Norton Simon: A look at the art purchase that transformed the collector

- Share via

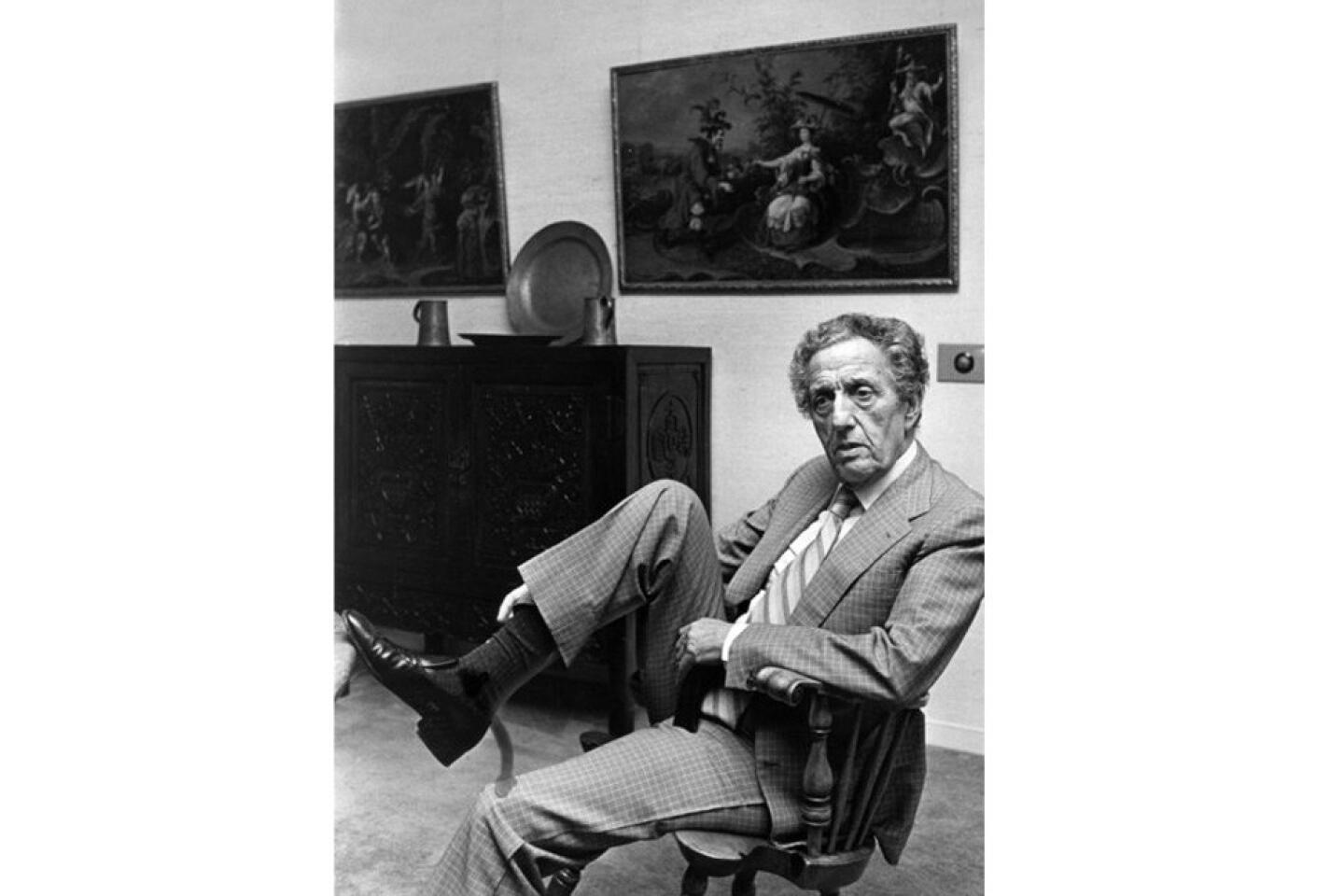

If there was a single day when Norton Simon declared himself a world-class art collector, it was April 18, 1964.

That’s when his foundation made a $4-milllion deal to buy the entire inventory of the New York gallery Duveen Brothers, along with its library and five-story building on East 79th Street. The inventory included nearly 300 European paintings, drawings and sculptures; 100 pieces of French, Italian and English furniture; and 400 decorative objects, including tapestries, carpets and stained glass.

A tycoon in the business world who started collecting art in the mid-1950s, Simon did not intend to buy every last bit of stock from the firm known for selling Old World treasures to the likes of Andrew Mellon, J.P. Morgan, Arabella Huntington and Henry Frick.

