Review: Benjamin Millepied dances outside the ‘Framework’ at MOCA

- Share via

Who exactly is Benjamin Millepied as a choreographer?

Hard to tell. Lots of us have seen his forceful neoclassic inventions for actresses and their dance doubles in the film “Black Swan.” Before that, he showed Southern California audiences an astute, compassionate piece (in several versions) for and about Mikhail Baryshnikov. More recently, he unveiled three relentlessly frothy, unmusical showcases for the Ballet du Grand Théâtre de Genève.

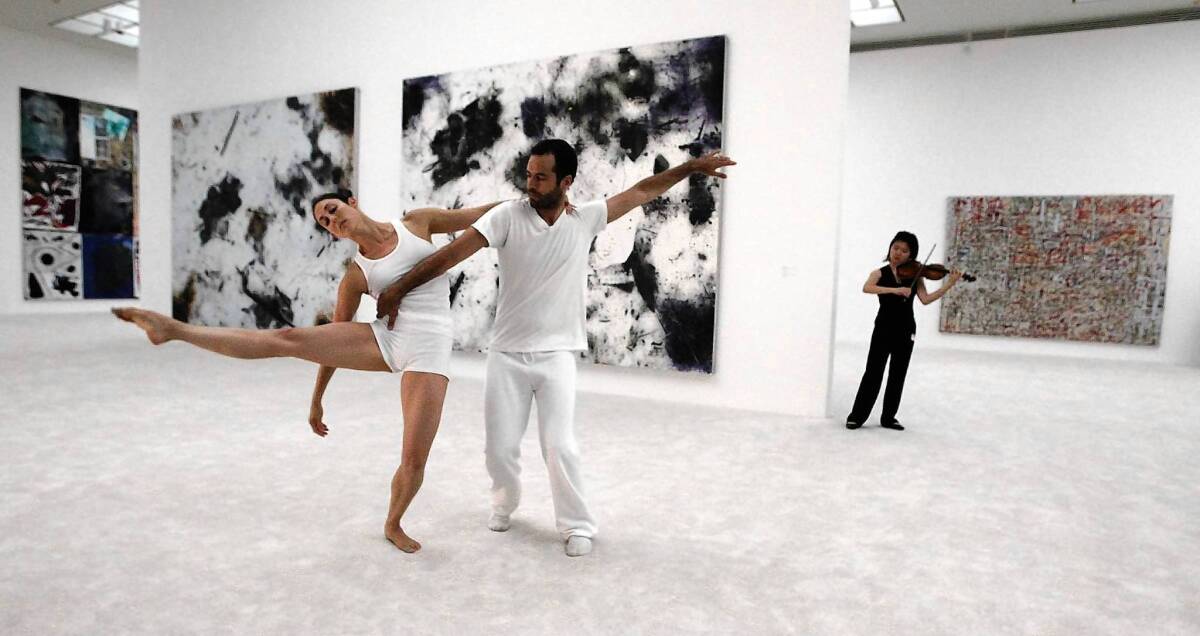

On Thursday, as a kind of fanfare for his upcoming L.A. Dance Project performances in Walt Disney Concert Hall — a September event that appears to have little “L.A.” about it except the funding — the transplanted Frenchman appeared in yet another guise. This time he cast himself as a free-form modernist, performing alongside dancer Amanda Wells and violinist Mayumi Kanagawa in a giddy, 25-minute gallery romp called “Framework” at the Museum of Contemporary Art downtown (and repeating twice in August).

The dancing began in the “Painting Factory” wing with a solo by Wells against a big, green, panoramic Warhol. Wearing a loose, sleeveless top and shorts, she was all restless, supple, undulating line in counterpoint to Kanagawa’s Bach while portable lighting units continually refocused her swirling lyricism. When the performance (and audience) moved to a room devoted to silver canvases by Rudolf Stingel, thoughtful recorded statements about art by painter Mark Bradford added another layer of texture.

Here Millepied soloed, wearing white pants and T-shirt. He’d danced with New York City Ballet, and in “Black Swan,” but not since, and not like this: wildly, compulsively, furiously, all about the Benjamin. Wells eventually joined him and they led everyone into the largest hall for a series of flashy, uneventful duets (no real connection or inspiration). At one point, they soloed on opposite sides of an enormous partition, and you couldn’t see both of them unless you stood along the edge of it — not an ideal vantage point.

They ended together, with more Bach, more playoffs between passages of ordinary walking steps and quick, dodgy, asymmetrical dancing, this time in front of two dynamic Bradford creations: “Untitled” and “Ghost and Stooges.”

No choreographic innovation here but a kind of imploding force-field generated by the dancers’ energy, the audience’s ever-changing proximity and the sense that if you really wanted to see this piece you had to become a part of it. And that revelation took root a little earlier when Bradford’s text spoke of fluidity and the way people enter and leave a space.

Right then, Millepied began diving into the crowd, making the public get out of his way, even colliding with his Music Center publicist and, above all, sculpting dance-space for himself wherever he wanted it — the gleam in his eye as bright as those solar flares we keep reading about. This is why his L.A. Dance Project exists: to take the city by storm. And at MOCA, Millepied looked like he might be the man to do it.

L.A. is a place where naked ambition gets you further than any other kind of nudity and Millepied obviously knows what works for him in France, New York, Geneva and now here. Contrary to his name, he may not have a thousand feet, just a thousand ways to move. And some of them can make even the audience dance to his tune.

Obviously, he got major applause. When there are no seats, a standing ovation is guaranteed.

ALSO:

Tony winner ‘Book of Mormon’ not a sellout

FBI recovers stolen Henri Matisse painting in Florida

MOCA director Jeffrey Deitch posts message, seeking to reassure

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.