The Fountain’s ‘Heart Song’ gives voice to flamenco’s depths

- Share via

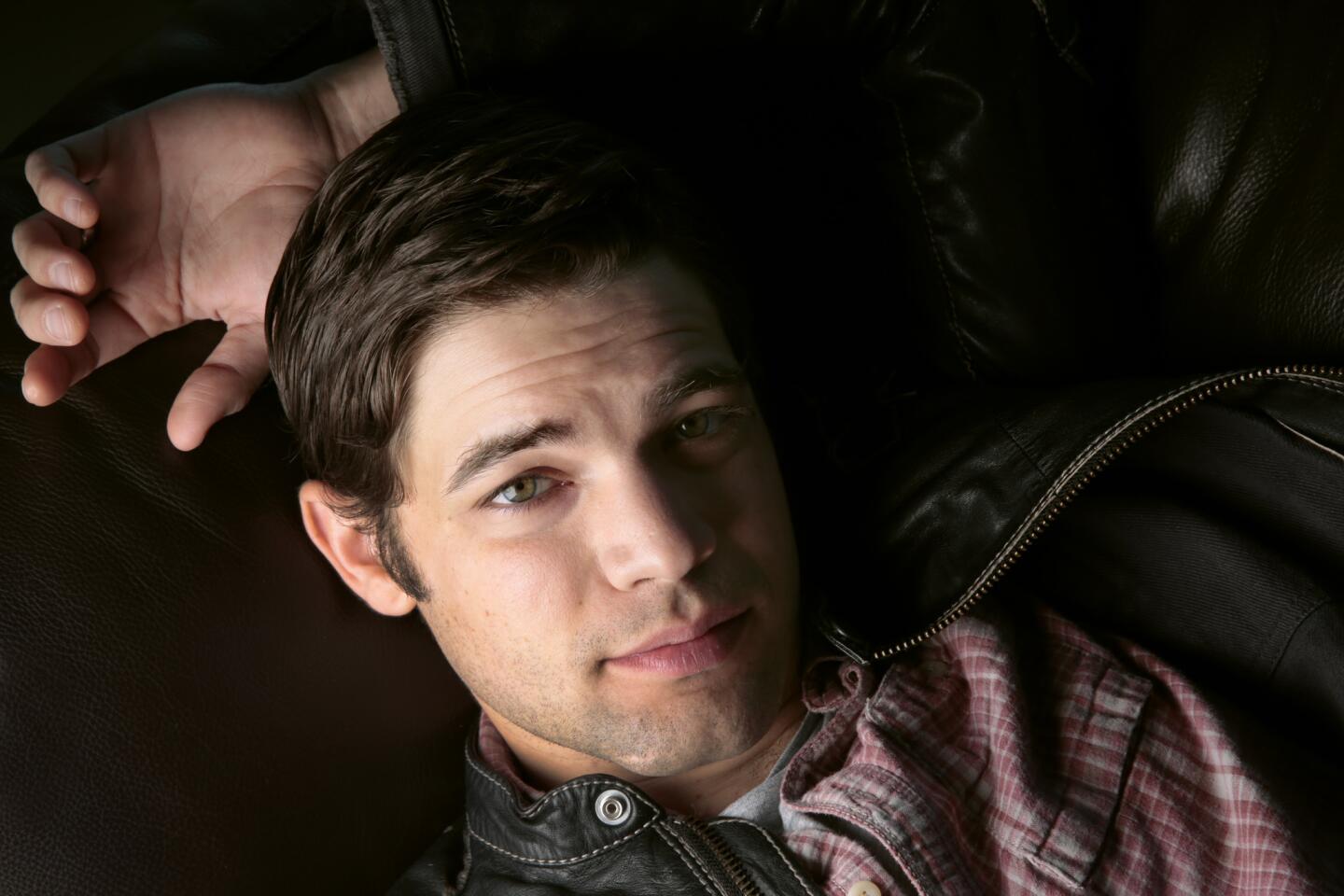

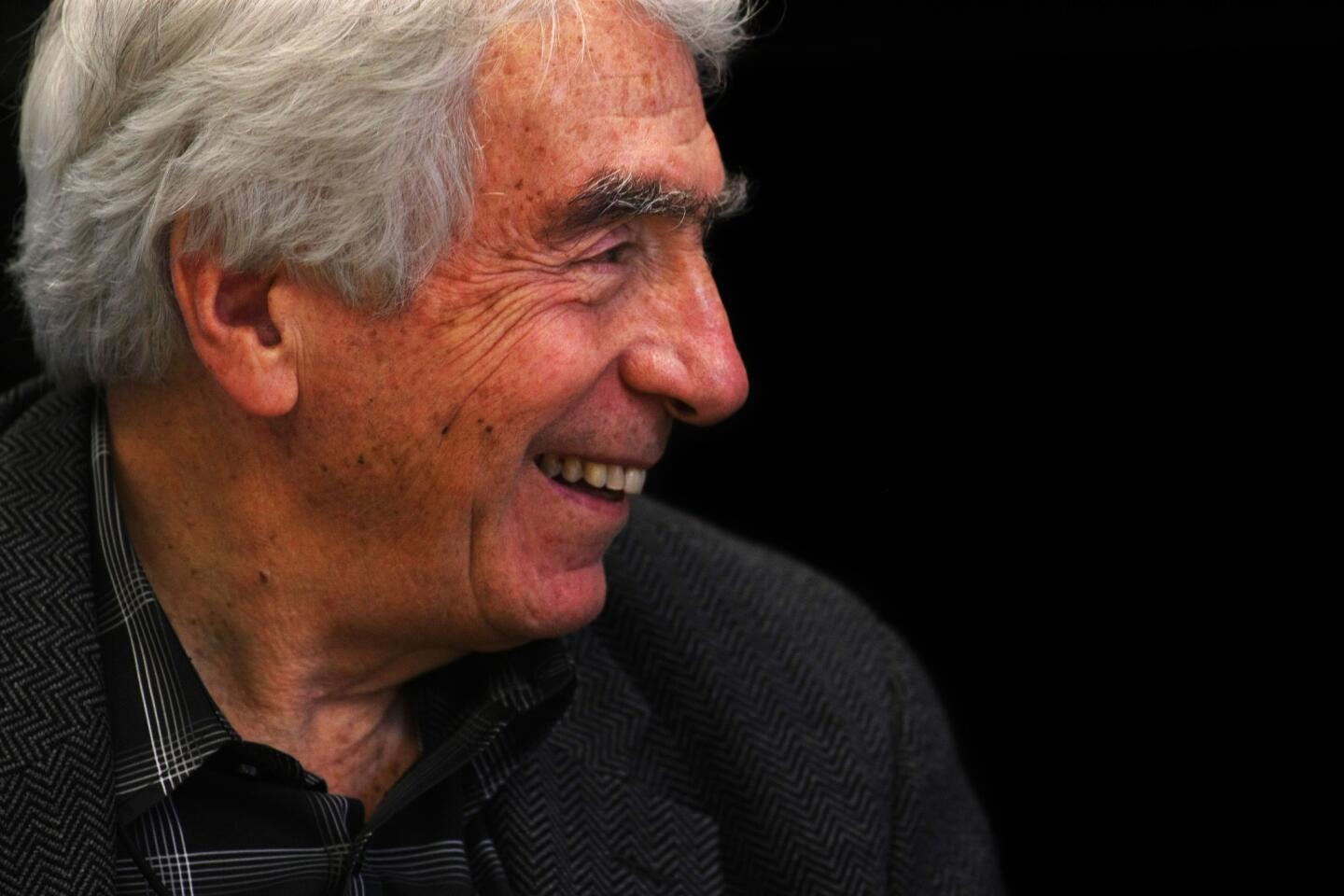

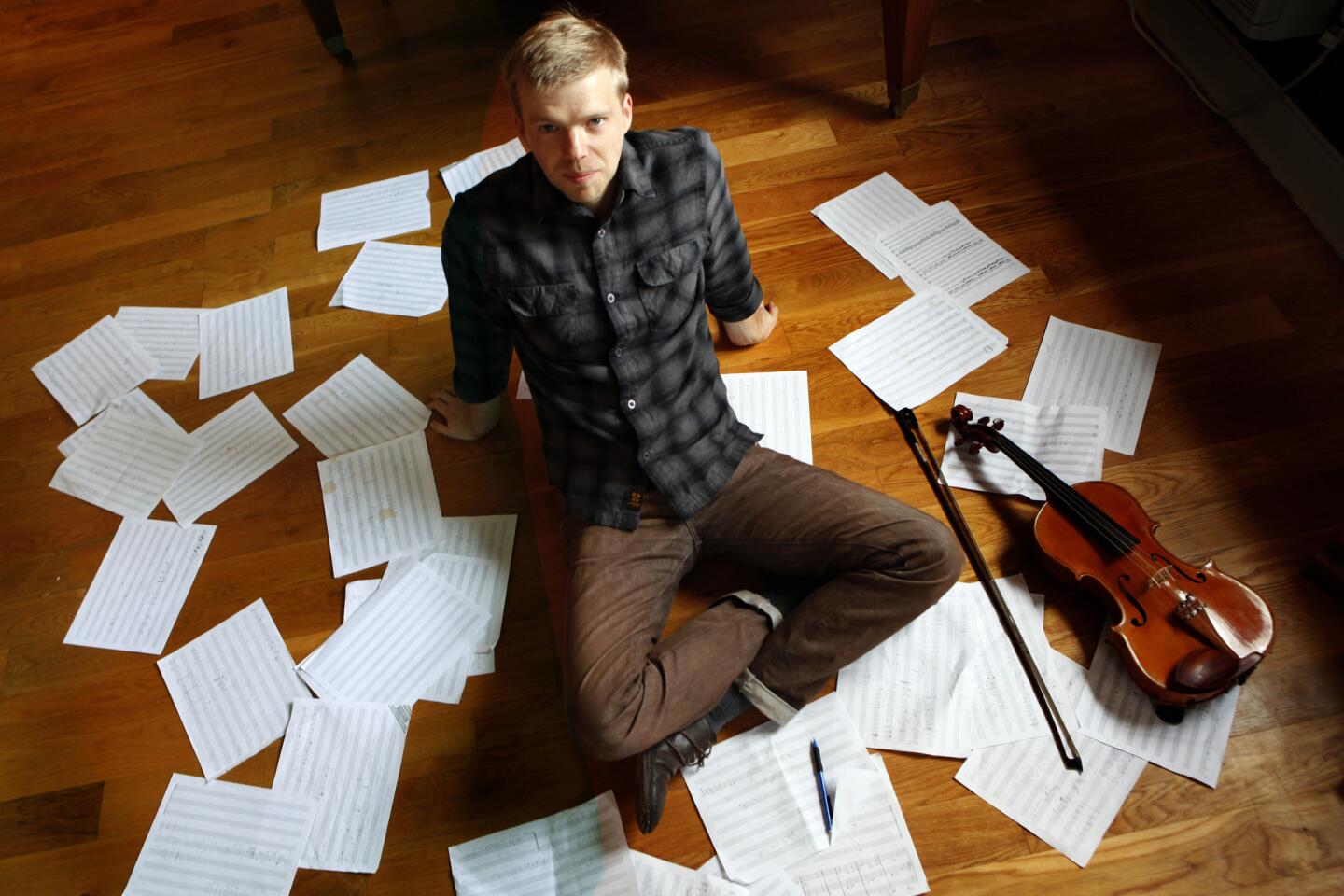

Two years ago Stephen Sachs began working on a play about the philosophy and practice of flamenco. He figured he had all the material he needed, having spent years in close proximity to flamenco dancers as the co-artistic director of the Fountain Theatre, home of the long-running performance series “Forever Flamenco!” But after further research, he realized that the Spanish art form intertwined deeply with certain existential preoccupations that also inhabited his writer’s mind.

“The older I get, the more aware I have become of the loss of loved ones, the time in front of me and how I’m spending it. You start to wrestle more with these things,” observes the 53-year-old playwright and director.

