L.A. in the 1970s: A visual and architectural treasure trove at LAXART

- Share via

Here’s a partial list of the people and objects you can catch a glimpse of in “Environmental Communications: Contact High,” the terrific new show at LAXART gallery on Santa Monica Boulevard: the British historian and architecture critic Reyner Banham, after he grew his beard long but before it turned gray; one of the hard-candy orange spheres marking a Union 76 gas station; the intricate cast-iron interior of the Bradbury Building downtown; the fittingly over-the-top roadside sign for the Madonna Inn along the 101 in San Luis Obispo; Marshall McLuhan eating a bowl of cereal; and a barbell with a television on the end of it, being lifted by a shirtless man with the words “TV is heavy” written across his chest.

Those images are a mere sliver of the work produced by Environmental Communications, a media collective founded in the late 1960s by a group of architects, photographers and others. Working mostly from a studio on Windward Avenue in Venice, it focused on — and in certain ways became synonymous with — the Los Angeles of freeway construction, the counterculture, innovative commercial and residential architecture and in general the sort of postwar Southern California urbanism that was as freewheeling and thrillingly ad hoc as it was ragged around the edges.

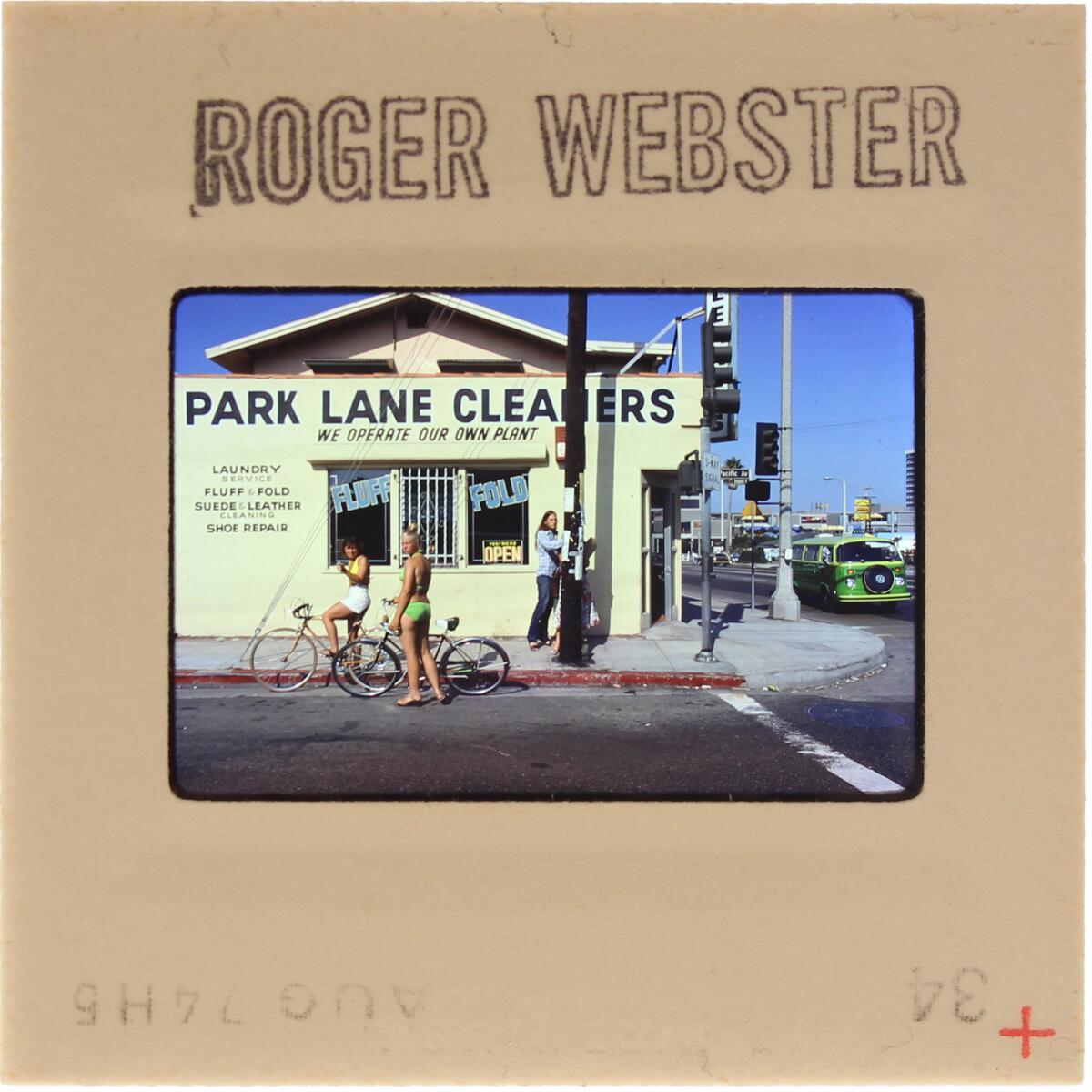

The group’s medium of choice, though it also produced zine-like pamphlets on contemporary architecture, was the 35 millimeter slide. Among its chief goals, as the wall text at LAXART puts it, was to produce a “visual taxonomy of Southern California’s urban and social geography.”

(In 1971 Environmental Communications described itself this way: “We are a matrix for the use and distribution of media to express relationships in man’s environment. We explore and document physical and cultural surroundings through the use of still photography, film, sound and video tape.”)

Environmental Communications organized its slides by theme — the categories they settled on included “Freeways/Tunnels,” “People Protest” and “Pollution” — and sold them to museums and architecture schools.

It was in this last effort that the collective was most interested in challenging the dominant cultural conversation about architecture and cities. In an era when Los Angeles, despite Banham’s best efforts, was either not taken seriously or seen as a cautionary tale for urban planners, and when images (televised and still) were quickly gaining influence across American culture, Environmental Communications realized that exploring the intersection of those categories — making images of Los Angeles their chief product — might give their work an unusual potency.

