- Share via

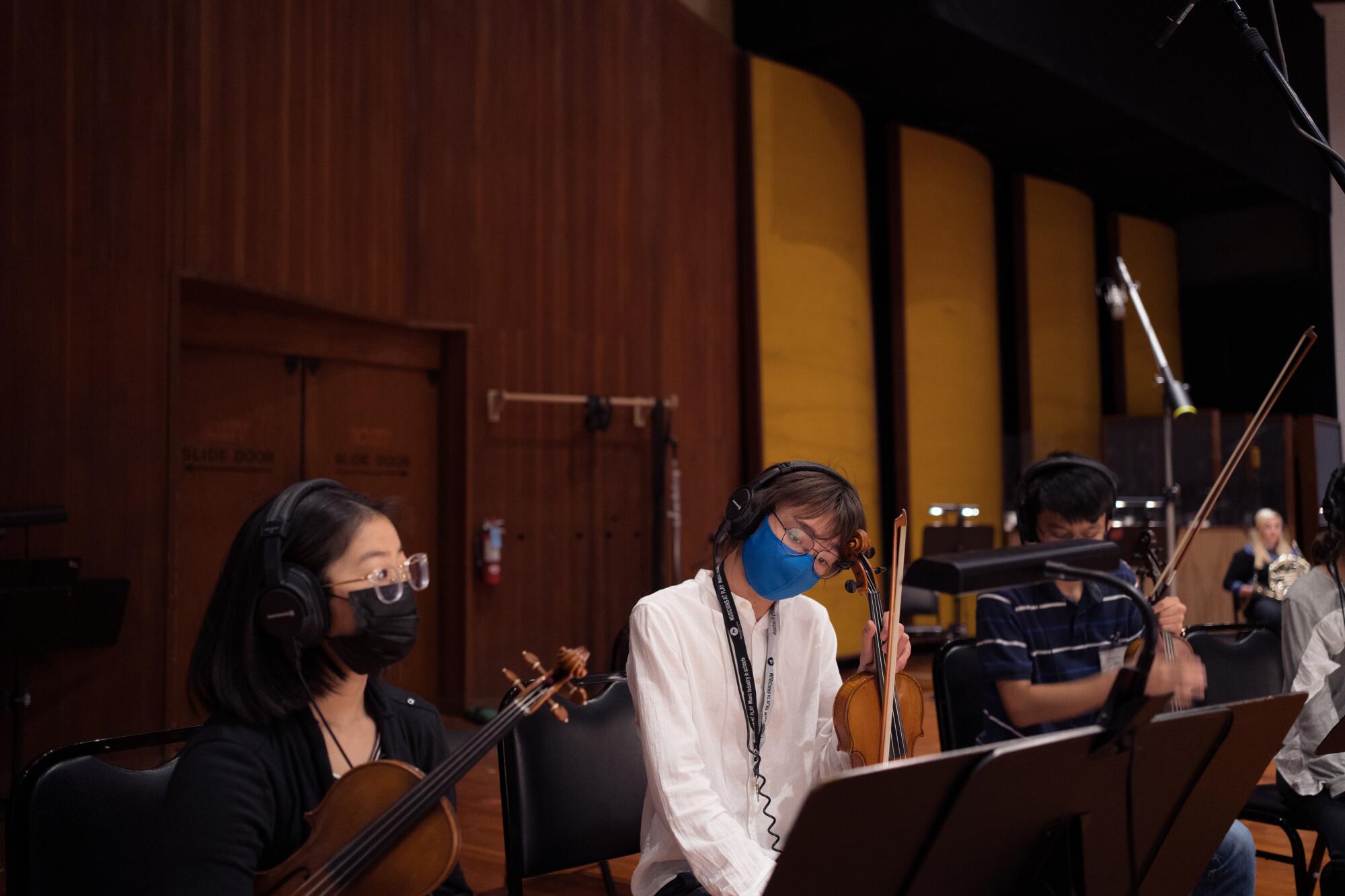

On a Sunday morning in May, the sound-locked wooden hull of the Warner Bros. scoring stage, where countless film and TV scores have been recorded since the days of “Casablanca,” hummed with energy. Musicians tuned their strings and did scales on their wind and brass instruments, ready for the downbeat of the conductor’s baton and the red “recording” light to flicker on. Hands were poised for action on cello bows and French horn valves, waiting to begin laying down a piece of music from a major Pixar film. When the conductor launched the orchestra into the French-influenced ballad by Michael Giacchino, there were no sour notes.

None of this would be exceptional for an orchestra accustomed to recording Hollywood film scores — but these musicians were teenagers from high schools in the Los Angeles area.

“How many of you have played to click before?” Booker White, who had done the new arrangements of the music these students were recording that day, asked the group. A handful of hands went up in the air. “A few, OK. Well, let me give you a little history of click...”

White, the head of music preparation at Disney, explained that “Looney Tunes” composer Carl Stalling devised the “click track” — a metronome-like beat played through headphones — to help musicians synchronize with early cartoons in this very room. Fernando Arroyo, a professional violinist from Mexico also present for the session, encouraged the young musicians to listen to the click in one ear, but leave the other ear free to hear their fellow players.