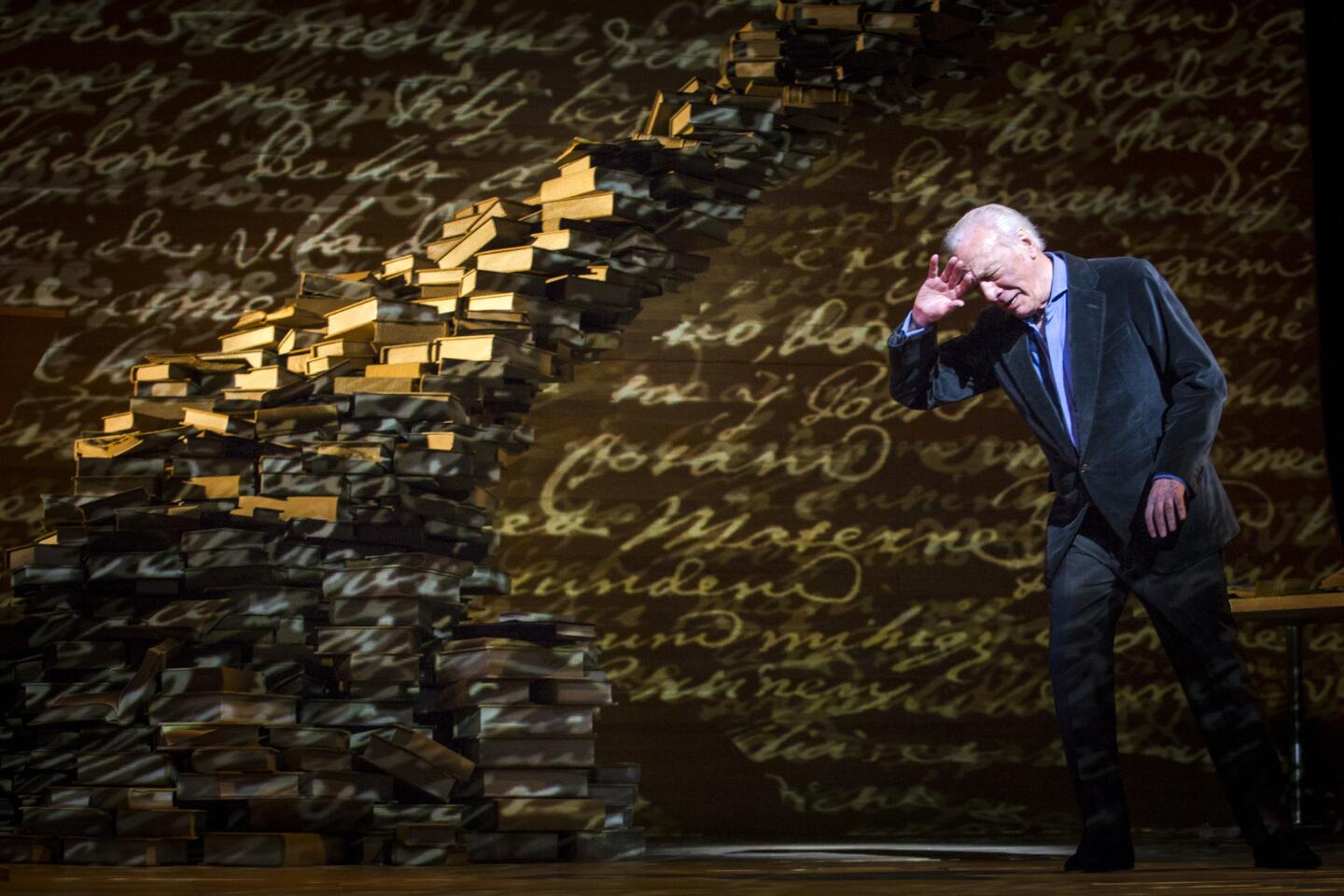

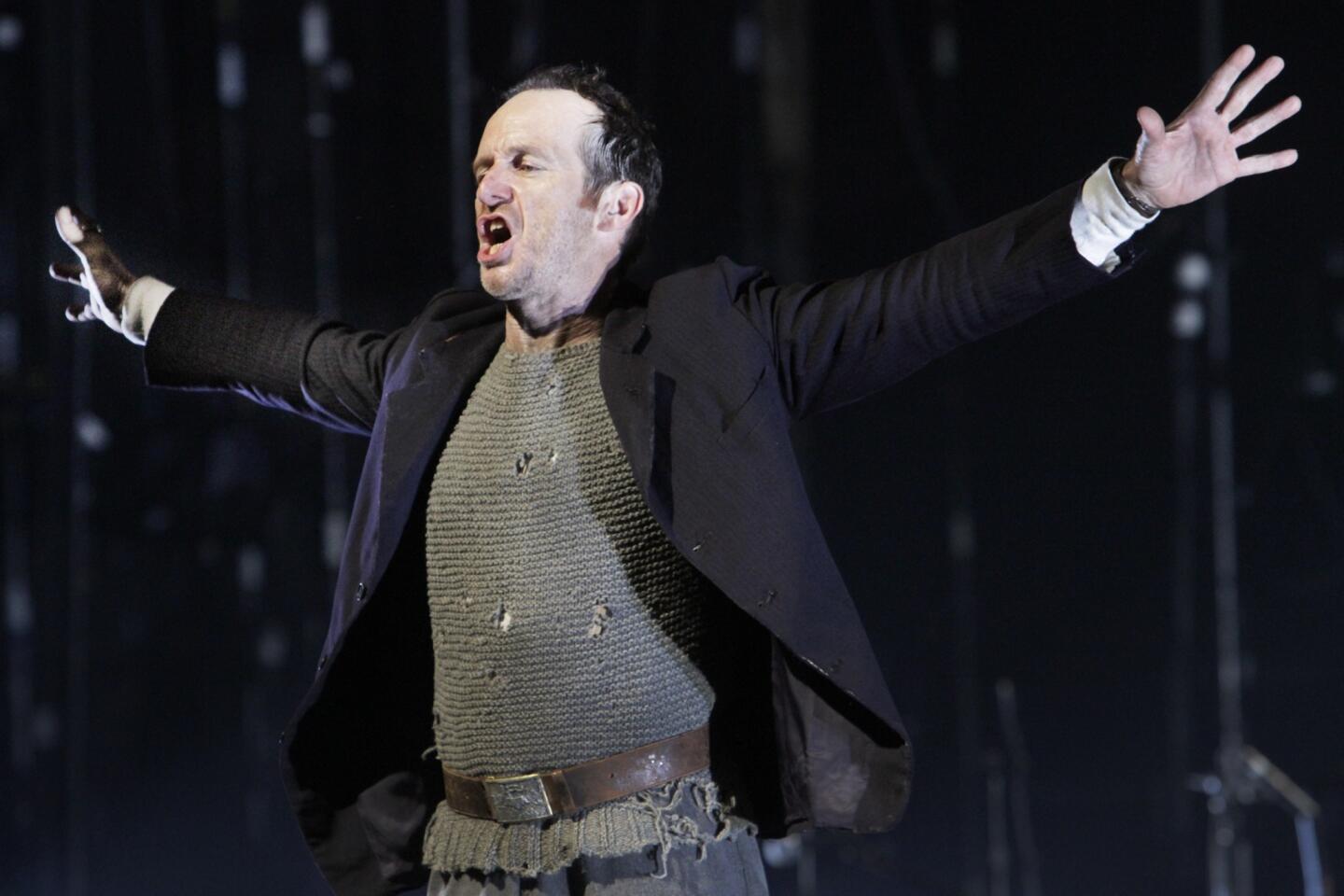

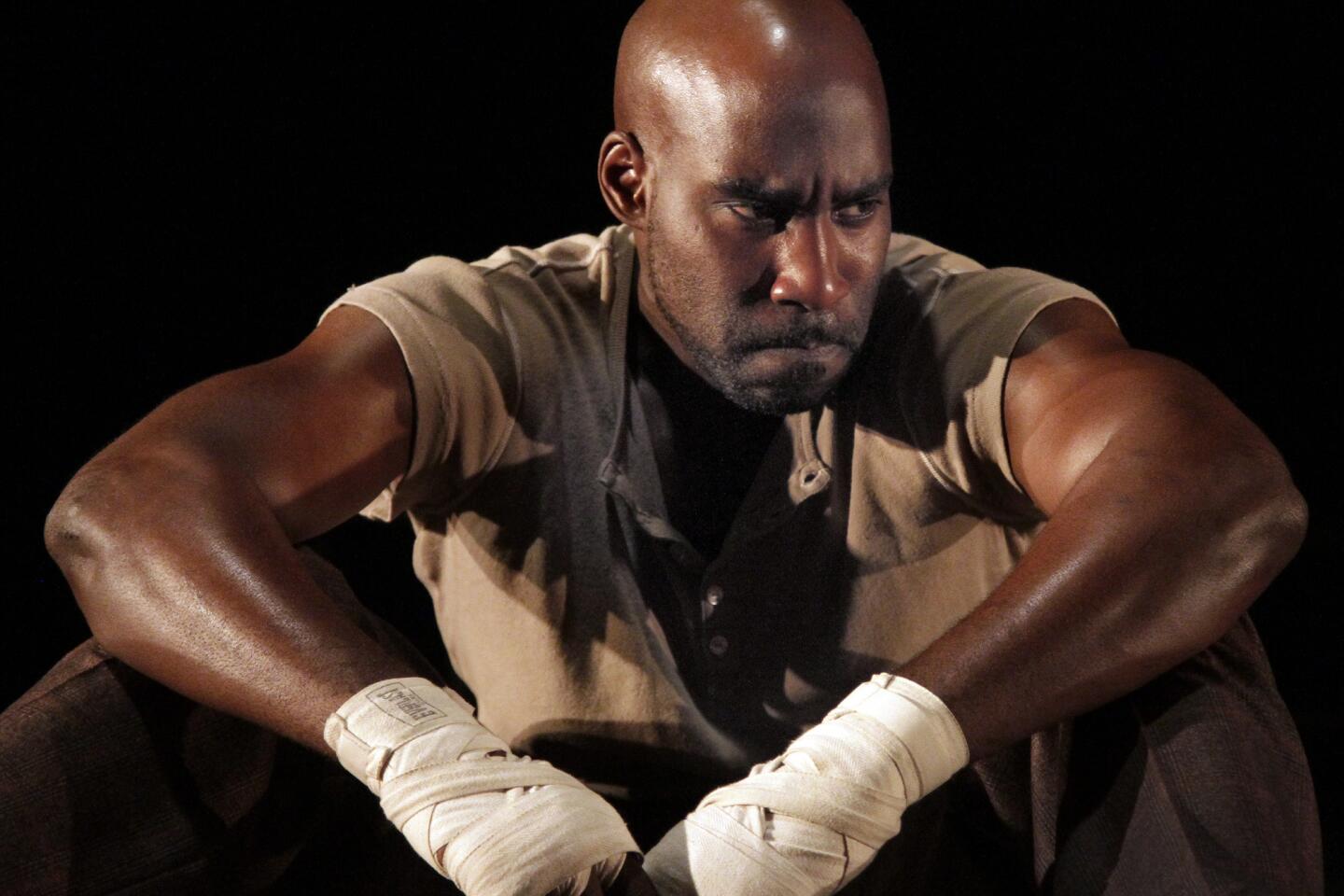

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

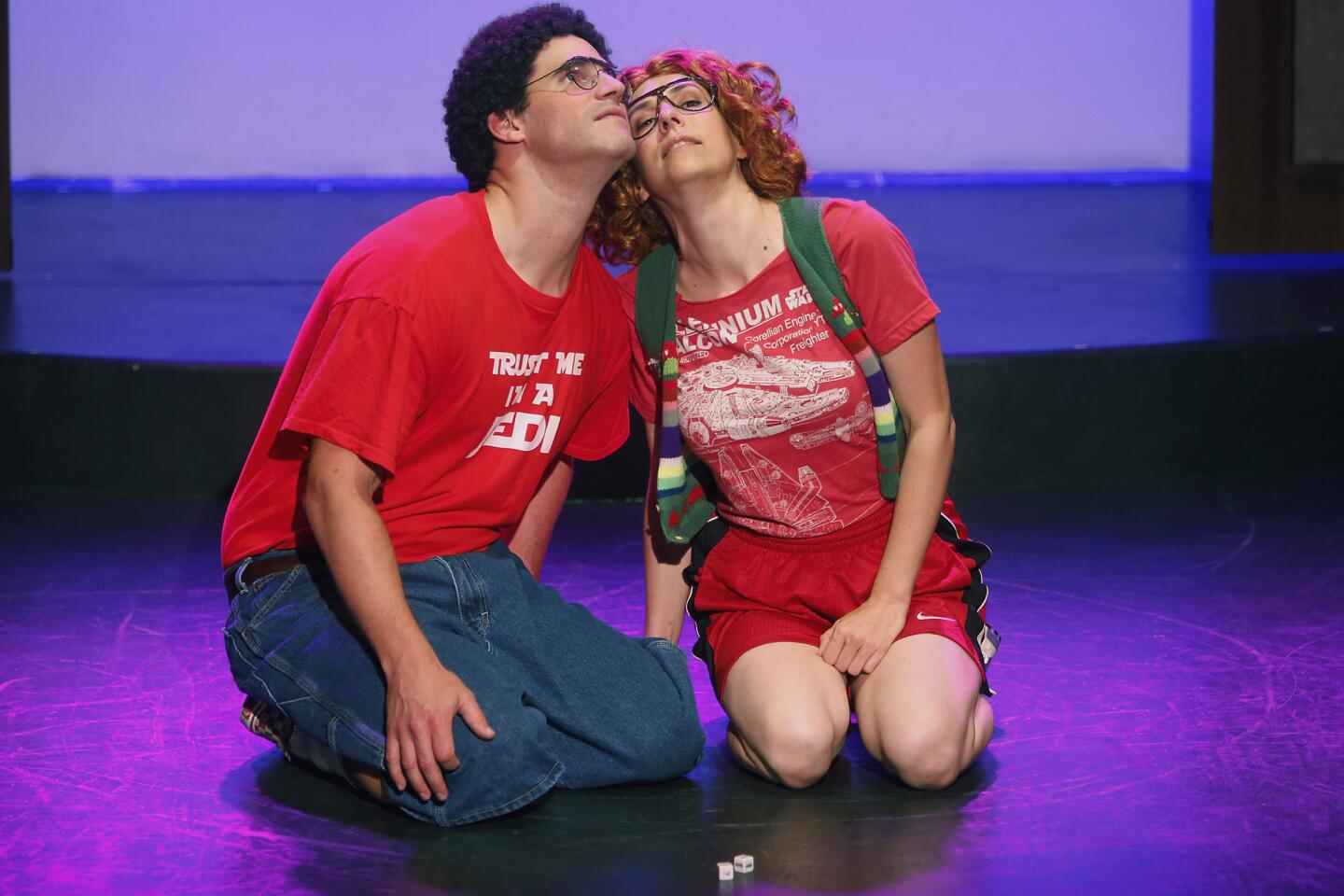

Sachs wound up writing “Heart Song,” a uniquely theatrical hybrid that premieres May 25 at the Fountain and pays tribute to flamenco through the lens of one Jewish woman’s midlife crisis. Directed by Los Angeles theater veteran Shirley Jo Finney and choreographed by the