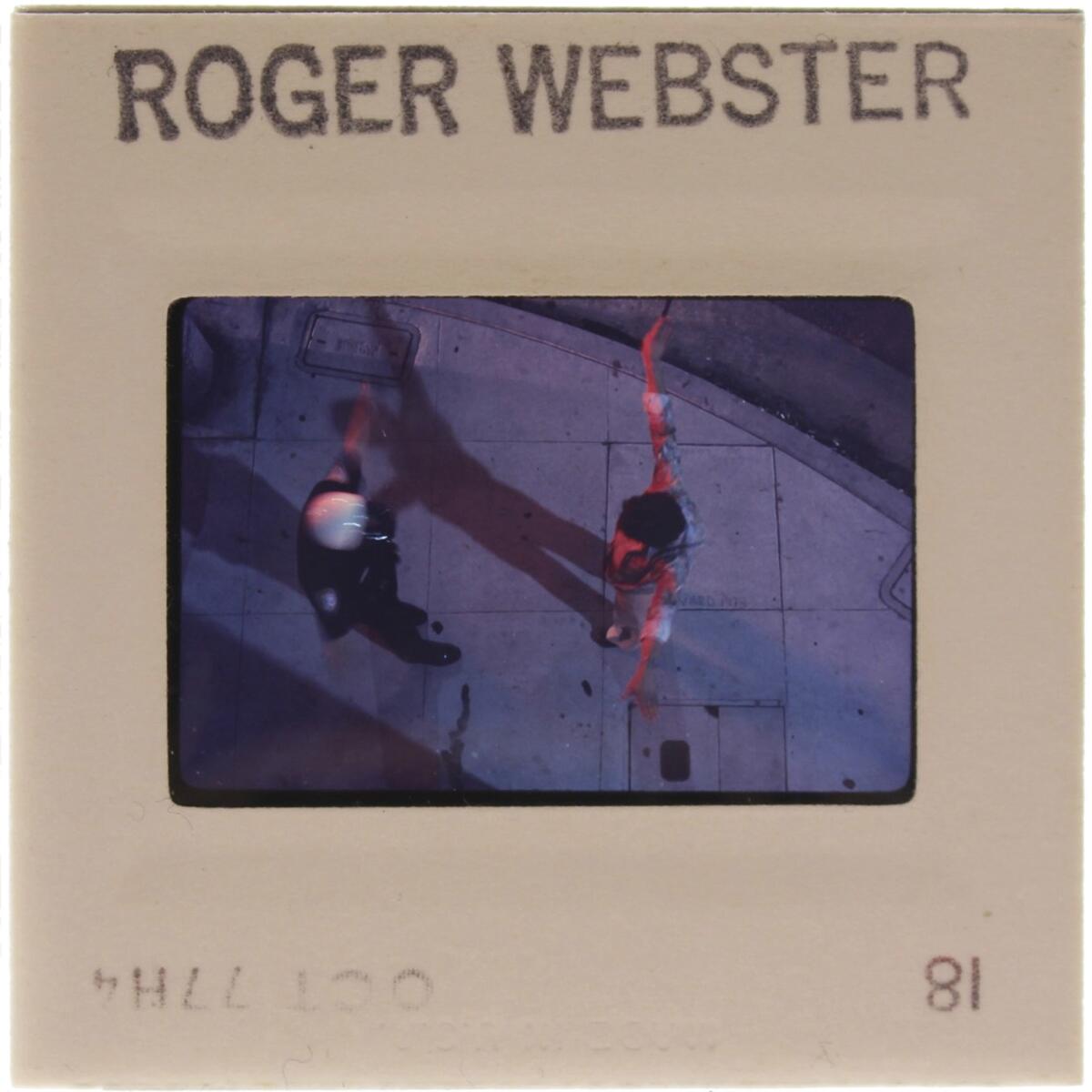

The zeal they brought to the job is clear to see in the LAXART show. Though it includes some of those pamphlets under glass as well as Polaroids, correspondence and other ephemera, the center of the gallery is given over to long rows of back-lighted 35 mm slides.

Those images — many taken by Roger Webster, one of the leaders of the collective alongside David Greenberg, Bernard Perloff and Ted Tokio Tanaka — are almost perfectly redolent of the L.A. of four decades ago, stuffed as they are with car washes, inflatable buildings, (a seemingly endless supply of) palm trees, domes, communes and the signage of the L.A. commercial strip. The images for the most part are pointedly anti-monumental, focusing not on prominent buildings by famous architects but an energetic roadside vernacular.

This was at least on the surface the city Banham extolled in his 1971 book “Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies,” which the New York Times reviewed with the following headline: “In Praise (!) of Los Angeles.” E.C. members were also heirs to an approach to studying and photographing L.A.’s populist public face that goes back to the writers Louis Adamic and Morrow Mayo in the 1920s and ’30s.

But by the time many of the group’s later images were produced, closer to the end of the 1970s, the Los Angeles dream that meant so much to Banham was beginning to curdle; images in the show of the LAPD, smoggy skies and cheaply built dingbat apartment buildings suggest the start of a dissolution and fragmentation that would reach its violent peak in the 1992 riots and its architectural one, around the same time, in the tough, often confrontational work of figures like Eric Owen Moss, Frank Gehry, Thom Mayne and Michael Rotondi.

