- Share via

When David Crosby recorded his first solo album, “If I Could Only Remember My Name,” in February 1971, he was, as the title suggests, lost and disoriented.

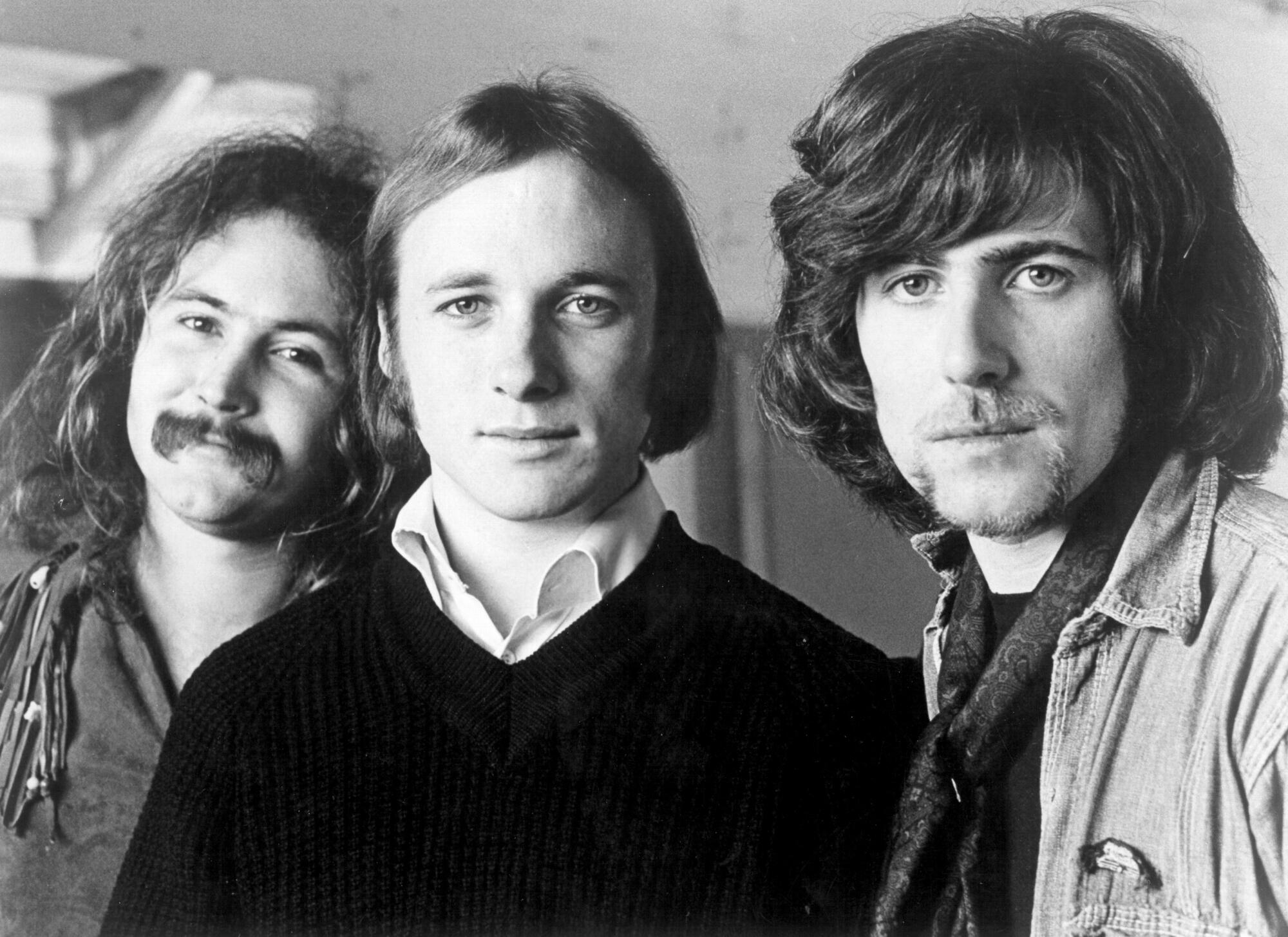

Made while Crosby, then 29, was living on his 59-foot sailboat, the Mayan, north of San Francisco, the album captured the moment Crosby’s monster success and wild-man lifestyle as a member of folk-rock supergroup Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young was upended by a personal tragedy that precipitated his descent into heroin addiction.