flamenco artist Maria Bermudez, it stars Pamela Dunlap as Rochelle, a fiftysomething New York City denizen who struggles over her mother’s recent death and gets dragged to a flamenco class for nonprofessional dancers by her Japanese American masseuse Tina (Tamlyn Tomita).

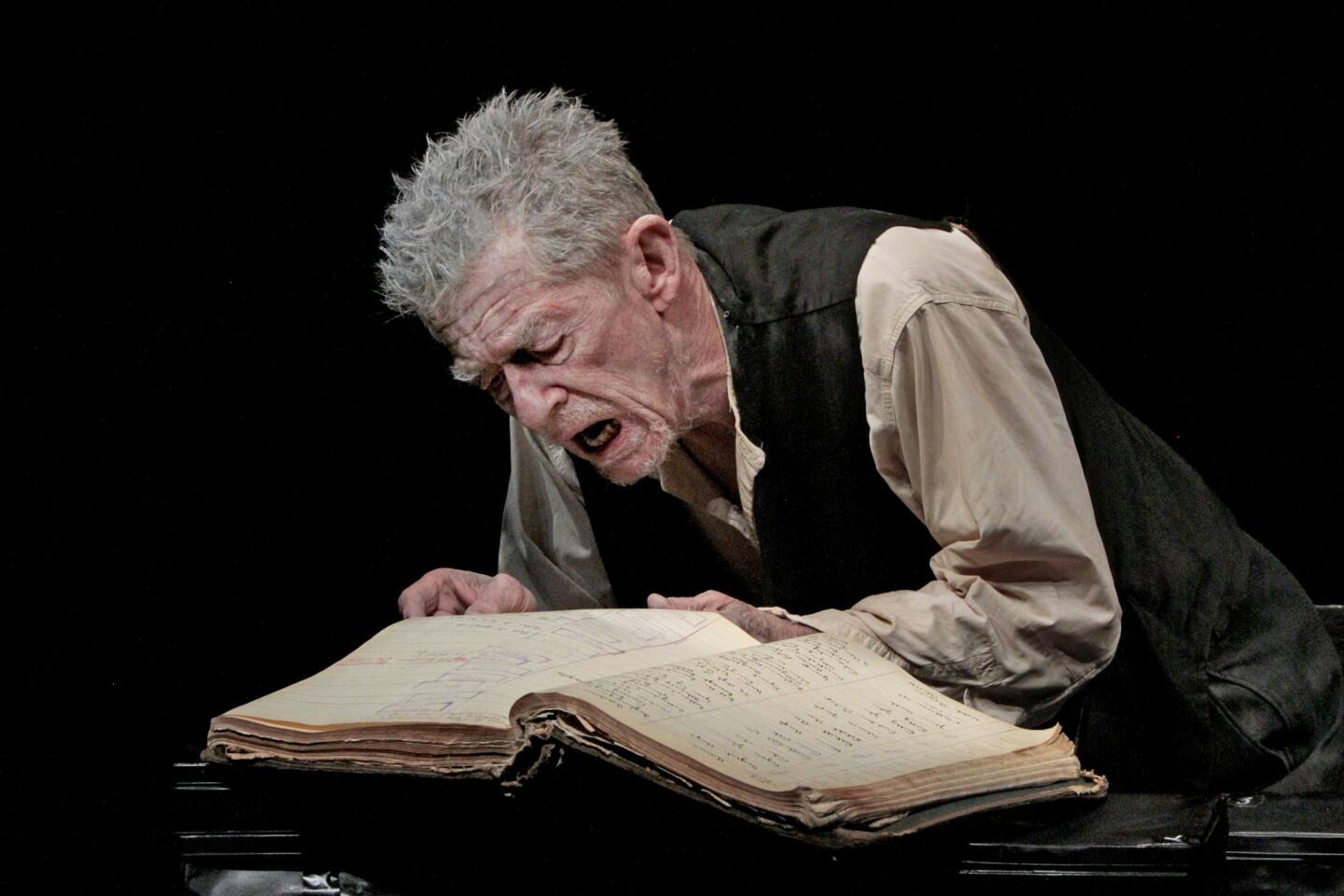

Convinced that “Jews don’t do flamenco,” Rochelle receives encouragement from fellow class-taker Daloris (Juanita Jennings), an African American cancer survivor, and reluctantly encounters Katarina de la Fuente, the fierce, Gypsy flamenco teacher played by Bermudez. (Denise Blasor will take over the role after June 15.) Katarina teaches her students how to stomp their feet, flick their wrists and fully express themselves so they can experience the heightened spiritual state known as duende. She also waxes poetic about flamenco’s origins, the shared history of persecution between Gypsies and Jews and the cante jondo, the “deep song” born from suffering and oppression.