The collective operated precisely in the years when the crisp, upbeat mid-century modernism of Craig Ellwood, Charles and Ray Eames and Raphael Soriano, among many others, morphed into the darker, more anxious and unpretty work of those L.A. School figures.

The exhibition at LAXART was organized by the architecture school at Columbia University and also appeared in Chicago. Curated and designed by Mark Wasiuta, Marcos Sánchez and Adam Bandler, it has been expanded (appropriately) for its L.A. run with help from the USC School of Architecture.

In its combination of precision and exuberance the show matches the spirit of Environmental Communications itself, whose work always a cultural contradiction in terms, a card catalog of scruffy, genial radicalism. It was a group that pursued a politics of upheaval not through aggressive rhetoric and imagery (like the Black Panthers) or violence (like the Weather Underground) but through slide shows and, later, short films shot from blimps and helicopters.

It would have helped the exhibition to have had at least one lead female curator. (For its L.A. appearance Florencia Alvarez Pacheco is credited as curatorial assistant.) There were plenty of women in Environmental Communications over the years, though their contributions were hardly front and center. Some of the slides celebrate a particularly male point of view.

More attention to the question of what it was like for a woman to produce imagery alongside the men in the group (or for women to appear as subjects in their photographs) would have added a useful perspective, if not something closer to an outright corrective.

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.