When the constant tick-ticking started up as they recorded their first piece, the players took to it like ducks to water.

White and Arroyo were two of several film music veterans volunteering their time for the workshop and ensuring this session simulator felt as close to the real thing as possible.

The final cue of the three-hour session, from “Pirates of the Caribbean,” wasn’t one the students had rehearsed the day before — throwing the novice players into the deep end of sight-reading a piece for the first time. Their pitch was a little wobblier, their harmony a little less tight, but the music sounded solid for a surprise read-through.

“I don’t know how to explain it, but you can hear everything — including yourself — really well,” said Nicholas Doan, a 16-year-old bass player from Long Beach, during a break. “So you have to really listen to your intonation and make sure that you’re in tune with everyone.”

“It’s definitely a bit scary,” he added, “but I think it’s a nice experience, too.”

Students ranging from age 13 to 18 auditioned for this inaugural event of the Rise Diversity Project, which capped a week of Zoom workshops and a full day of rehearsals before the scoring session. Hailing from Asian, Latinx and Black communities, the young musicians traveled from Long Beach, Diamond Bar and Glendale to the soundstage in Burbank. The Rise project was conceived and organized by Musicians at Play, a nonprofit founded in 2015 by April Williams and her husband, Don.

Williams is the daughter of the late Maurice Harris, who played trumpet on Johnny Carson’s “Tonight Show” and on numerous film and TV soundtracks including “Bonanza” and “Rocky.” She grew up around these musicians, many of whom often go uncredited yet breathe life into movies. After mingling with many of L.A.’s incredible studio players every night at Vitello’s Italian Restaurant in Studio City — where she ran the jazz program for several years — Williams decided to start an organization that would expose these talented musicians to a broader audience while simultaneously providing music education to local schools in Burbank. The program later expanded to include institutions across the Southland.

For this event, Musicians at Play reached out to school music departments from Inglewood and other predominantly Black neighborhoods — but only a small percentage of the final orchestra was Black. Williams quickly realized that most of the Title I schools don’t have music programs, and one of the ways she hopes to increase the diversity project’s reach going forward is by sending more instruments and teachers into schools.

The organization ultimately aims to expose “audiences to L.A.’s musical cultural heritage,” she said. “And then when we’re in the schools, we pair it up with: where did this music come from? And the mentors talk about their experiences in the streets and in the world. We try to sync it up with our students and where they’re from so that they can relate to the music and see that their cultural heritage, musically, is in the film music and in music in general.”

One of those mentors is Don Williams, a timpani player and veteran of the scoring stage — and younger brother of composer John Williams.

“I just do the grunt work, really,” said April, “but he is definitely in charge of all the artistic and music. If it wasn’t for him, we wouldn’t have an organization.”

At the session, Don sat at his drums between two young percussionists. While running through the house-floating cue from Pixar’s “Up,” he told the player on his left that the glockenspiel can be a little louder and to try adding a little shimmer. After a seamlessly executed cymbal swell from the musician on his right, Don nodded and gave a thumbs up.

In each section, a mentor who knew the ropes of the film scoring business led the students through each performance and illuminated what their own experience in the industry has been like. Karl Vincent, a bass player and former touring musician, told the students that as soon as he discovered Hollywood scoring sessions he felt like he was home.

“The musicians who perform [film] music have been anonymous for a long time,” he told me later, “and we’re trying to change that. And also, young people coming up — even if they did know it existed — did not have access to it as a profession.”

“There’s talent everywhere,” he continued, “and we need to tap into all the talent everywhere. In the past, it was very exclusive. And that has to change. That has not helped the industry.”

The scoring stage is its own miniature musical universe, with unique rules and demands. Lightning-fast sight reading skills are paramount, the pressure is high when you’re recording music for multi-million dollar studio movies, and the click is ticking in everyone’s headphones.

“It’s so niche, and there’s so much institutional knowledge here,” said mentor Danielle Ondarza, a French horn player who’s been playing sessions for 23 years. Ondarza remembers being the only female in the brass section on most sessions when she first started.

“In the recording industry, we don’t audition for this — we just get called,” she said. “One of the problems is the pool of people who get called has not been diverse, and so it’s one of those chicken/egg things. ... If you don’t have any experience, you’re really not appropriate for the job. But you can’t get experience unless you get called for the job.”

At the end of the three-hour session, conductor Olivia Tsui praised the group — “From the first note we played yesterday morning till right now, is just a huge improvement,” she said — and she invited the players to listen to the playback of their day’s work, the recording of which they got to keep as a memento. The players all crowded into the recording booth and many of them pulled out their phones to take photos and video of the listening party. Even behind masks, their pride was radiant.

This was an instructive first attempt for Musicians at Play. April Williams plans to implement it earlier in the school year next time around so that students have more free time in their schedule, and to cast the net even wider. There are even talks to do it twice a year, she said: “You know, everybody dreams big.”

Ondarza believes it’s possible the Rise project can contribute to broadening who we hear on soundtracks as well. “Experiences like this put it out there in the world for young people: I want to do this, I can do this, I have done this,” she said. “And it just changes your whole trajectory. It changes the way you interact with your instructors. It changes the kind of music you listen to. It changes your approach. And I have to believe that will lead to more diversity.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.