Otto Heino dies at 94; master potter created ‘hearty and gutsy’ pieces

- Share via

Otto Heino, the Ojai-based master potter, educator and symbol of the midcentury California studio crafts movement who along with his late wife, Vivika, reformulated a lost-to-the-ages Chinese glaze that made him a multimillionaire, has died. He was 94.

Heino died Thursday of acute renal failure at Community Memorial Hospital in Ventura, said George Gemmingen, a friend.

The Finnish American Heino, who worked in collaboration with his wife until her death in 1995, earned an international reputation for robust yet beautiful wheel-thrown stoneware with artistically applied glazes that included glossy cobalt blues, silky reds and raspy earth tones.

In the mid-1990s, he became celebrated in Asia for a buttery yellow glaze that he and his wife had labored on for more than a decade. He claimed to have been offered millions for the formula but never sold it.

“Otto’s work is a wonderful blending of Scandinavian modernism and Japanese folk pottery,” said Jo Lauria, a coauthor of the ceramics book “Color and Fire” (2000). “He had a macho relationship with clay, and it was a badge of honor to be able to throw huge pieces, but they were always functional, emphasizing the sensuality of the glaze, the way in which it catches the light and invites you to touch it.”

Heino’s handmade vessels, which retain the ridges his fingers formed when shaping the clay, exhibit a style that was wholly his own.

Gerard O’Brien, owner of the Reform Gallery in Los Angeles, which sells the Heinos’ pieces, called the potter’s work “hearty and gutsy” and “ruggedly American.”

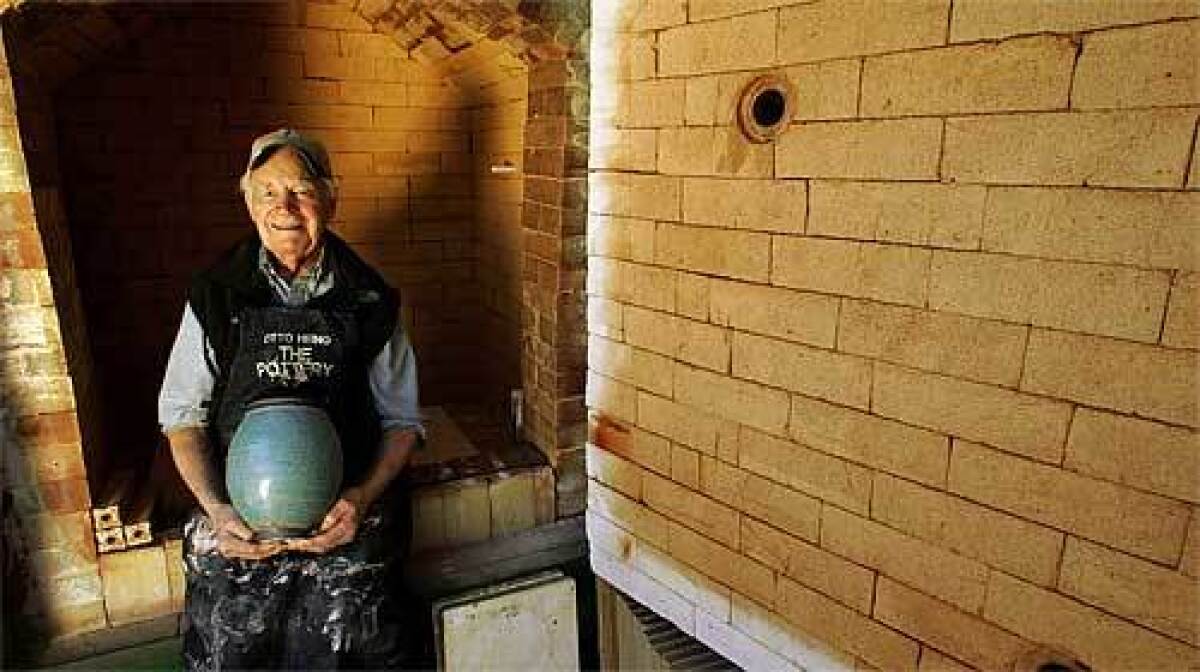

Still actively producing work for museums, international collectors and his home gallery until his death, Heino could throw 100-pound mounds of clay into 24-inch-wide platters. Without assistants or apprentices, he fired kilns of his own design, producing thousands of pieces a year. Those with the prized yellow glaze, popular during the Chin dynasty (AD 265 to 420), sold for $25,000 and up.

