How did yarn paintings find their place in Mexican folk art? Fowler Museum tells the tale

- Share via

Anthropologist Peter T. Furst was working on his PhD in western Mexico in the mid-1960s when he discovered the vibrant yarn paintings of the Wixáritari people, commonly referred to as the Huichol.

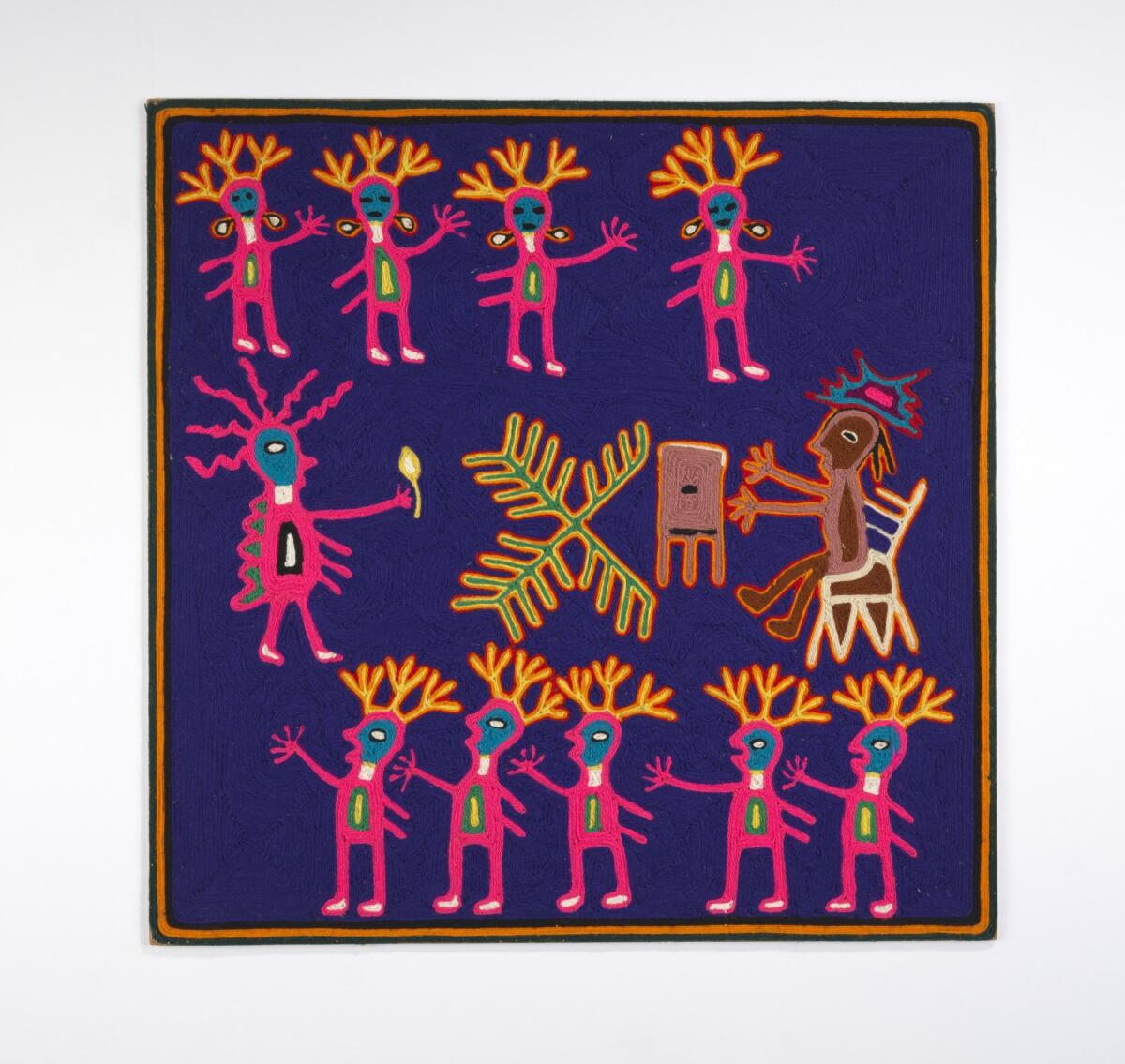

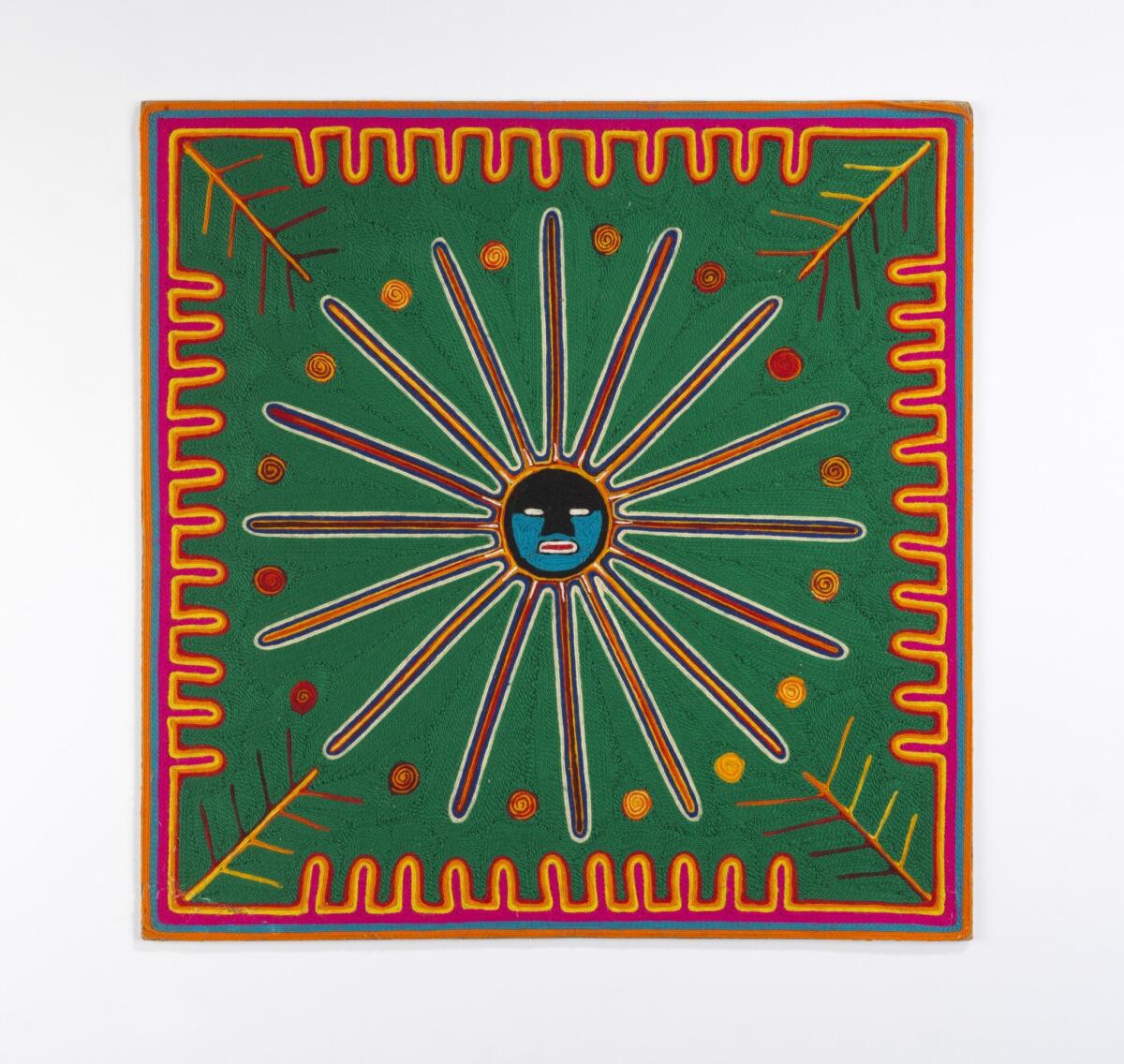

He was captivated by their nierakate, strands of yarn laid into illustrations carved on a wooden board coated with beeswax. Brightly colored, detailed works depicted sacred animals, holy plants and ancestral figures.

“There’s a long-standing tradition of using colored yarn and fabric as a way to represent and interact with divine supernatural figures,” said Patrick A. Polk, curator of Latin American and Caribbean popular arts at the Fowler Museum at UCLA.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

After spotting one of the paintings in a government building, Furst sought out the early works of Wixárika artist and self-described shaman Ramon Medina Silva and his wife, Guadalupe de la Cruz Ríos. Furst began acquiring their traditional yarn paintings, many of which are on view in “The Spun Universe” at the Fowler. A few ritual objects such as a drum, miniature shaman chair, hat and basket are displayed next to the corresponding artwork.

Silva, who had deep knowledge of the mythological traditions, was prompted by Furst to illustrate the sacred stories. This often entailed the ritual use of peyote and the resulting shamanic visions.

“The moment of innovation was Furst’s suggestion to Silva to move from figurative artwork — basic imagery of scorpions and birds — to more mythological narratives and themes of ritual activity,” Polk said. “Silva’s art changed in how he presented the traditions and cultural knowledge of the indigenous folk art.”

With interest in folk art taking off in Mexico and the counterculture of the psychedelic ’60s in full swing, private collectors and institutions in the U.S. began taking notice, seeking out art in cultures with different world views. Medina Silva was soon propelled into global notoriety.

“It was perfect timing,” Polk said.

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

Female artists gather at Hauser Wirth & Schimmel for a joyous flash mob

Getty Museum aims to acquire 16th century Parmigianino painting

Doug Aitken's 'Electric Earth' will shake the MOCA landscape

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.