What to see in L.A. galleries: Andrew Masullo’s off-kilter world, plus Gary Lang and Ruth Pastine

- Share via

Andrew Masullo’s modestly scaled paintings at Zevitas Marcus are visual analogs to impossibly specific — and oddly anonymous — experiences.

The one in the front window is titled, inventory-style, “6432,” and captures the satisfactions of singing in the shower, belting out off-key oldies as hot water drums on your skull. Painted the same red, yellow and blue, “6400” conveys what it feels like to finish a tough job and crack open a cold one, knowing you’re free until sunrise.

Also painted in nothing but blazing primaries, “6436” embodies the uplift of bumping, unexpectedly, into an old friend. And “5982” recalls the soul-expanding release of seeing the city skyline shrink in the rear-view mirror as you speed out of town.

Such precise memories and the sentiments they trigger come rushing to the forefront of “Pretty Pictures and Other Disasters,” the New York painter’s fifth solo show in Los Angeles since 1990. They’re the tip of the iceberg.

Other colors expand the palette of Masullo’s eccentrically configured compositions. Black and white figure prominently, but so do pink, orange and baby blue. Green, gray and purple occasionally appear, extending the range and amping up the intensity of the quotidian dramas these animated abstractions elicit.

Masullo’s colors are wonderful, but his paintings are great because of their shapes and the way they’re composed: off-kilter, out of sync, filled with more vim and verve than just about anything else out there. Sometimes Masullo lodges solid chunks of color into slippery jigsaw puzzle-style setups. At others, he blots out missteps. In both cases, he wiggles silliness and seriousness into a dynamic mix.

As a painter, Masullo is the most playful shape-maker of his generation. All of his asymmetrical rectangles, imperfect circles and idiosyncratic blobs, dollops and puffs conspire — and collaborate — to excite the imagination.

You can’t help but share your responses to his gregarious works with others. That’s the paradox — and brilliance — of Masullo’s abstract pictures: Each makes you feel as if it were made for you and you alone, while letting you know that the peculiarity of your response is nothing special.

Others matter. And that makes all of us just a little bit more civilized.

Zevitas Marcus, 2754 S. La Cienega Blvd., Suite B, Los Angeles. Closes Saturday. (424) 298-8088, www.zevitasmarcus.com

Gary Lang knows a thing or two about space. His magnificent exhibition of abstract paintings at Ace Gallery in Beverly Hills fills the towering main space with the perfect combination of visual wallop, funky nuance and breathtaking sensitivity.

The sheer size of his 10 canvases and panels in the cathedral-like main space — some round, others rectangular and many that measure between 10 and 20 feet on a side — suggests that they might be monumental instances of male egomania: the visual equivalent of mansplaining.

But Lang is no egomaniac. Nor is he out of touch with the mysteries of conversation — the myriad ways dialogue drives us to intimate discoveries by taking us outside of ourselves, where we see the multifaceted complexity of experience, not to mention existence.

That’s because Lang also knows a thing or two about time. His paintings are all about rhythm.

They live and die by their capacity to get viewers moving, to activate our eyes and minds by drawing us into all sorts of back-and-forths, give-and-takes, to-and-fros.

Pragmatic and grounded, his paintings work their magic up close. As you stumble and stutter your way through his multi-layered compositions, momentum shifts and you’re off and running, your imagination flying through abstract spaces with no limits.