Largely panned by critics in its time, the record has taken on a cult status, hailed by younger critics and artists for its spooky, introverted folk-rock atmosphere, spacey improvisations and haunting harmonies by a cast of ’60s luminaries, including Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and members of the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane.

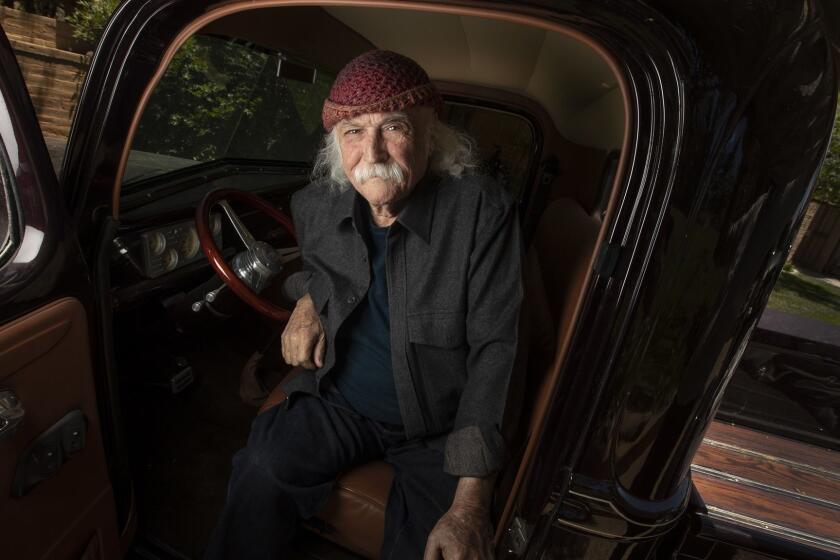

Crosby’s story of addiction, prison and recovery, his years-long interpersonal warfare with former bandmates and his arrests for drugs and firearms, is the stuff of legend, but suffice to say the singer-songwriter, now 79, remains feisty and stubbornly countercultural (he smoked pot during this entire interview from his ranch in Santa Ynez). An avid bomb thrower on Twitter, Crosby recently sparked outrage when he called singer-songwriter Phoebe Bridgers “pathetic” for smashing her guitar during a performance on “Saturday Night Live.”

“A lot of us do weird s— to get attention,” he says. “I get it. Only it’s dumb. She’s dumb to do it.”

“The United States vs. Billie Holiday” tells the tale of the FBI’s targeting of the jazz singer, whose “Strange Fruit” became a protest anthem.

Crosby has undergone a creative renaissance in recent years, producing four new albums since 2014, with a fifth, “For Free,” on the way. A candid assessment of his thorny life and times, “David Crosby: Remember My Name,” produced by Cameron Crowe, appeared in 2019. The pandemic, however, has made it impossible for Crosby to support himself with live performance and last month he became the latest legacy artist to sell his recorded music and publishing rights, striking a deal with Irving Azoff’s Iconic Artists Group for his solo work, as well as his work with the Byrds; Crosby, Stills & Nash; and CSNY.

Iconic will reissue “If I Could Only Remember My Name” later this year.

Describe what your life was like when you started recording this album in 1970.

I was living on my sailboat, in Sausalito, and the significant fact here is that my girlfriend, Christine [Hinton], had just got killed in a car wreck. I did not really have the equipment to deal with that. I had never lost anybody before, and it devastated me. And so I’m in the studio doing [CSNY’s] “Déjà Vu,” and this happens, and I barely make it through that record. And then I didn’t have any place that was safe for me to be. The only place that I felt like I could handle it was in the studio. I was trying to stay alive. It was that desperate. And there were these people, my friends. Paul Kantner, Grace Slick, Jerry Garcia. Good people. At that time, [Graham] Nash, too. And they came, Garcia particularly, almost every night, and worked on those songs with me.

