Review: An artists’ look at citizenship and democracy in a world turned upside down

- Share via

Artists York Chang and Justin Cole have collaborated on a freewheeling exhibition that will continue to evolve over the course of seven weeks at Samuel Freeman in L.A.

The show “Constituent Parts” opened March 11 and will be reinstalled on Friday. It’s a fitting strategy for Chang and Cole’s stated purpose, which is to foster dialogues around notions of citizenship and democracy.

At least one piece seems to have changed since the show’s checklist was printed. Cole’s replica of Jack Ward’s sculptural monument to the Detroit riots of 1967 appears painted red and blue in the checklist photo. By the time I saw it, it had been painted black with a smattering of white on the top. You can read symbolism into either color scheme, whether that of political parties or racial groups.

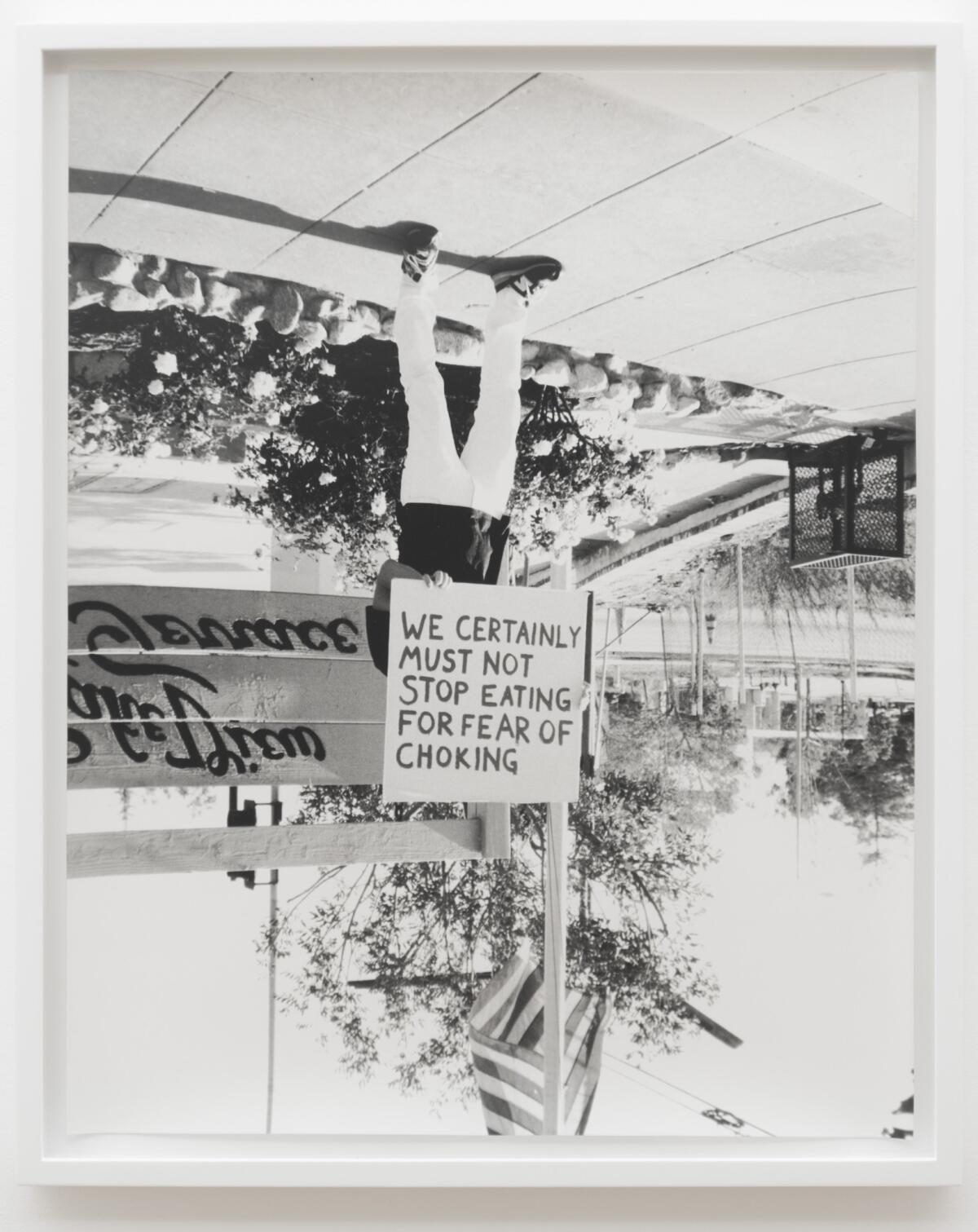

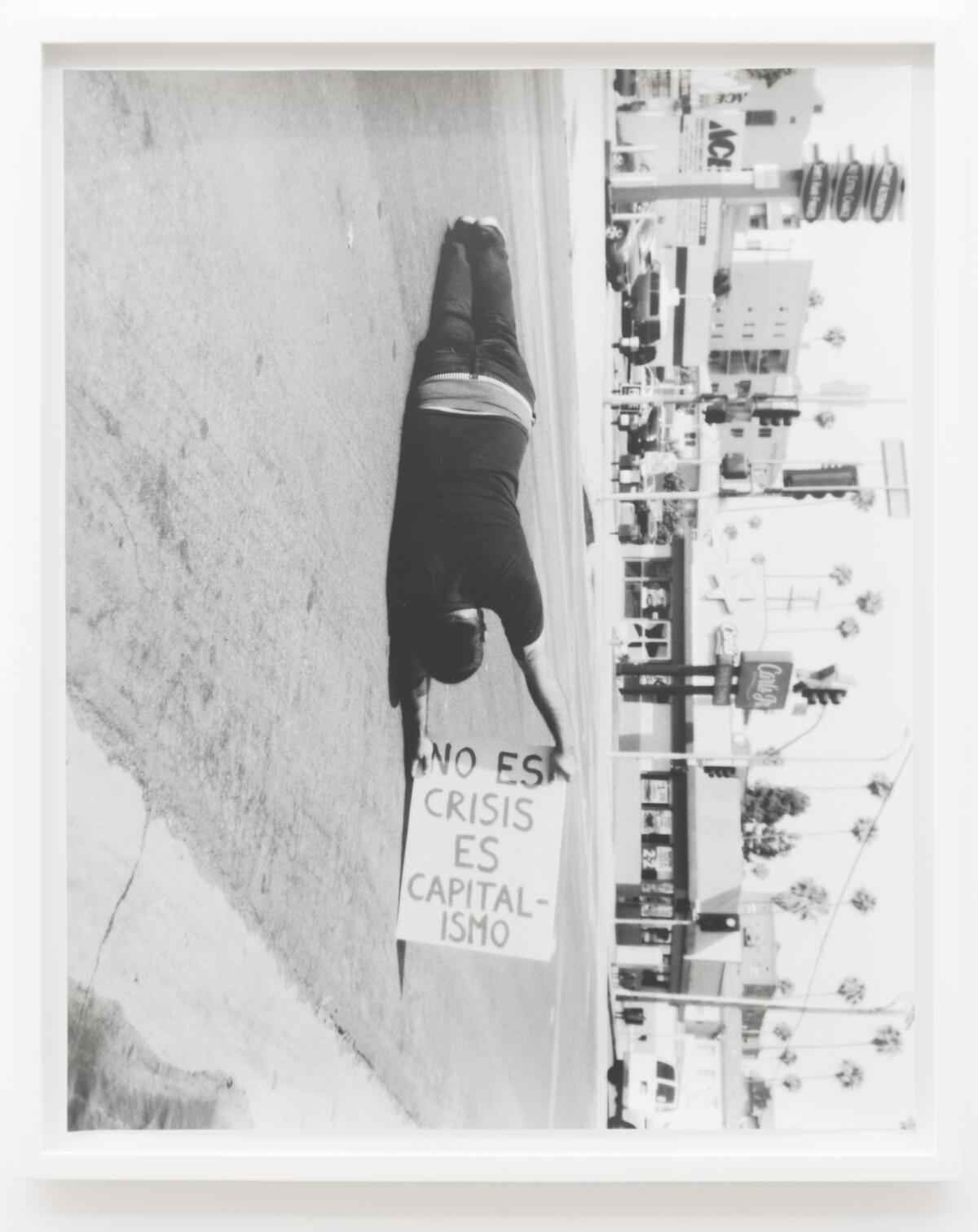

Cole’s contributions revolve around Detroit. The artist has also created — in addition to a photographic catalog of music-related sites and a kind of altar of Detroit books, records and souvenirs — a striking series of photographs of people holding protest signs. The photographs are displayed upside down or rotated 90 degrees, but the lettering on the signs is always right side up.

One such series reproduces the manifesto of Detroit’s White Panther Party, a 1960s anti-racist, free-love group. The others link the Detroit unrest to L.A.’s 1992 riots, capturing people at pivotal locations like Lakeview Terrace, where Rodney King was beaten by police. In these images the world is literally turned upside down or sideways, but the messages are always legible.