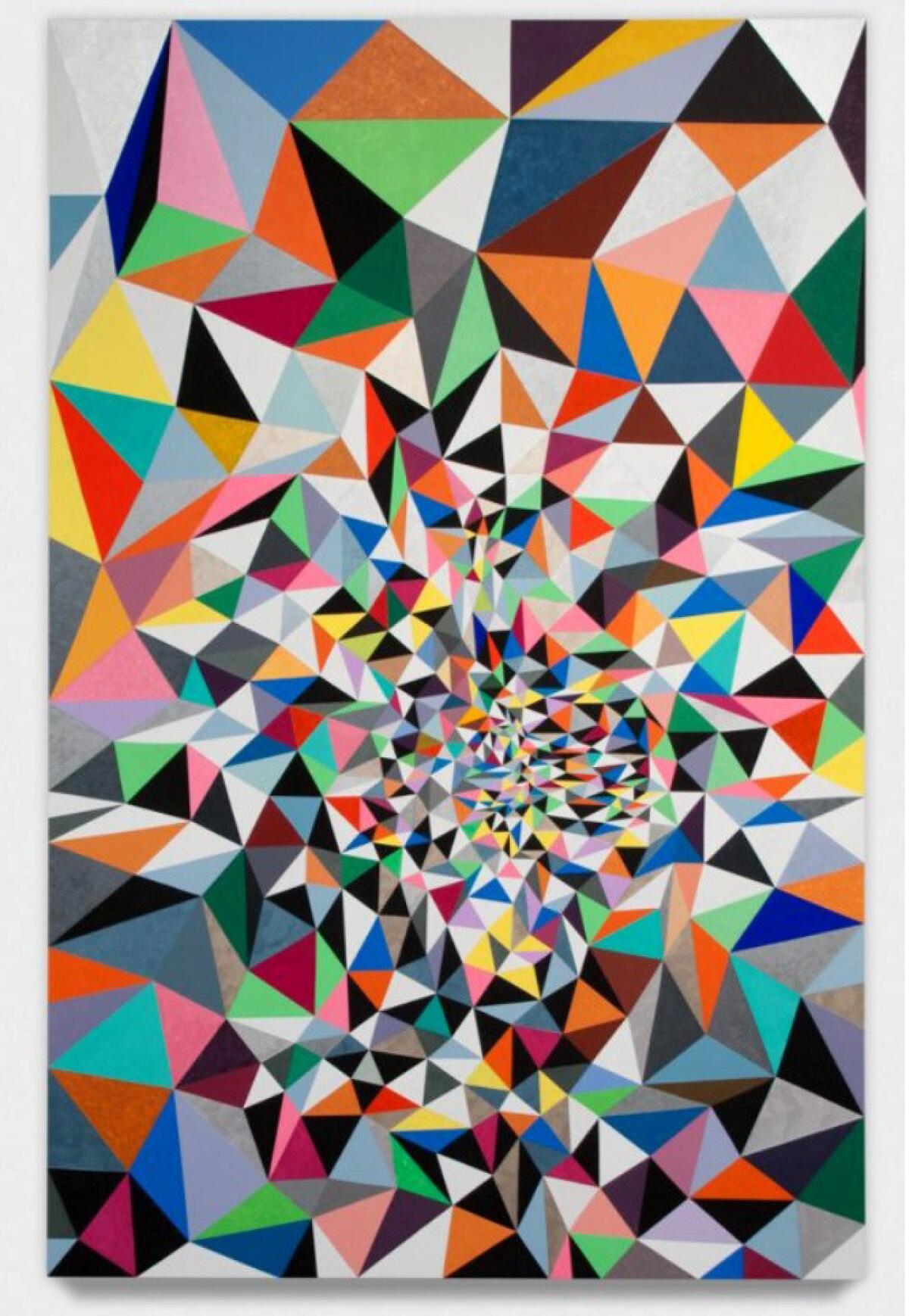

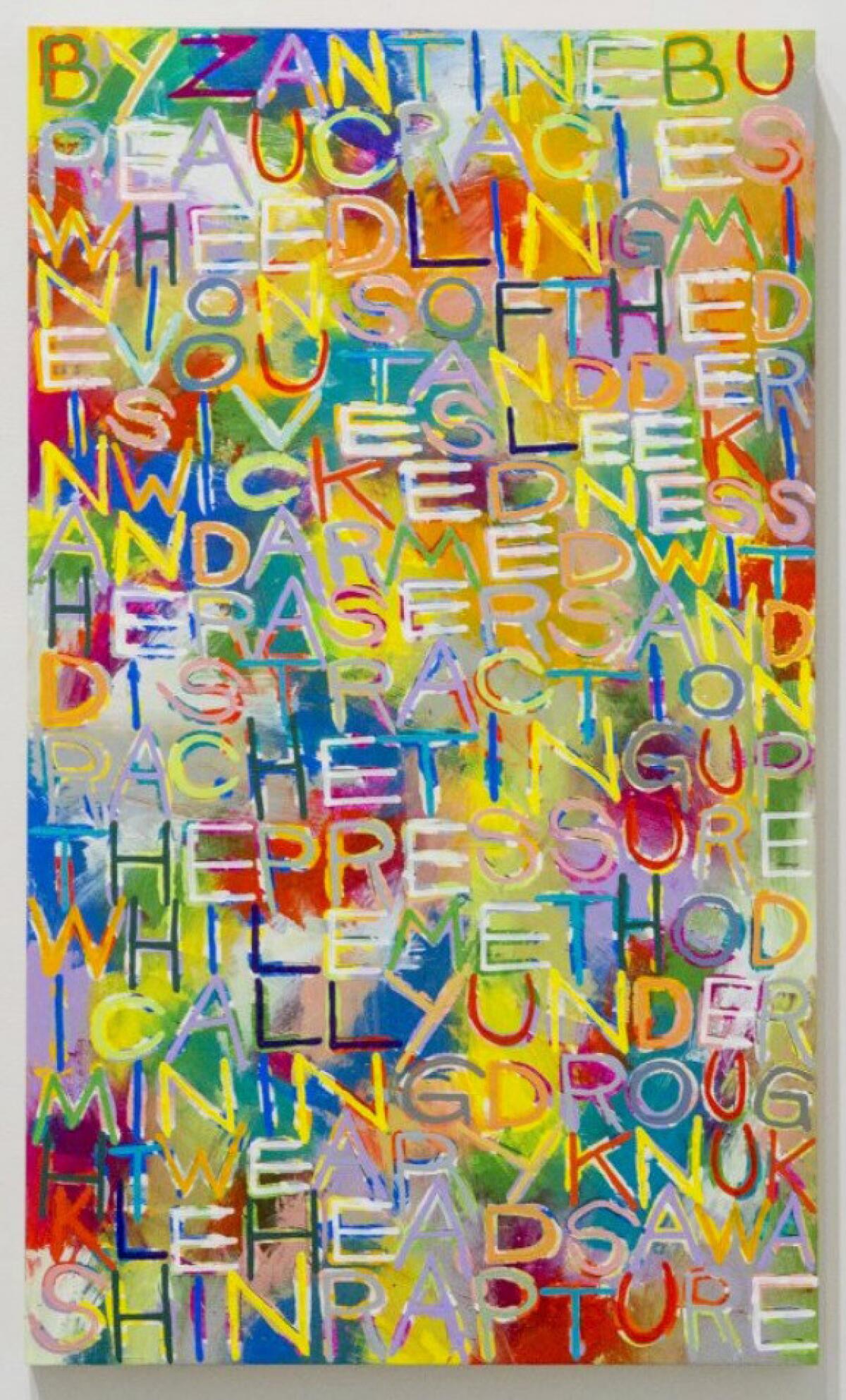

To fall into a painting by Lang is to fall into a world with no road maps or landmarks. You feel your way through the unnaturally beautiful colors, the vibrating triangles, the concentric rings of pulsating energy and the brushstrokes that seem to be illuminated from within. The exploratory tentativeness of the activity starts out cautious, often suspicious, even defensive.

That happens in small galleries that, like antechambers, flank the main space’s entrance. Lang has installed five paintings of poems and two abstract labyrinths. Both series take you back to the basics, sounding out words and getting lost in the details. There’s a sexual charge to such eye-opening, spine-tingling instants of acute attentiveness.

Titled “Rising,” Lang’s exhibition is a secular version of the Christian ascension: a celebration of optimism and uplift, of those moments when our best selves leave our worst selves in the dust and our souls open to horizons beyond any previously imagined.

It’s also a terrific complement to a small upstairs exhibition upstairs, where paintings and drawings by his wife, Ruth Pastine, are displayed. The dialogue between the two shows adds another layer for viewers to savor.

