The future of the Spanish language is looking a lot more like English

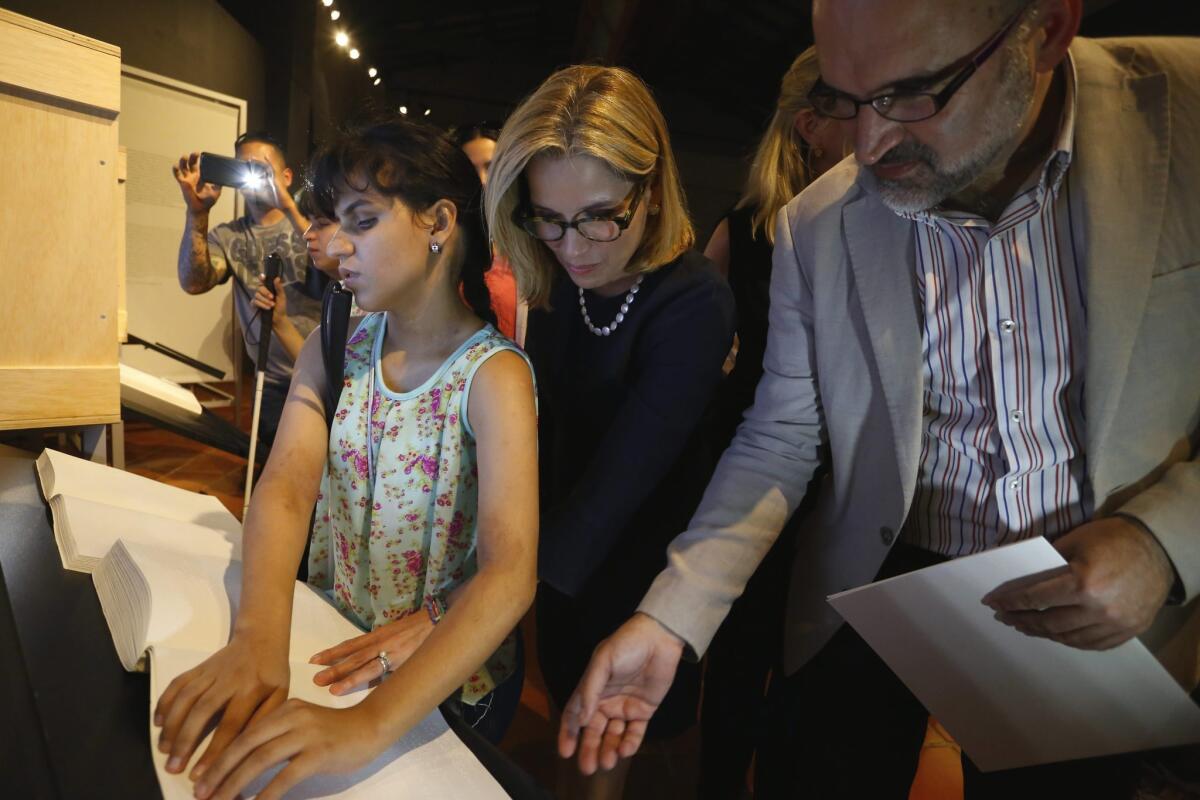

The mayor of San Juan, center, and José Manuel Lucía of the Spanish Royal Academy observe a woman reading the Spanish master work “Don Quixote” in Braille.

- Share via

More than 150 academics, novelists, poets, scientists and other experts of language have descended on San Juan, Puerto Rico, this week to debate the future of Spanish — and whether words such as “selfie” will be admitted into the prestigious Diccionario de la Real Academia (Dictionary of the Royal Academy — like the Oxford English Dictionary for the Spanish language).