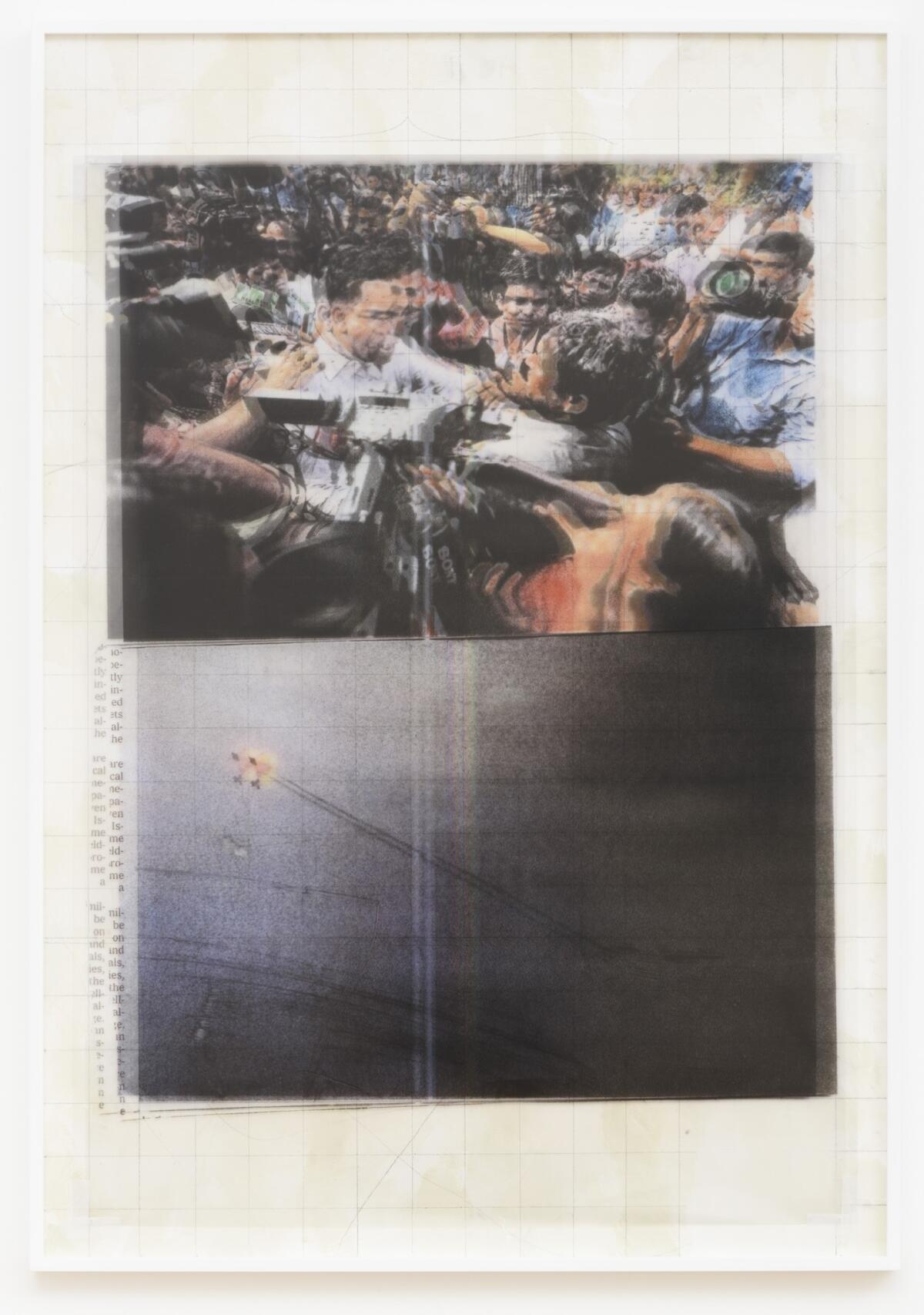

Chang’s contributions are more diffuse, also dealing with history and mass movements but through the lens of documentation. His “macrofiches” are blow-ups of portions of newspaper pages as they were captured on microfiche — that pre-digital, photographic technology for compressing large amounts of information into a small space. He leaves the distortions, warping and strange croppings in place, focusing on images of rallies and unrest, unmoored from historical specifics. Once made small, these images are resuscitated to loom large again.

More openly didactic is “Last Kiosk,” a plywood stage flanked by two panels facing each other. One depicts a crowd of brown men. The other depicts a crowd of white men and women in business attire. It’s a stark contrast and not at all subtle, but neither is the increasingly polarized world we navigate. Still, the piece is not about the panels, where the images are composed of cheap photocopies, easily torn down. It’s the empty space in between that counts, waiting for someone to take a stand.

Samuel Freeman, 2639 S. La Cienega Blvd., Los Angeles. Through April 29, closed Sundays and Mondays. (310) 425-8601, www.samuelfreeman.com

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

Auction battles and encounters with royalty: LACMA curator looks back at 24 years of adventures

With bold brush strokes and luminous neon, L.A. painter Mary Weatherford comes into her own

Doug Aitken's 'Mirage': a funhouse mirror for the age of social media

100 missing women: Drawings at African American museum tell a powerful story of loss

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.