Ace Gallery, 9430 Wilshire Blvd., Beverly Hills. Through Nov. 12; closed Sundays and Mondays. (310) 858-9090, www.acegallery.net

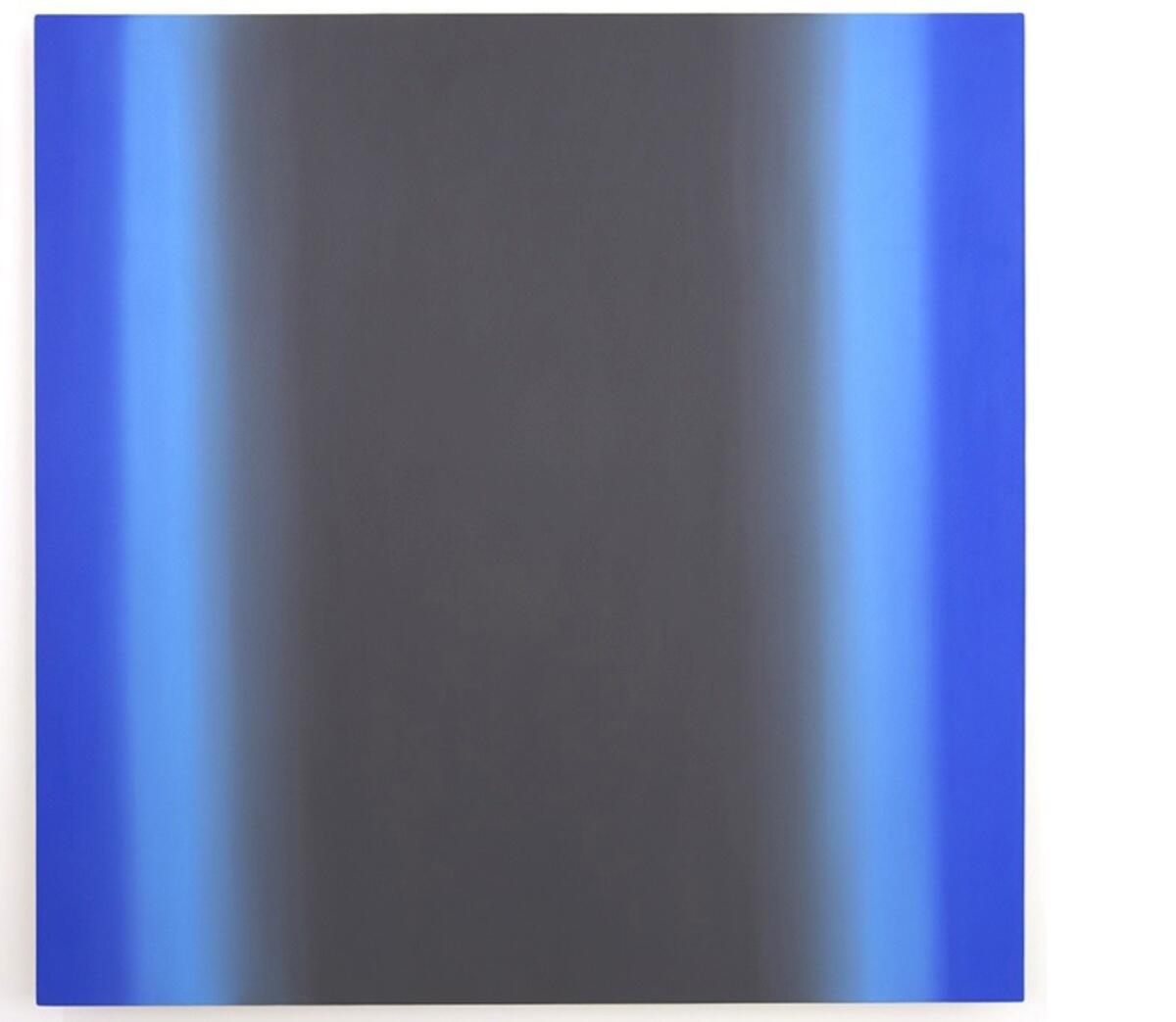

Each of Ruth Pastine’s six paintings and two drawings in a second-floor space at Ace Gallery invites visitors to settle on a single moment — a tiny slice of time that doesn’t seem to amount to much because it’s so fleeting.

But in Pastine’s hands, that incidental split-second expands — with uncanny frequency. The intensity also picks up. The supersaturated colors, in simple, minimalist compositions, make you breathe deeply — first to catch your breath and then to get enough oxygen so as not to miss anything.