Eventually, Katarina’s teachings infiltrate Rochelle’s psyche so that she can grieve and confront the truth of her mother’s legacy.

“What interested me in this whole subject was how art, like religion or any spiritual faith, has the power to transform and heal,” says Sachs, who recently lost his mother and still “wrestles with that loss. I wanted to explore how flamenco can give voice to what is beyond the spoken word, to that deep inner well of sorrow and pain and also joy.”

Sachs’ treatment of flamenco, filled with historical and literary references, also feels distinctly educational. This should come as no surprise when considering that the Fountain’s co-artistic director Deborah Lawlor has produced the city’s preeminent flamenco series for some 20 years. “Heart Song,” however, takes the Fountain’s outreach efforts one step further with its potential to simultaneously attract the theater’s two main audiences: traditional playgoers and flamenco fans.

“I don’t think any production has yet explained flamenco as well as ‘Heart Song’ does,” says Lawlor, who served as the play’s dramaturgical consultant and will be honored on June 15 in a “Forever Flamenco!” gala performance at the Ford Theatres in Hollywood. “The play really shows the range of flamenco and its tragic dimensions, which you don’t find in other dance forms.”

Bermudez, who lives in southern Spain and travels all over the world to perform flamenco, agrees that the Fountain’s production “is very unique. In Spain, there have been mountings of flamenco story ballets, but no one has created a drama about flamenco in this way with actors,” she says.