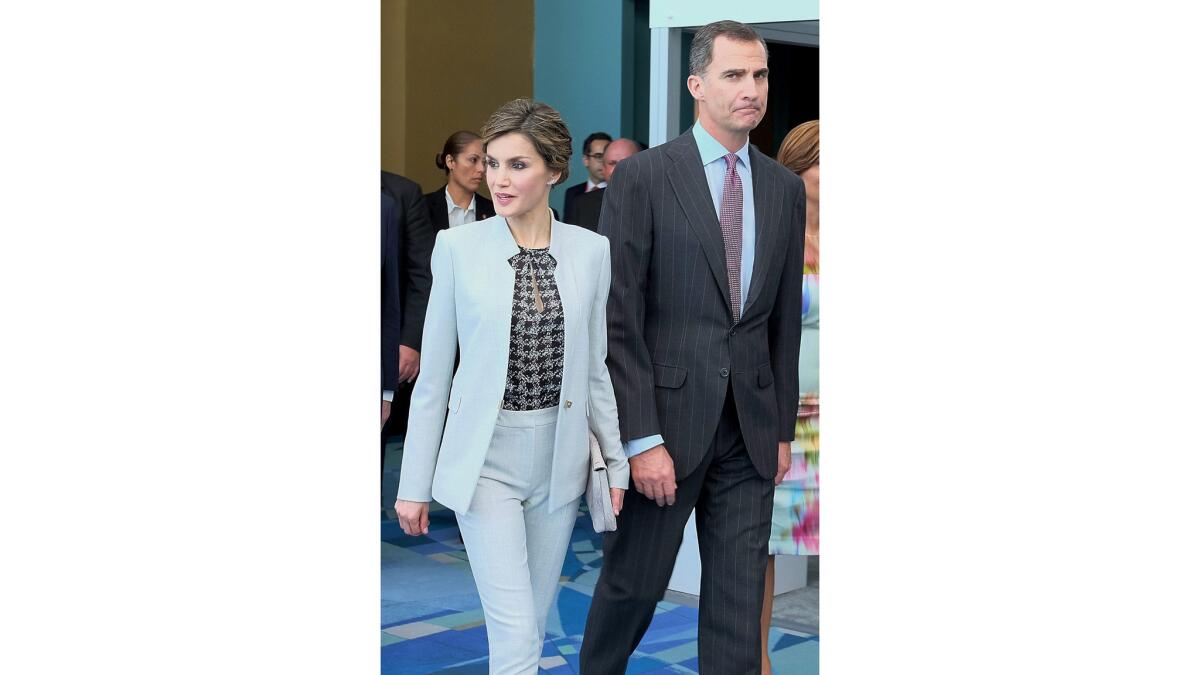

The confab, formally known as the VII International Congress for the Spanish Language, or CILE, includes among its attendees Chilean author Jorge Edwards, Puerto Rican essayist Luis Rafael Sánchez, Cuban crime novelist Leonardo Padura and King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia of Spain — along with various Latin American leaders.

Felipe VI of Spain, right, and Queen Letizia arrive for the VII International Congress of the Spanish Language in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Held every three years, it offers a whole lot of pomp and circumstance for what is essentially a conference about etymology. But it is indeed a fascinating one.

For one, Spanish is a language that unites roughly 500 million people around the world, including millions in the United States. Moreover, part of the role of these sessions, organized in part by the Real Academia Española (Royal Spanish Academy) in Madrid, is to find etymological common ground among vastly different peoples in vastly different corners of the globe — from Los Angeles to Tierra del Fuego to Malabo in Equatorial Guinea, where one of the official languages is Spanish.

And the academy, along with its partner institutions in Latin America, must do this at a time when English words have a growing profile within the Spanish language. The last time the Diccionario was issued, in 2014, it featured words such as “hacker,” “dron” (drone) and “tuitear” (to tweet).

It also, quite interestingly, included the words “bótox” and “pilates” — though, sadly, not the word “cuchibarbie,” a Colombian slang that refers to a woman who has had oodles of plastic surgery. Not to mention all of the other Spanglish slang that is part of daily life in a place like Los Angeles. In L.A., for example, you drive a “troca” (truck) to go “hanguear” (hang out) and “Googelear” the latest hot restaurants.

Like a lot of academies that stand as the guardians of language (see: the Academie Française), there is always some grumbling about Spanish tradition being lost to English slang when it comes to the inclusion of English root words in the dictionary. Dario Villanueva, who heads the academy, told the Associated Press that perhaps a better word for “selfie” might be the phrase “auto-foto.”

But David Pharies, an associate dean at the University of Florida and author of “A Brief History of the Spanish Language,” says these efforts at preservation can be futile.

“There is a long history of linguistic institutions such as the Spanish Royal Academy trying to ‘police’ their languages’ vocabularies or grammatical norms,” he stated via email. “In general, it can be affirmed that over the long term all such efforts are doomed to failure, since a subset of today’s innovations form the basis of tomorrow’s norms. ... Sooner or later, language guardians are forced to abandon conservative positions in the face of relentless changes in usage.”

In addition, Spanish, which is a descendant of Vulgar Latin — the informal, spoken versions of Latin that flourished in different parts of the Roman empire — already bears heavy traces of other tongues.

“Arabic contributed a number of words to the language as a result of the Muslim presence on the Iberian Peninsula from 711-1492,” Pharies writes. “Arabic did not affect the grammar of the Spanish, but its political presence had important historical effects that helped determine the nature of Spanish.”

Over the years, the Americas have contributed increasing numbers of words to the language and, as a result, the Royal Academy’s dictionary. (These days, less than 10% of the world’s Spanish speakers live in Spain, where the language originated.) Many of our continent’s contributions are drawn from indigenous words. “Tomate,” the Spanish word for tomato, for example, comes from “tomatl,” the Nahuatl (Aztec) word for the fruit.

The last time the Diccionario was published, it contained more than 28,000 words of American origin — double the amount it contained in the previous edition.

Already, the Royal Academy’s dictionary contains the popular Mexican slang “güey,” which literally means ox, but generally means “fool” — depending on context and intonation. And this week it added a new Latin Americanism to its pages: “puertorriqueñidad,” which translates roughly to “Puerto Rican-ness.”

So far, however, the more Anglicized “Nuyorican” (New Yorker of Puerto Rican roots) remains off the books. That, however, may just be a matter of time.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.