That happens so often in “Ethereal Materials” that time seems to slow down. An intoxicating combination of sensuality and serenity suffuses the space. Whispering, rather than screaming, Pastine’s paintings suggest that art is not timeless because its impact is unchanging, but because it is always changing. Mystery fills each moment with infinite possibility.

Pastine’s six midsize oils on canvas have been installed on three walls. On the north hang a pair of red vertical paintings. On the south hangs a dark blue horizontal canvas. And in between, on the long east wall, Pastine moves viewers from red to blue, or blue to red, depending on where you begin.

The trip takes you through a range of purples, pinks and burgundies, then grays and sky blues before introducing shades so dark they rival the night sky’s velvety richness.

There’s no end to the quiet beauty of Pastine’s paintings, which play well with one another because each gives you so much time and space of your own. It’s a dramatic and satisfying complement to the paintings downstairs by her husband, Gary Lang.

Opposites may attract. But more nuanced differences generate deeper conversations.

Ace Gallery, 9430 Wilshire Blvd., Beverly Hills. Through Nov. 12; closed Sundays and Mondays. (310) 858-9090, www.acegallery.net

The immersive installation at Young Projects in West Hollywood is notable for two reasons. The first is conventional. The second is troubling.

The upside first: “Daisy Redux: Rain Machine (Daisy Waterfall) 1969 by Andy Warhol With Digital Augmentation by Refik Anadol” is a historically significant exhibition because it gives visitors the opportunity to experience a rarely seen work by Warhol — sort of.

About half of Warhol’s “Rain Machine (Daisy Waterfall)” is presented. On a wall of a darkened gallery hang 65 images of a daisy, arranged in a wall-size grid. Printed with a lenticular process, each supersize flower appears to be three-dimensional, in the manner of a novelty postcard.

When Warhol exhibited “Rain Machine (Daisy Waterfall)” in 1971, in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Art + Technology exhibition, it included 70 images as well as a sprinkler system suspended over a large trough on the floor in front of the wall of flowers. Electric motors pumped water from the trough to the ceiling, creating an indoor rainstorm.

Today, Warhol’s artificial rain has been replaced by media artist Anadol’s computer-generated raindrops. Projected onto an otherwise invisible scrim, the raindrops appear to fall from the ceiling and splash into the open top of a sleek black box. A recording of rainfall adds to the illusion. The audio includes the melodic plunking of a piano’s keys.

Four versions of “Rain Machine (Daisy Waterfall)” once existed. Three were damaged by the splashing water and eventually destroyed. All that remains of the fourth are the lenticular prints on display here, which belong to Maurice Tuchman, senior curator emeritus of LACMA and the organizer of Art + Technology. He organized the exhibition with gallerist Paul Young and Adlin De Domingo, a Beverly Hills inventor.

Its unwieldy title only begins to suggest the thorny issues it raises.

Before a visitor gets a glimpse of the digitally enhanced version of Warhol’s work, you pass through a darkened maze. Digitally projected raindrops illuminate the labyrinthine space. Some of its walls are floor-to-ceiling mirrors. Others are translucent scrims. Still others are painted black.

This part of the installation is mesmerizing, a kind of Light and Space work for the selfie generation. Like Random International’s “Rain Room” at LACMA and Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Mirrored Room” at the Broad, it has very little to do with Warhol’s “Rain Machine (Daisy Waterfall).”

As a whole, “Daisy Redux” has more in common with architecture than with art — not because it alters one’s experience of interior spaces, like Jennifer Steinkamp’s digital projections, but because it is a form of renovation.

Think modest midcentury masterpiece stripped to the studs and rebuilt as an aesthetically incompatible extravaganza. “Daisy Redux” is a similar sort of bells-and-whistles miscarriage of historical preservation.

Even worse is its suggestion that art needs renovation. Art is not a fixer-upper. It’s something to be seen exactly as it is.

Young Projects, 8687 Melrose Ave., #B230, West Hollywood. Through Feb. 10; closed Saturdays-Mondays. (323) 377-1102, www.youngprojectsgallery.com

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

Times art critic Christopher Knight’s latest reviews

Times theater critic Charles McNulty’s latest reviews

Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne’s latest columns

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.