He merely wanted “a lot of stuff,” according to Edward Fowles, who acquired the gallery after the death of Joseph Duveen, a fabulously successful art dealer. But when Fowles hesitated, fearing that Simon would strip the gallery of its most valuable material, the California collector asked, “Why don’t I buy the whole thing, lock, stock and barrel, including the building?”

Fowles quickly got over his shock. Then 79, he saw an opportunity to retire with enough money to provide for himself and his employees.

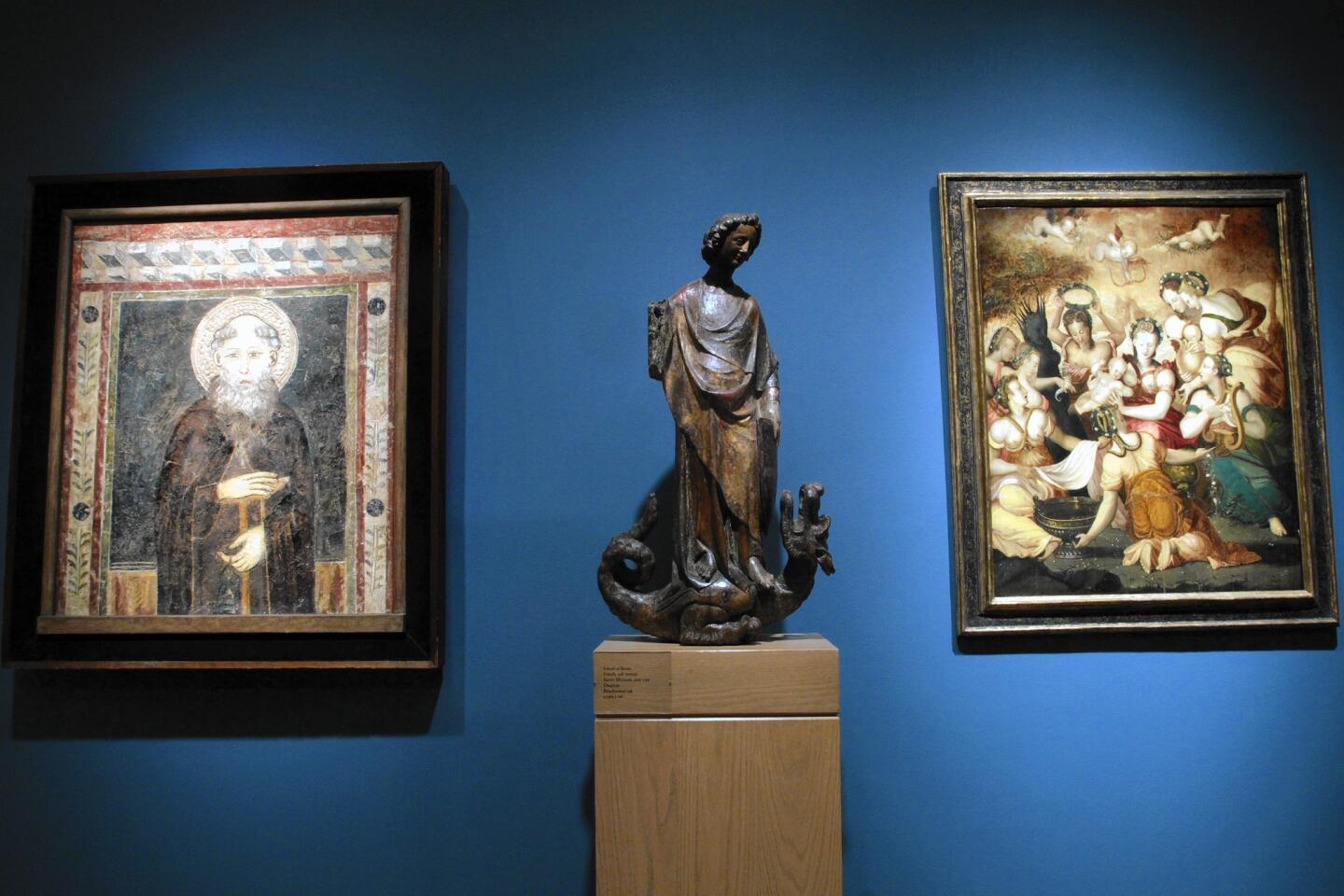

The rest is history. But the story is about to be revived, reexamined and expanded at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena. “Lock, Stock and Barrel: Norton Simon and the House of Duveen,” opening Friday, will present 99 Duveen objects, most pulled from storage to be shown for the first time.