“I am the oldest, richest potter in the world,” Heino told The Times in a 2008 interview.

Though he indulged a passion for cars, purchasing a Rolls-Royce and a Bentley, Heino was also a philanthropist, donating his work and funds to ceramic institutions and the Ventura County Museum of History and Art, which staged exhibitions of his work in 1995 and 2005.

He was even more generous with his time, teaching, demonstrating and mentoring generations of potters from around the world.

Christy Johnson, director and curator of the American Museum of Ceramic Art in Pomona, said the Heinos “represented a time when the artist’s character was considered to be part of the beauty of their pieces. Their devotion to the work, to each other, and to teaching contributed to the fine quality of the work.”

Don Pilcher, a potter who studied under the Heinos at Chouinard Art Institute, said they were devoted to their craft and to passing along their knowledge as a legacy.

“They treated me, and others, like a son,” he wrote in an e-mail. “Watching Otto fire a kiln was a master class in care, precision and patience, I never saw anybody more reluctant to turn off a kiln. It was as if he were having an affair with the fire.”

Otto Heino was born April 20, 1915, in East Hampton, Conn., the fifth of 12 children of Finnish immigrants August and Lena Heino. He was raised on a New Hampshire farm where every child played a musical instrument; Otto’s was trombone. The large family survived the Great Depression raising dairy cattle and delivering milk. By the start of World War II, Heino had established a successful trucking business.

For five years, he served in the Army Air Forces as a fighter plane crew chief and a B-17 gunner.

During this time, he changed his Finnish first name, Aho, to Otto, which, along with his blond hair and blue eyes, helped him survive when he was twice shot down over Germany.

On a furlough in England, the war-weary hero visited the pottery studio of Bernard Leach, who had introduced Japanese techniques to British ceramics.

After observing the master at work, Gemmingen recalls, “Otto said, ‘If I live through this war I am going to dedicate myself to this.’ ”

After the war, Heino attended the League of New Hampshire Arts and Crafts on the GI Bill. He married his pottery instructor, Vivika Timeriasieff, in 1950.

Two years later, they moved to Los Angeles when she succeeded glazing master Glen Lukens in a teaching post at USC. Heino’s mechanical skills and education in ceramics helped him land a job with NASA working on rockets and space capsules.

In the mid-1950s, the couple lived and worked in a Victorian house on Hoover Street in Los Angeles.

“They opened a shop that sold only handmade pots and people told them they were crazy,” said O’Brien, “but they were successful and inspired other people to do crafts as a way of life.”

After a stint on the East Coast in the 1960s, the Heinos returned to California and purchased the Ojai home of a former student, acclaimed ceramist Beatrice Wood, and in 1973 established a gallery, The Pottery.

Heino earned the 1978 gold medal at the Sixth Biennial International de Ceramique in Vallauris, France, for a pot with two birds perched on the rim.

He and Vivika showed their work at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the American Craft Museum in New York, now called the Museum of Arts & Design.

Even after having a pacemaker installed in 2008, Heino remained indefatigable, telling The Times, “Never hurry, never worry. If you’re negative, you’ll never make it.”

The Pottery, which had been open to the public, has been closed.

Heino’s ashes are stored in one of the artist’s lidded jars decorated with one of his familiar birds and his renowned yellow glaze.

The Heinos had no children. Otto Heino is survived by his youngest sister, Olga Rogowski, of Canoga Park.

Memorial services are pending.

Donations may be made to Vivika and Otto Heino scholarship funds administered by Ojai Studio Artists, www.ojaistudioartists.org, or the League of New Hampshire Craftsmen, www.nhcrafts.org.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.