Review: When refusing the hour saves the day

- Share via

When the celebrated South African artist William Kentridge created his installation “The Refusal of Time” for Documenta 13, the international exhibition in Kassel, Germany, five years ago, it proved such a draw that you had to refuse an hour or more to wait in line to see it. Through films, various contraptions, megaphones broadcasting competing soundtracks and off-kilter metronomes ticking time, Kentridge meant to show the unsuspected connection between the clock and colonialism.

The exhibition happened to be in a grungy corner of the Kassel train station. As we stood aimlessly in line that hot summer of 2012, commuters, regulated by trains running precisely to the clock, rushed by in obvious disregard for our refusal of the hour. With Documenta’s intentional reference to the station in World War II having been a transfer point for Jewish prisoners sent to concentration camps, clocks and trains took on sinister significance.

The result is that the refusing of an hour or two symbolized political import in a way that an installation piece created for this environment could never quite reproduce elsewhere. It lasts a half-hour and has traveled widely, but at nice museums in New York, San Francisco or Salzburg, you spend a few minutes with it and then move on to the next thing.

To fully refuse the hour might seem better the job of opera, and thus Kentridge turned “The Refusal of Time” into a chamber opera, “Refuse the Hour.” That show has, itself, toured the world over the last five years and the clock has now run out on it. The final performances were presented by the Center for the Art of Performance UCLA at Royce Hall on Friday and Saturday nights.

“Refuse the Hour” fills in many of the blanks in “The Refusal of Time.” It adds scientific, historical and political context. Kentridge himself delivered anecdotal talks about time and its consequences, an amiable, professorial emcee. He surrounded himself with fabulous dance; potent singing, operatic and otherwise (mostly otherwise); multidimensional video imagery; quirky music; even quirkier machinery on stage.

Clocks at UCLA on Friday night felt like they closed in on us in every media. Control time and you control the world. The arbitrary divisions of clock time are a Western invention, “Refuse the Hour,” boisterously demonstrates, handily allowing the overall coordination needed for the 19th-century colonization of Africa.

Calling “Refuse the Hour” opera might, itself, seem arbitrary, even though opera is Italian for “works,” and, if anything, this is theater as a display of works. Still, it is not opera in the sense that it is regulated by music. Philip Miller’s entertainingly offbeat, so to speak, score for a seven-member chamber ensemble — one that gives particular prominence to brass and especially the tuba — has the flavor of incidental music. Music, being the art of clock time, has here the idiosyncratic task of being an ironic advocate of opposing the clock.