The exhibition catalog, including an essay by retired curator Sara Campbell, will document the 1964 transaction and its aftermath. A lecture series will explore Joseph Duveen’s national influence as a tastemaker.

The multifaceted program is partly a 50th anniversary celebration of Simon’s spectacular purchase, says Carol Togneri, chief curator at the museum. But it also acknowledges that the museum is “going forward, digging deeper,” with the help of continuing research and improvements in conservation technology.

“Keep in mind that there were originally about 800 objects in the Duveen stock,” Togneri says. “About 130 of them remain at the museum. Of those pieces, there are roughly 20 on permanent display. That leaves the question: Why? What’s still here? What are we dealing with?”

Like many museums, the Simon has space to show only a small percentage of its collection at any one time. But the majority of the Duveen pieces have never been displayed because they are too big, do not measure up to the museum’s standards or do not fit in with the other works.

Fifty years after the purchase, it may seem strange that Simon opted for the entire inventory only to sell most of it later, including an intricately carved 16th century French cabinet now at the J. Paul Getty Museum. But as a businessman accustomed to transforming undervalued companies into highly profitable enterprises – he built a bankrupt orange juice bottling plant into Hunt Foods and Industries, and built a corporate empire that included Wheeling Steel Corp., Ohio Match Co. and McCall Corp.-- he surely expected to recoup his investment by selling what he didn’t want and watching the value of prime pieces grow.

Simon’s coup was introduced to the public in 1965, when he lent about 200 Duveen works to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art for its opening. A long-running effort to persuade Simon to give his collection to LACMA finally ended in 1971, when he withdrew from the board of trustees and sold more than 300 Duveen objects. He took charge of the failing Pasadena Art Museum in 1974 and reopened it as a showcase for his own collection the following year.