Garcia figures prominently on the album.

Jerry Garcia was probably the single largest influence on [“If I Could Only Remember My Name”]. I don’t remember us talking about Christine, or the fact that I was sad or overwhelmed. But I know that he knew. He was sensitive and very intelligent, and he knew what I was going through. He showed up every night because he knew that that was going to save my f— life.

Like a musical therapist.

Yeah, because it was saving me. You know, it’s really strange, I tweeted this just the other day, I’m stunned by how happy [the album] sounds. It’s actually a pretty happy-sounding record, and I wasn’t. But music and friendship can help you transcend even deep sadness and loss. That album was a lifesaver, and I love it. I love it that Rolling Stone said it was a piece of crap.

Lester Bangs called it “a perfect aural aid to digestion when you’re having guests over for dinner.”

The truth is they just didn’t understand it. They were looking for another record that was full of big, flashy lead guitar and blues licks and screaming lyrics. It was not where everything else was going, so they thought it was irrelevant.

The album has been called “a stoner classic.” What kind of drugs were involved in the making of this album? Do you remember?

Yeah, I remember very well. I was in transition. I was coming from being a pothead for many years. I was in severe emotional distress, and in enormous pain. I had started doing cocaine, and I was doing a fair amount of it. And then I started doing heroin. But that was pretty much after the record got done. Yeah, that record was — the chemistry was still pot.

David Crosby knows he’s going to die soon. He’s diabetic.

On paper, the album seems like it could be a big mess, a bunch of stoners noodling, but it’s not that at all. The harmonies are disciplined and tight. Maybe it’s just because everybody involved were such pros…

No, it’s me, man. I’ll take credit for it. The harmony stacks are just me. There’s only a couple of songs where anybody else sings. All those stacks, they’re the Mormon Tabernacle Choir of me. The song at the end, “I’d Swear There Was Somebody Here.” That one is a triumph, man. I made that song in about 15 minutes. I was standing in Wally Heider’s [recording studio], using their beautiful echo chamber, a real live chamber, and I was just fooling with it. There’s six vocals there, and I did them one after another, two minutes each. And it’s probably the best piece of music I ever thought up. I certainly haven’t heard anybody else do anything even vaguely in that area, not one.

You used a similar vocal method on another track, “Tamalpais High (at Around 3).” What is a Tamalpais high?

When you’re going across the Golden Gate Bridge, Tamalpais is that big mountain right in front of you, in the middle of Marin County. And a Tamalpais high is going up on the mountain to look down at Stinson Beach and groove in the afternoon sunset. It’s also... I shouldn’t tell you this.

Go ahead.

Well, it also refers to Tamalpais High School.

What does that mean? That you were scoping high school girls from the top of the mountain or something?

I don’t think I should tell you! [Laughs] Oh, God. Of all the revealing answers.

Were you hanging out in the high school parking lot?

No, I didn’t exactly sit in the parking lot, but I did rip off one of their young maidens there. A girl that I dated was going to that high school and had just graduated.

Funny, the song doesn’t sound like it’s about dating high school girls.

“Tamalpais High” is more about being high on Mt. Tamalpais than it is the high school. I used to go up there a lot and cry. The place has great significance for me.

In the documentary, you told Cameron Crowe, “There are boundaries I crossed that you haven’t even thought of.”

Well, it was a different time. This was before the advent of AIDS, and after the invention of birth control, so … If you were adventuresome, there were adventures to be had. And I was adventuresome.

You had written a somewhat controversial song for the Byrds called “Triad,” about a threesome.

It’s not controversial, man. The French have been doing ménage à trois for centuries. It’s just unusual if you’re sexually very square. Lots of times, three people get together in a bed. I certainly wasn’t the only one doing it. It was fun to adventure back then. I continued being an adventurer for a long time, but my focus was really on obliterating [myself] with hard drugs. Once I got married to Jan [Dance, in 1987], I never touched another woman, ever, at all.