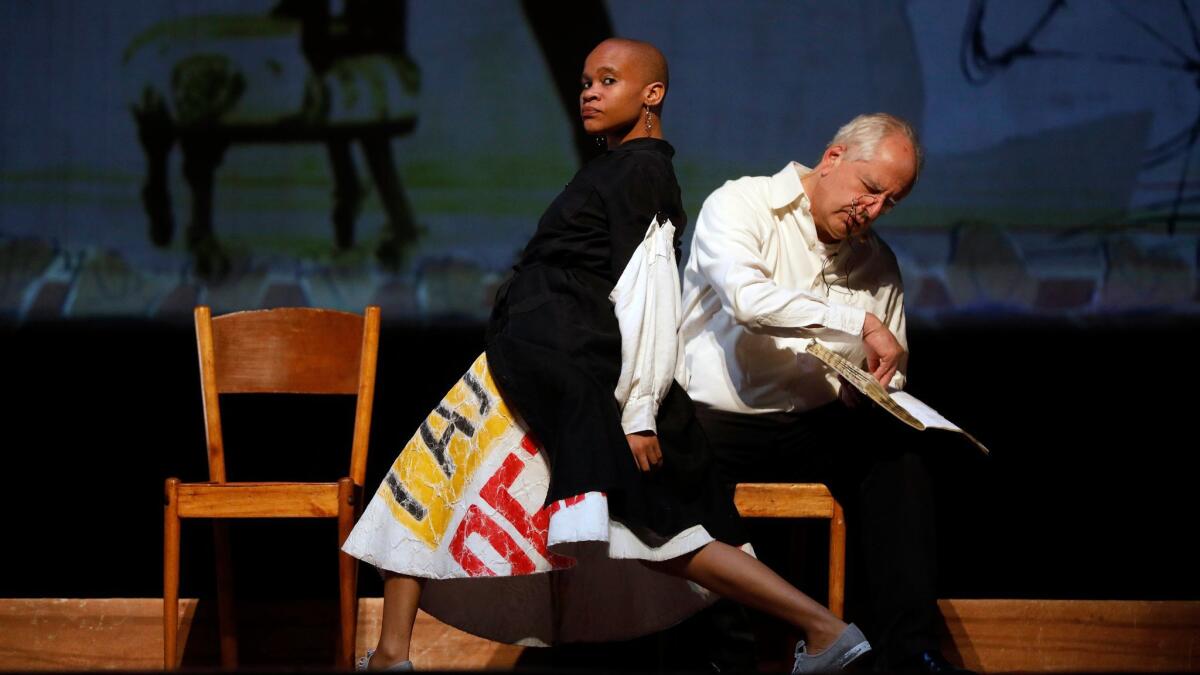

The opera is introduced with a rough-and-tumble construction of automated drums suspended above the stage, beating out-of-phrase rhythms of different drummers. The 62-year-old artist, dressed in white shirt and black slacks in contrast to others in spectacular African costumes, followed by recalling his childhood bewilderment over the myth of Perseus. How was it that every coincidence lined up in such an inconceivable methodical way that the ancient Greek hero would fulfill the prophecy of killing his father no matter every step taken to avoid it?

Perseus could not refuse his hour of fate. Can anyone? The dramaturgy of the production is credited to Peter Galison, a science historian. Time, we find, is more an idea than the heartbeat of the physical world. “Refuse the Hour,” which required an hour and a quarter to accomplish its task, was then meant to make this abstract concept of what it means for time to be malleable into something material.

That meant the application of layers. Layers are the essence of Kentridge’s work, whether drawing on old books transforming them into something else, or staging operas. For his new production of “Wozzeck” at the Salzburg Festival last summer, for instance, the stage seemed to become all of World War I happening at once, time again made meaningfully meaningless.

The layers of “Refuse the Hour” are found in the interaction of different aspects of theater, visual art, cinema, lecture and actual (well, maybe, sort of) opera. Much of the production’s overall character came from the vibrancy of South Africa, and particularly the extraordinary dancer Dada Masilo, who mirrored Kentridge’s purpose, in part, by becoming the manifestation of a supercharged elementary particle. The imposing singer Ann Masina stood on a balcony to turn Berlioz’s “The Specter of the Rose” into a song of haunting otherworldliness; she stood on stage for a more political purpose, a force of nature, singing in fervent protest.

The large video backdrop provided yet more layers of phantasmagorical imagery, old and new, sometimes so layered that old technology, such as giant metronomes, seemed as modern as particle accelerators. Was the singer, Joanna Dudley, with her bobbed haircut and curt stage presence, a cabaret singer from the past or the future? Either might have been possible.

Miller’s music, on the other hand, serves not to move action forward but simply startle. The one instrument not brass or percussion is what appears to be a Stroh violin, a rare, turn-of-the-20th-century fiddle with a megaphone attached.

Then again, megaphones are an obsession with Kentridge. He has all the modern amplification in the world (and the sound design in Royce, as were all production values, was brilliant), but everyone sooner or later tended to get his or her arms and/or legs on one of the many silver megaphones lying around on stage. They were even memorably used as artificial limbs for a Dada-like dance.

Kentridge also has a thing for processions, and as the hour passes in “Refuse the Hour” there was one on screen and another in the flesh, peculiar beings marching, each in his, her or its own time, to a perky, peculiar, brass-band-ish score. Kentridge’s parades move with an unknowable purpose — be it spiritual progress or protest march — but so persuasive you wish you could join in.

We’re left in the end with immortality. Kentridge explained the speed of light as being a comfort of nature. Everything that happens on Earth lives on. Peer at our planet from the vantage point of 500 light years away, and you can see a Renaissance artist at work.

Not even a black hole can take it all away, Kentridge has concluded. The celestial monstrosity absorbs all but a remnant of light, leaving a vague, distorted suggestion of what once was on the horizon of the black hole. “Refuse the Hour,” the opera, is, by the clock, no more. But it lives on in some form or other in a universe it taught us never to refuse.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.