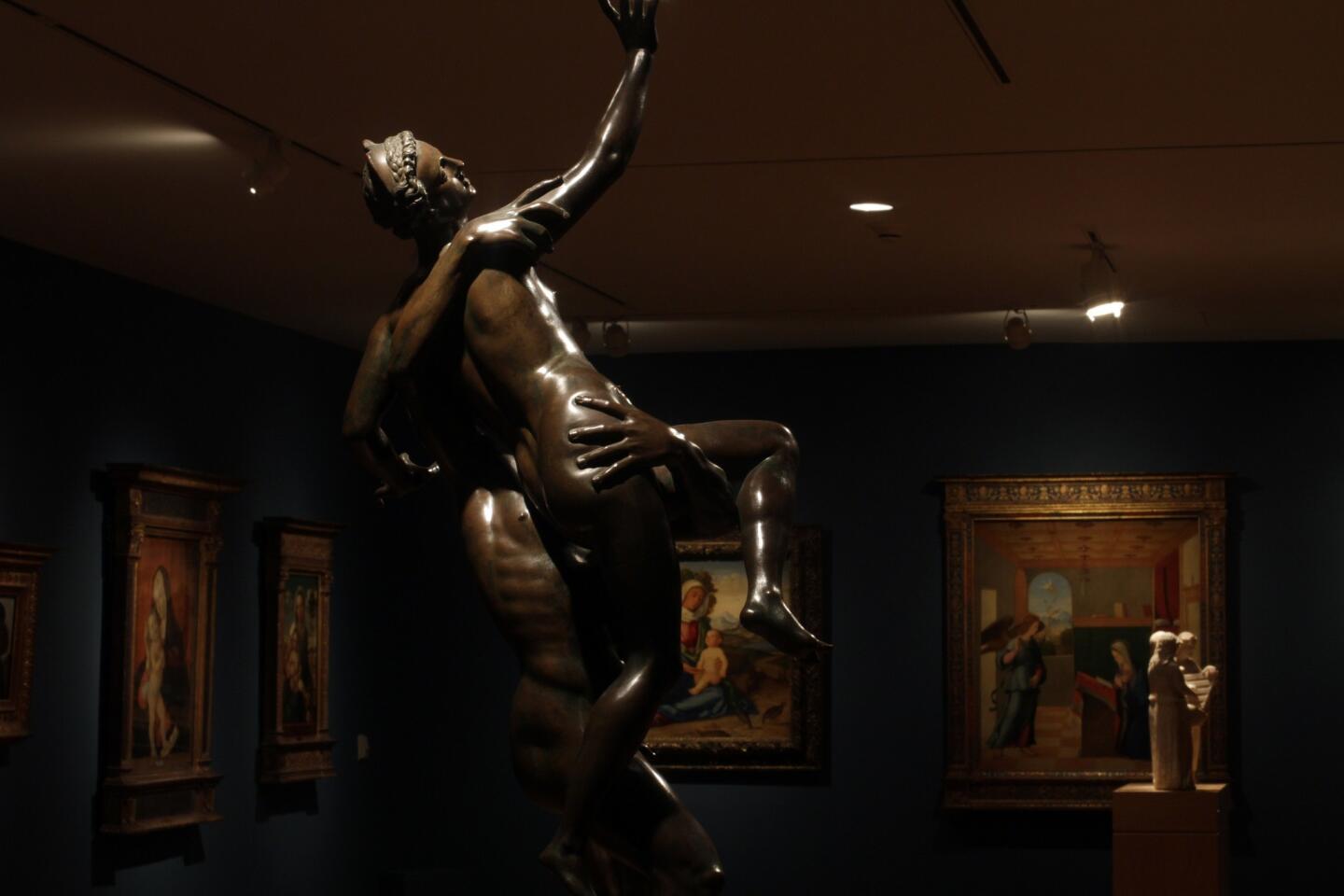

The exhibition features a few choice examples from the Duveen collection that are usually in the permanent collection galleries, including “Bust Portrait of a Courtesan,” a sensuous painting by the Italian artist known as Giorgione; “Bacchante Supported by Bacchus and a Faun,” a delicately detailed French terra cotta sculpture by Clodion; and “Happy Lovers,” a Rococo confection by French artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

But there are dozens of surprises. Who knew that the Simon museum had retained an embroidered silk cape made for a Spanish knight from the Duveen stock or three 19th century Chinese porcelain figures? Or that a Titian-style portrait with a window into an underlying painting would emerge from the museum’s storage?

The painting is merely a copy of Titian’s “Portrait of Giacomo Dolfin” in LACMA’s collection, but when an X-ray indicated that the portrait was painted over another composition, a conservator removed a small section of the background.

“One part was opened up, where there was an eye,” Togneri says, “and then more and more until it was agreed that the picture underneath was probably not as good as the painting above. But Mr. Simon said, ‘Why close it up? It might be of interest to people to see this.’ So it was opened up a bit more to show the bridge of the nose and the eyes. We will be showing the X-ray too. I don’t know if we will ever come to a decision about what is underneath, but this is all part of the process.”

Among many other paintings, visitors will discover that Simon, who had no interest in British painting and no desire to compete with the superb collection at the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, kept three 18th century British paintings from the Duveen trove: “Lady Hamilton as ‘Medea’” by George Romney and two portraits of children by Nathaniel Hone.

Another revelation is “Fête Champêtre,” or “Country Festival,” a suite of seven paintings that formerly decorated an English country house. The work is attributed to the circle of 18th century French artist Jacques de Lajoue, but some scholars think the artist may have been German, Togneri says.

Simon was a shrewd collector, known for consulting experts far and wide but ultimately making up his own mind about potential acquisitions — and then making complicated deals. In the case of the Duveen purchase, he drew up two separate agreements with Fowles before making a commitment. One contract, later consummated, gave the Norton Simon Foundation a 90-day option to purchase Duveen’s outstanding inventory and facilities for $4 million over a period of 10 years.

The other contract guaranteed that Simon’s foundation could buy 18 works over nine years for $1,525,750 and gave him an option to purchase three additional paintings for a total of $835,000. The pair of agreements gave Simon time to examine the inventory and bow out of the “lock, stock and barrel” deal without losing the most desirable pieces.

As Togneri and Campbell point out in the catalog, the Duveen adventure ultimately shaped Simon’s legacy at the museum. He initially focused on French Impressionism, but his viewpoint broadened after acquiring an eclectic collection loaded with older art. Within a year of selling a major portion of the Duveen material at auction in 1971, Simon bought highly revered 16th and 17th century paintings, including Francisco de Zurbarán’s “Still Life With Lemons, Oranges and a Rose,” a jewel of the Pasadena museum. And although Simon subsequently became a serious collector of South and Southeast Asian art, his museum is probably best known for its Old Master works.

Suzanne Muchnic, a former Times staff writer, is the author of “Odd Man In: Norton Simon and the Pursuit of Culture.”

--------------------------------------

‘Lock, Stock and Barrel’

What: An exhibition on Norton Simon’s purchase of the Duveen Brothers Gallery

Where: Norton Simon Museum, 411 W. Colorado Blvd., Pasadena

When: Opens Oct. 24. Closed Tuesdays. Ends April 27.

Admission: $12

Info: (626) 449-6840, https://www.norton.simon.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.