In a new exhibit, Wayne Thom’s photographs examine buildings as ‘functional sculptures’

- Share via

Upon entering the USC Pacific Asia Museum, you’re met with the most unwieldy contraption of a camera, a Sinar 4x5 C-series, once helmed by a man who documented one of the most iconic periods of architecture in California.

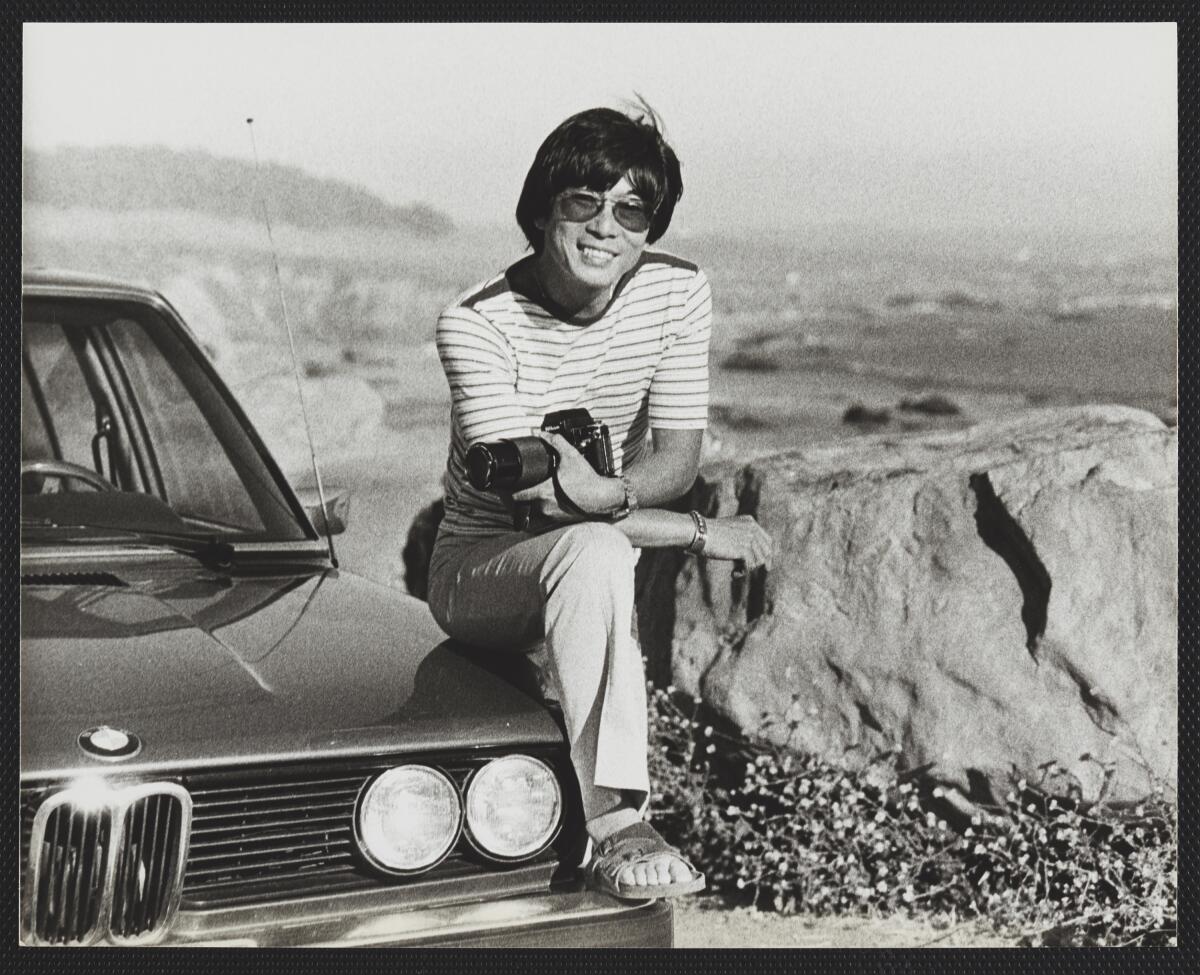

He’s to the right, sporting an aptly ’70s haircut and picturesque smile, with one foot resting on the bumper of a car and a camera in hand. He is Wayne Thom, architecture photographer. Well, at least that’s what he used to be.

Thom retired in 2015. However, at the age of 89, his work is being remembered with “After Modernism: Through the Lens of Wayne Thom,” an exhibition dedicated to his work from a key era of 20th century architecture as Los Angeles established itself as a culture capital.

While visitors can swipe through 50 projects that span 50 years of Thom’s career through an interactive archive booth at the exhibit, “After Modernism” also features more than 75 photographs and archival materials from USC Libraries’ Wayne Thom Photography Collection, a 250,000-image trove, which the university acquired in 2015.

