Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute, the building that guesses tomorrow, is aging — very, very gracefully

- Share via

The U.S. may not have awe-inducing ancient temples of the sort you see in Athens, Rome or Mexico City, but we have produced modern ones. Foremost among them: the Salk Institute in La Jolla.

Perched dramatically on a hillside above the roaring Pacific Ocean, the nonprofit research complex, completed in 1965, was designed by Modernist architect Louis Kahn. His symmetrical, saw-tooth arrangement of brut concrete buildings frames a brilliant travertine plaza devised by Mexican architect Luis Barragán. The entire composition feels like entering a procession — one that dissolves in an endpoint where ocean meets sky.

Its function may be for science, but Kahn’s structures feel more like a temple to nature. Walk across the plaza, bisected by a gurgling channel of water, and it will come as little surprise that over the course of its life, the Salk has been been hailed as “San Diego’s anonymous Taj Mahal.”

Anonymous because even though it is an icon of Modern architecture, it maintains a relatively low profile: Invisible from the street, only revealing itself once you enter the Salk campus, it’s the sort of place that isn’t stumbled upon. You have to seek it out.

“I go there practically every time I’m in San Diego,” says Annabelle Selldorf, the New York-based architect who is designing the renovation and expansion for the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego in La Jolla. “It reflects an understanding of science and the simultaneity of working together and working in solitude. It reflects our desire to be in contact with nature, but also a very refined thinking about tactility and materials. I find it so inspiring.”

Not only do the buildings continue to function well, I would say this is the best way to build a laboratory.

— Thomas Albright, neurobiologist at the Salk Institute

It has been a little more than 50 years since Kahn completed the task set before him by his client, Dr. Jonas Salk, developer of the first successful polio vaccine, to “create a facility worthy of a visit by Picasso.”

