborly pitching-in and the quiet hours looking out over ocean vistas like no other. Fannberg preserves all this on film as a place to keep visiting, long after it’s gone.

‘The Last Autumn.’ In Icelandic with subtitles. Not rated. 1 hour, 18 minutes. Available on VOD

Also on VOD

“Here. Is. Better.” could be superficially described as “a documentary about PTSD,” given that the bulk of the film consists of therapy sessions and slice-of-life scenes involving veterans who’ve had their lives disrupted by the persistent anxiety, guilt, sorrow, paranoia and edginess they’ve experienced since returning home. But by focusing on the cases of four specific men and women — including one well-known politician, Jason Kander — director Jack Youngelson goes beyond the broad clinical definitions and shows how this condition worms its way into ordinary tasks and interactions, posing challenges that can be hard even for those with PTSD to understand.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.