The exhibit’s curator let the collection inform her curatorial focus, which led to a correlation between Thom’s most prolific years and the early 2020s. “This decade we’re in right now marks the 50th anniversary of the 1970s, which is the period Late Modernism is really coming to the fore,” says Emily Bills, architecture historian and the exhibit’s curator.

Between the end of World War II and the 1960s, Modernism in architecture responded to the public need for basic functionality with rationality, stronger materials and a simplistic geometry.

The late 1960s is the story of L.A. turning vertical, an intrepid response to the lifting of a municipal height ordinance that forbade the construction of buildings more than 13 stories or 150 feet high in 1956. More often than not, you’ll find the words “Late Modernism” and “exaggeration” in the same sentence. Late Modernism enters the new decade with the intention to stand out.

The first room celebrates some of Thom’s earliest works of the late 1960s, which were commissioned by former dean of USC School of Architecture and “a doyen of California Modernism,” A. Quincy Jones. Thom was given the task of photographing a handful of Jones’ buildings, one of them being the Congregational Church of Northridge, an eccentric site of worship with depressed sanctuary floors and screen walls lying within a pyramid-like structure on a triangular plot of land.

Bills said Thom laid on his back with the delicate Swiss-made Sinar in this relatively dark sanctuary interior to capture light coming in through the skylight at the pyramid’s point, just without a brilliant flare. Jones, impressed by the photographer’s eye for contrasting natural light and perspective in a portfolio of his architecture, introduced Thom to several design directors at California firms — a major turning point in his career.

In the next room, Thom’s portrait of William L. Pereira and Associates’ Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco demonstrates a growing audacity. One shot, from an elevated perspective, is the entire white high-rise against a medley of blues in the horizon, and another is from the pyramid’s base — a closer inspection of the complex geometric fortification working with natural light.

The meticulous development process of these photos comes down to photochemistry, the marriage between light and science.

“He understood how a camera works,” Bills says. “But Wayne considers the developing process the heart of photography as an art.”

“Mirror glass building is a nonexistent building,” Thom asserts in one of the exhibit’s video clips. The inherent form doesn’t represent a building, but rather its surroundings. His ingenuity is arguably best represented in his shot of Langdon and Wilson’s CNA Park Place Tower, now the Los Angeles Superior Court building. Known as one of the first all-mirror glass buildings in the world, the tower was first photographed by Thom.

His methodical approach to photographing something as tricky as all-mirror glass without the harsh impact of the sun projected a softer display of light on the reflection of overcast clouds on the tower. Upon further inspection of the bottom right corner, a man can be spotted tending to pigeons, a moment of dramatic resonance that transcends human engineering.

“It’s a form of art,” Bills says. “No photograph is an exact replica of something in the world. It’s a reflection of the photographer’s experience, their vision.”

The curator says that Thom often began at the architect’s office, learning about the engineering of the facade, the materials used, and the building’s relationship with its landscape. It all led to one question: How could Thom present this high-rise as a “functional sculpture”?