FULL COVERAGE: 2013 Spring arts preview

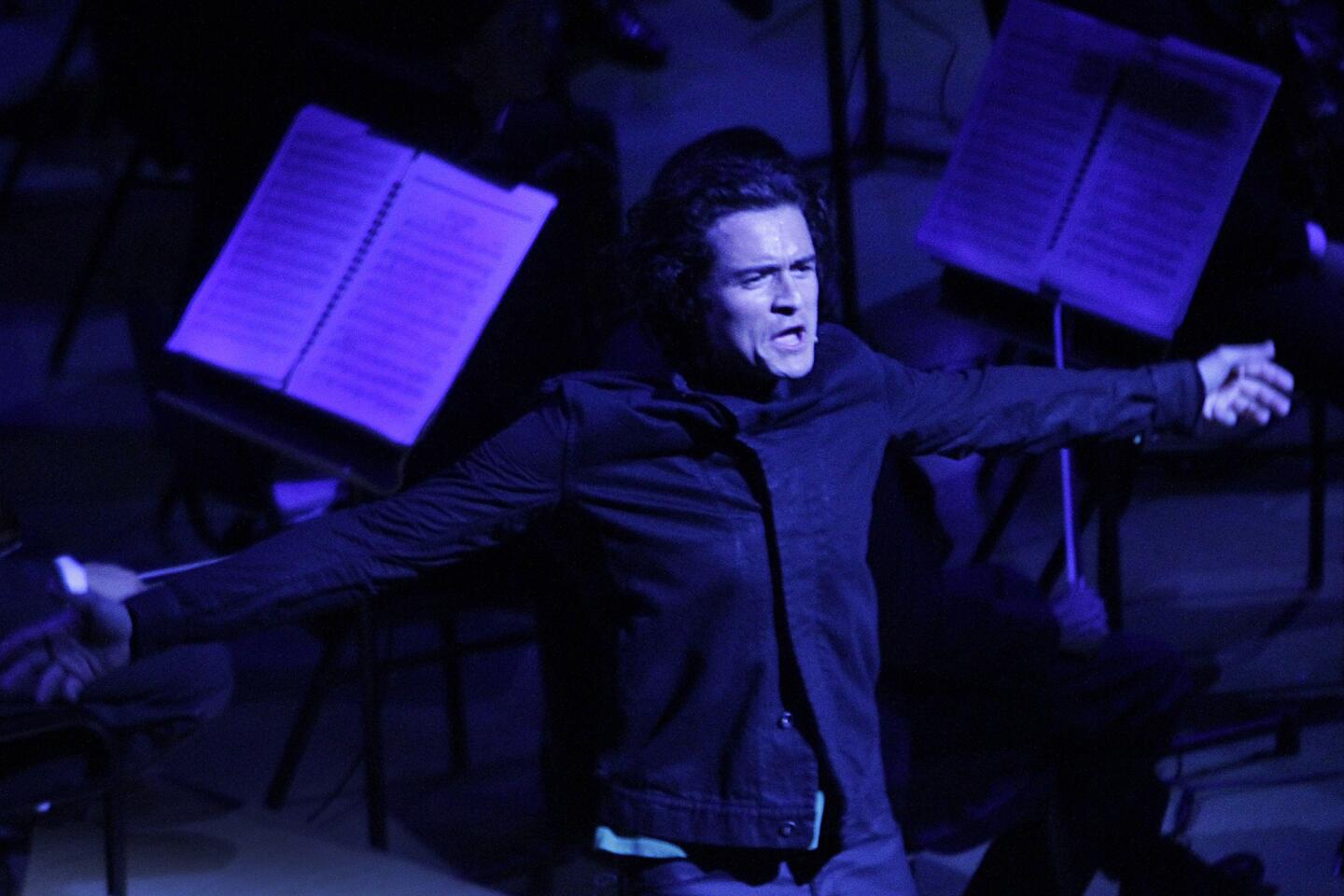

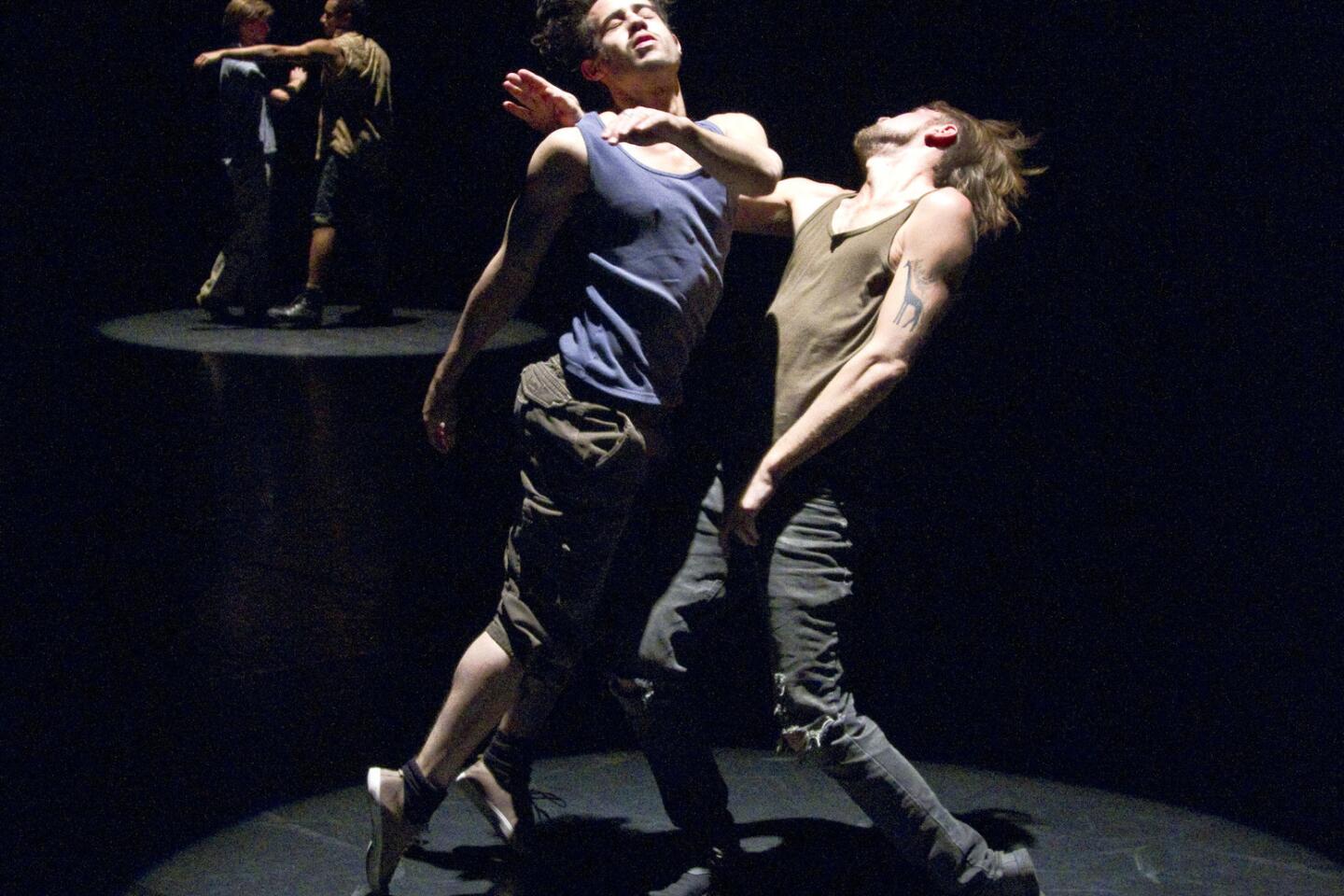

As the show’s choreographer, Bermudez faced the challenge of crafting movement that everyone in the eight-member cast could perform while accurately reflecting flamenco’s essence. For her, casting definitely proved critical.

“One of the mistakes I’ve seen with dance-theater is to have the dancers act or have the actors dance. This is totally detrimental to both genres,” says the 51-year-old flamenco artist. “So I said, ‘Let’s get actors with movement experience and I