Everybody assumes these ménages were you and two women. Were there ever men?

Yes.

Anybody we know?

I’m not going to pull off anybody’s covers for you.

This album creates a serene, almost mystical atmosphere, but the lyrics to the song “Laughing” are about skepticism of mysticism. You sing, “I thought I met a man / Who said he knew a man / Who knew what was going on,” but then confess, “I was mistaken…”

It’s the George Harrison story. I went to England and in the course of us meeting the Beatles, I became friends with George. He was a very nice cat, very open, a very decent human being. Invited me over to his house for dinner, that kind of thing. Hung out with us. Later on, he tells me that he’s gone to India and met this teacher, this guru. George is smitten by him. I listened to what he was saying and I wanted to say to George, “That’s great, but take it with a grain of salt,” because usually when somebody comes on that strong that they’ve got the answer, it’s bulls—. I wanted to say, “Have some skepticism.” But I was too chicken to do it, because I had too much respect for George. So I wrote him that song. “I thought I met a man who knew a man who knew what was going on.” And I ended it by saying, listen, I don’t think he does know what’s going on. I don’t even know if George ever heard the song.

One of the delights of “Laughing” is hearing Joni Mitchell’s voice so distinctly in the group harmonies.

There’s a lot you guys don’t know about Joni. She’s always competing in a situation like that, and so she’ll find a way to stand out. She did, and it was stunning.

Was Joni somebody you could confide in during your sadness over Christine’s death?

Well, Joni still wanted to be my friend, but she had been my girlfriend. Then I fell for Christine, and Joni was very resentful of that. But same thing that I did to her, Joni did to everybody else. You have to remember, she was working her way through a long list of singer-songwriters. She had a thing: She wanted to score somebody, and she’d score them and then go around in public with them, and then ditch them. That happened over and over again. I don’t think she was happy then, I don’t think she’s happy now. But that’s neither here nor there.

In 1971, all the members of CSNY were making solo albums, including Neil Young’s “Harvest.” Was it competitive between you guys?

There was competition between us all the time, forever. Every minute of every day that we were together. We were always competing with each other, particularly Neil and Stephen, which made for fireworks.

Fifty years later, very few of the people on this album are on speaking terms.

The only one that I’m talking to is Stephen Stills. He and I are still friends. I haven’t spoken to Neil or Nash in a couple of years. Both of them have been most unkind to me, so I have no urge to.

What about Joni?

I had dinner with Joni at her place a couple months back, and it was wonderful and distressing. It was wonderful to reconnect and say hi, and I love her. I will always love her for her work. She’s the best singer-songwriter of her time. She’s as good a poet as Bob [Dylan], and she’s 10 times the musician Bob is. It was distressing to see her in the state that she is in now. She has trouble walking. And she’s having to relearn how to do stuff, physically. I don’t think that she will ever regain the manual dexterity to be able to play guitar or piano. She is trying to recover her skills as a painter, and she’s as good a painter as she is a guitar player.

Meanwhile, the reading public wants to know what your beef is with Phoebe Bridgers smashing her guitar on “Saturday Night Live.”

I don’t even know who Phoebe Bridgers is. She went to school with my granddaughter. I’ve never listened to her music. I wasn’t passing judgment on her at all. What I was objecting to is dramatics on stage. It bothered me when the Who did it. It bothered me when Hendrix lit his guitar on fire. It bothered me when Ozzy bit the head off of a bat. It’s showmanship at a very dumb level. Smashing your guitar has nothing to do with music. It’s childish. They said to me, “You’re saying that because she’s a girl.” Bulls—. I produced Joni Mitchell. Screw you. I treasured good girl songwriters.

The last time I interviewed you, I praised “If I Could Only Remember My Name” and you replied, “My next album’s going to be better.”

I frankly think these records that I’m doing now, they’re as good as “If I Could Only Remember My Name.” They are at that level of songwriting and expertise. As I said, the four of us [in CSNY] were always competing. Well, we still are. And I think I’m winning.

Joe Hagan is a special correspondent for Vanity Fair and the author of “Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.