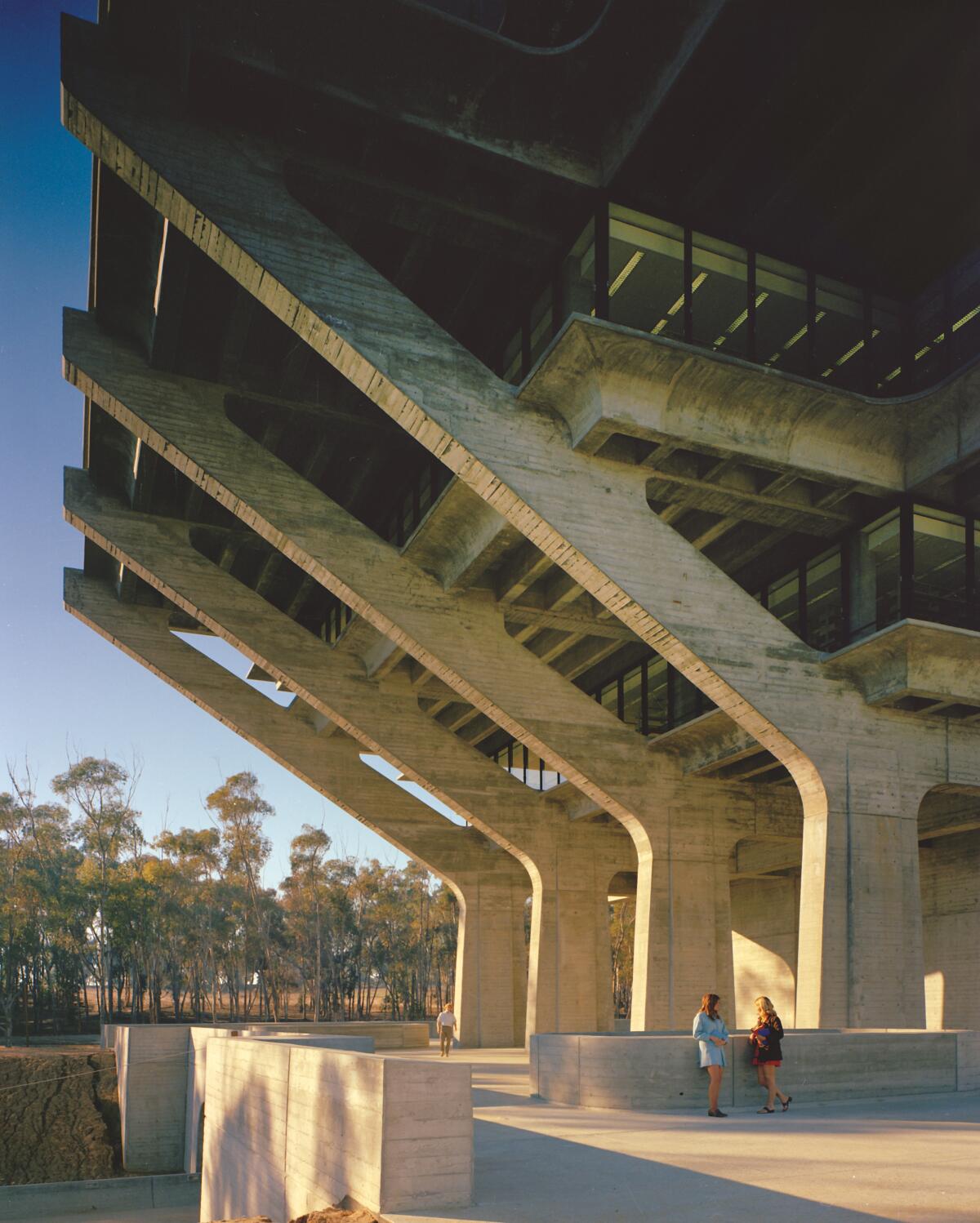

In concrete-clad fashion, UC San Diego’s Geisel Library is a dramatic conclusion to the exhibition. Designed by Pereira and Associates, the building is like something out of Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange,” commanding your attention with a confidently protruding silhouette within Thom’s frame. The library nearly resembles the shape of a brain, with the entrance being the medulla oblongata and the robust flooring as the cerebellum.

“There are three very large photographs of [the Geisel Library] side by side for a reason — I know those have an impact,” Bills says. “Everybody talks about [how] ‘brutalism is so bad,’ but there’s a really lyrical quality to how that building was designed, and I describe it as like a pyramid that was thrown up in the air and flipped over and landed on the ground. How fun is that!”

Before Thom found himself bribing his way onto scaffoldings and hopping in helicopters to get his high-rise shots, he was turning the family bathroom into a darkroom on weekends after his aunt gave him his first camera, a Japanese-produced Mamiya Six. Born in Shanghai and raised in Hong Kong, Thom eventually migrated to Vancouver, Canada before attending Brooks Institute of Photography in Santa Barbara in the mid-1960s for a more technical rather than theoretical approach to photography.

“When Wayne first became a professional, he was working for a lot of big firms in Los Angeles who were changing the way Southern California looked,” Bills says. “The time period, historically, is also quite significant in terms of transitioning urban landscapes.”

While the exhibit commemorates the serpentine arches of the Arena at the Anaheim Convention Center, the way natural light illuminates the surface of the Bonaventure Hotel interior’s soft edges, and the Walt Disney Concert Hall adorned by a crescendo of steel — and other Late Modern works throughout the western United States — the combined efforts of everyone involved presents a larger conversation.

“There’s also a historic preservation angle to the exhibition, to the book, and to my work with Wayne,” Bills said. “Buildings from this time period are just starting to hit their stride in terms of popular appreciation. Typically in historic preservation, buildings are considered ‘historical’ when they hit the 50-year mark.”

The guideline was established by National Park Service historians in 1948. “While there is no age limit in Los Angeles for local landmark designation, the 50-year rule remains a benchmark for examining buildings and structures from a period not yet long-gone,” according to the Los Angeles Conservancy.

Along with the increasing deterioration of materials from a half-century ago, the Conservancy ascribes the impending loss of the city’s late modern architecture to the lack of affinity for the aesthetics of the time. In 2020, Los Angeles County Museum of Art began demolishing three Pereira-designed buildings, which were polarizing even when they were built in 1965.

“A lot of people don’t know that [Thom] was often behind the lens and taking those photographs that became really quietly iconic,” says USC Roski School of Art and Design professor Jenny Lin. “They’re much more than simple illustrations of the buildings themselves. It relates back to the way in which he almost orchestrated these performances in order to capture these buildings at their best — kind of daringly get these shots that a lot of other people just wouldn’t have thought about having that perspective of a building.”

After Modernism: Through the Lens of Wayne Thom

Where: USC Pacific Asia Museum, 46 North Los Robles Avenue, Pasadena.

When: Wednesdays – Sundays: 11-5 PM. Closed on Mondays and Tuesdays

Info: info@pam.usc.edu, 626-787-2680

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.