will create a choreography for them that’s accessible, so they can be these middle-aged people who are there to connect with something interior rather than with an exterior aesthetic.”

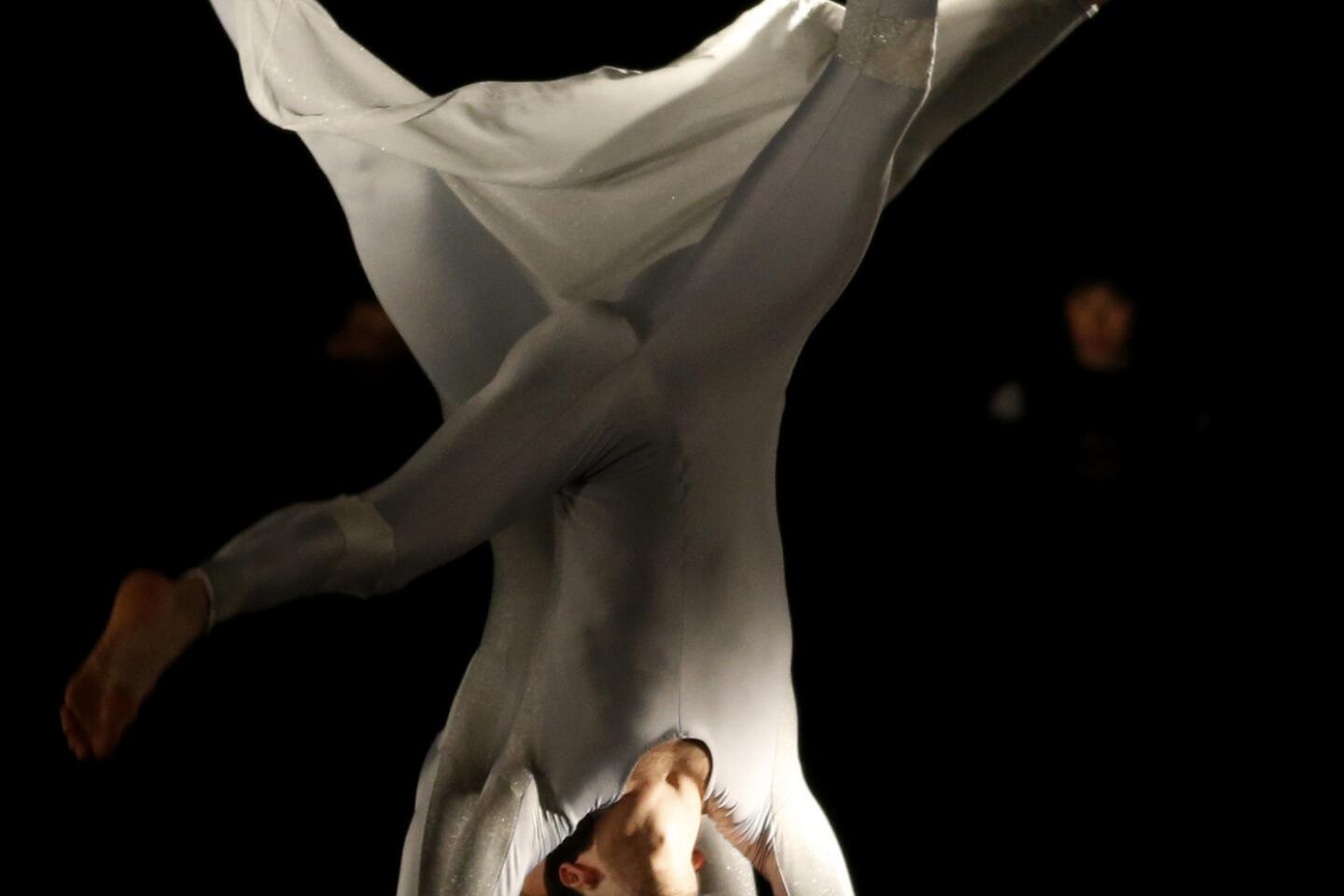

At a recent rehearsal, Bermudez’s choreography seemed to function almost as another character in the play, especially during the scene in which Rochelle first visits the flamenco class. As Katarina, Bermudez conducts a class warm-up, instructing her students to lift their arms, “touch the stars” and twirl their wrists, a motion that becomes an effective unison phrase.

Both as choreographer and performer, Bermudez has the task of conveying the flamenco class as a sacred space where women of all backgrounds can unleash their demons as a means of liberating their spirits. “For me, flamenco is about this universal cry, whether you are Jewish or African American, it is the same,” she says in a phone conversation after the rehearsal. “Pain has no color or creed.”

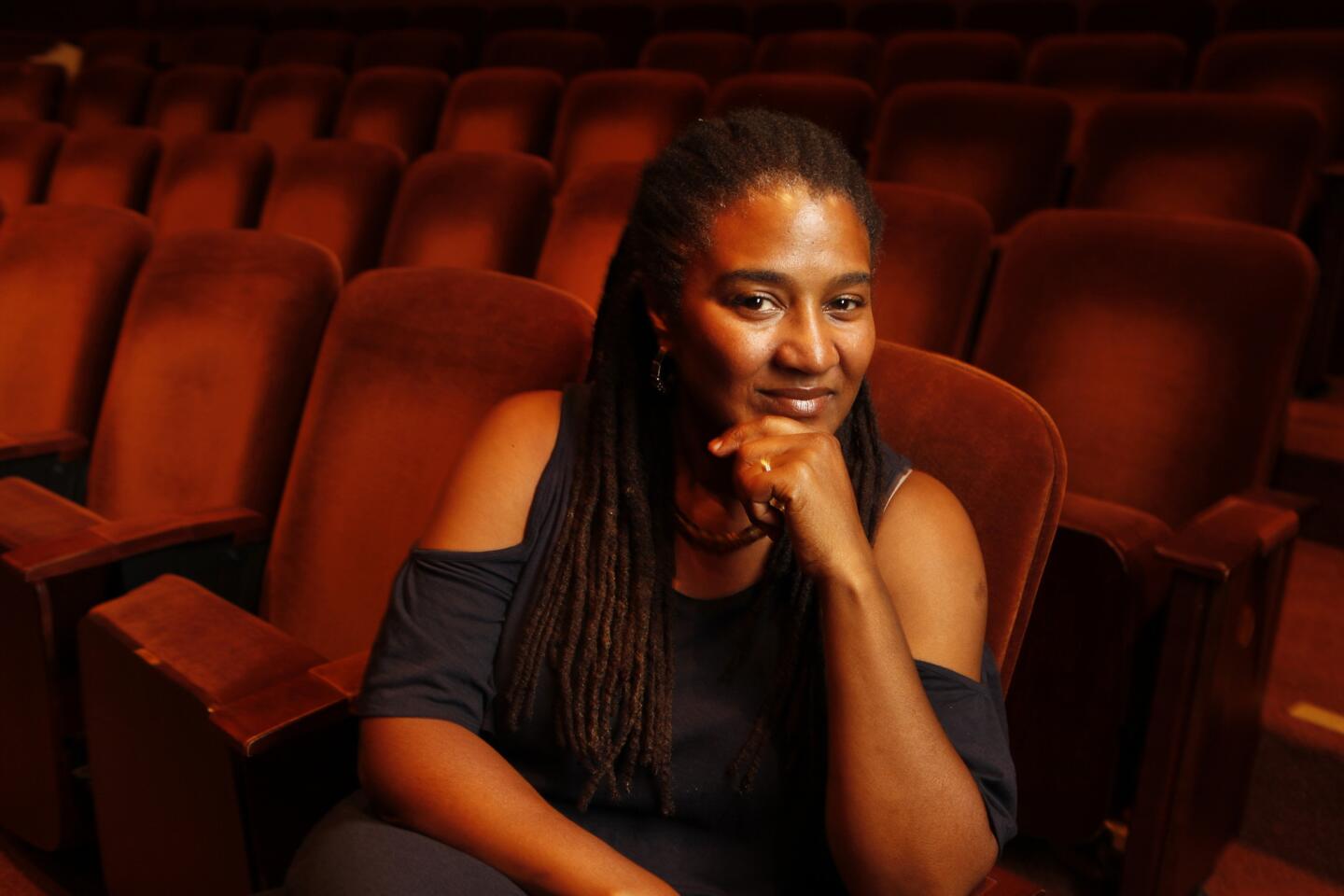

The notion of flamenco’s universal accessibility has always resonated with Finney, who collaborated with Bermudez a decade ago on developing a still unproduced, flamenco-based play called “Cry,” which sought parallels between flamenco and the blues. “What I love about ‘Heart Song’ is that it shows how interconnected we all are. Often women’s plays are very ethnic-specific, but in this piece, you see these different tribes and how they become a collective,” she says.

For Finney and her cast, the process of practicing flamenco combined with excavating the life and death themes in Sachs’ script has made for an intensely emotional experience. “In the cast we have cancer survivors, we have people who just lost their mothers,” observes Finney. “We rehearse some of these scenes and I have to say, ‘OK ladies, we got our cry. Now we have to stop and work on the script.’ Mothers and daughters, survivors and life, these have been our discussions.”

Dunlap, for example, can fully relate to Rochelle’s reckoning with her mother’s death. “The relationship with her mother was barren and the relationship I had with my mother was difficult,” says the actress, who can also be seen on “Mad Men” as Betty Draper’s formidable mother-in-law. “It is not infrequent for a play to strike a personal chord with its actors, but in this play … we are blown away by material which touches our personal lives.”

Ultimately, Sachs hopes his play and its many layers of meaning will find a “crossover audience. It would be wonderful if all our audiences came together for a shared experience,” he says. “Hopefully, it will open people’s eyes to what flamenco really is and maybe they will want to take a class themselves.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.