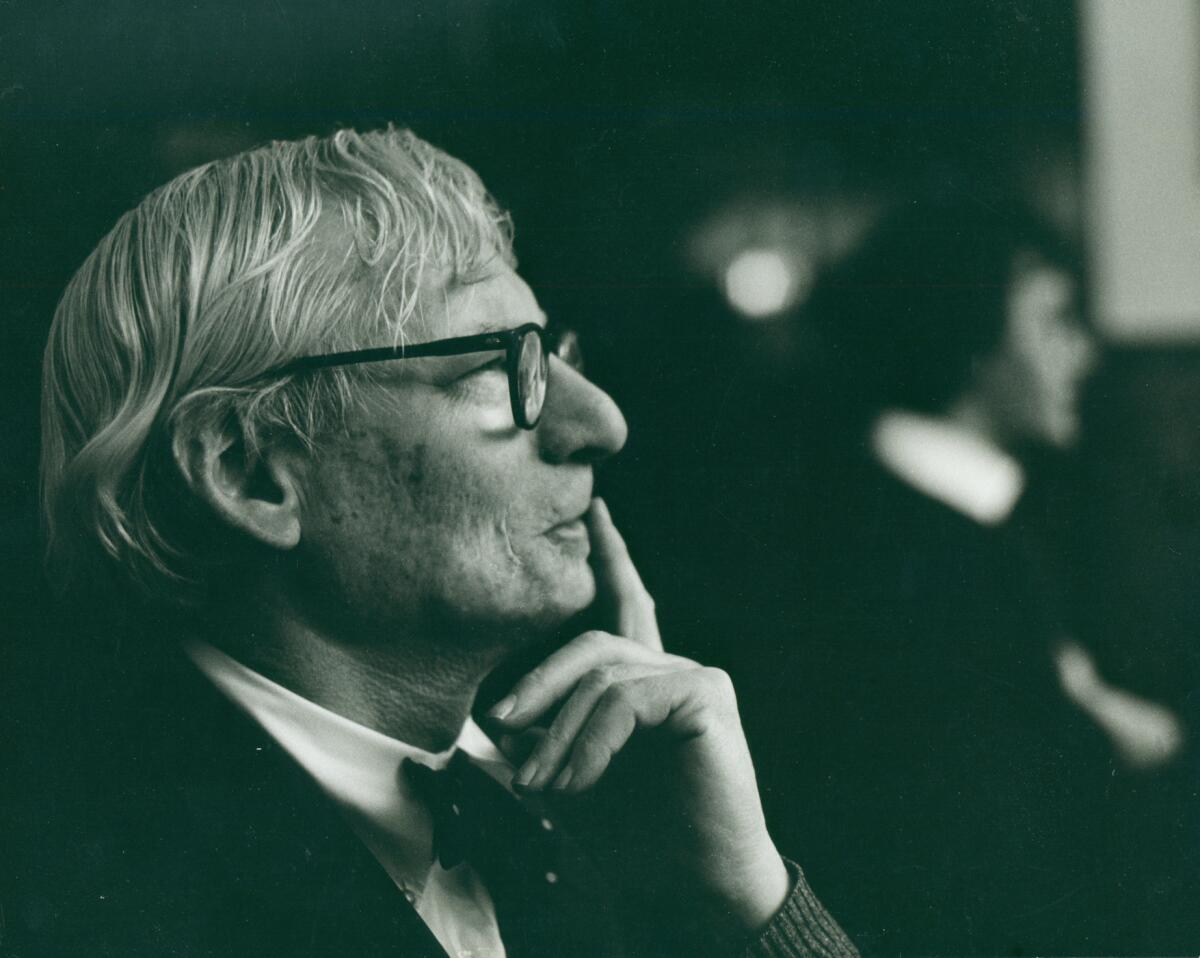

Earlier this month, the San Diego Museum of Art debuted a sprawling exhibition devoted to Kahn, one of the 20th century’s most influential designers. “Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture” — organized by the Vitra Museum in Germany in collaboration with the Architectural Archives at the University of Pennsylvania (which holds Kahn’s papers) and the New Institute, a design museum in the Netherlands — features drawings, models, photography and video from throughout the architect’s career. This includes original drawings and models depicting facets of the Salk.

READ: Christopher Hawthorne's review of “Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture” »

The confluence of events makes it a fine time to evaluate how the Salk, Kahn’s masterpiece in our midst, is holding up — both in terms of design and the materials from which it is made.

“It’s at the 50-year mark,” says Sara Lardinois, a project specialist at the Getty Conservation Institute, “which is when most Modern buildings are ready for their first major repair job.”

The top line? The Salk is entering its grande dame period with panache. And while it is certainly showing signs of its age — some wear on the teak wood elements, a bit of spalling on the concrete — it nonetheless continues to function nimbly as an important scientific research laboratory. (One that has harbored half a dozen Nobel laureates over the course of its life.)

“Not only do the buildings continue to function well, I would say this is the best way to build a laboratory building,” says Thomas Albright, a neurobiologist who has worked at the Salk for three decades.

“It’s a facility that has aged well and gracefully,” adds Tim Ball, who serves as the senior director of facilities at the complex. “Its flexibility still allows creativity and advancement in science.”

This grace has everything to do with Kahn’s thoughtful design more than a half century ago.

The architect, who was born in Estonia, but lived in Philadelphia for most of his life, had already established a name for himself when he accepted the job from Salk in the late 1950s. At that point, he had already received the commission to build the Richards Medical Research Laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania — a building that served as an important precursor to the Salk and earned him a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In Salk, Kahn found not just a client, but an important intellectual partner — one who wanted to create an advanced laboratory that would employ architecture that was just as advanced.

“There was a reason he had such a fruitful relationship with Salk,” says curator Ariel Plotek, who oversaw the installation of the Kahn exhibition. “There was the fact that that they were both Jews from [the former Russian empire] — Salk from Russia and Kahn from Estonia. Kahn also had a real interest in science. That is something you see in his other work as well, like the helix pattern for the City Tower he designed for Philadelphia.” (A structure that was never built.)

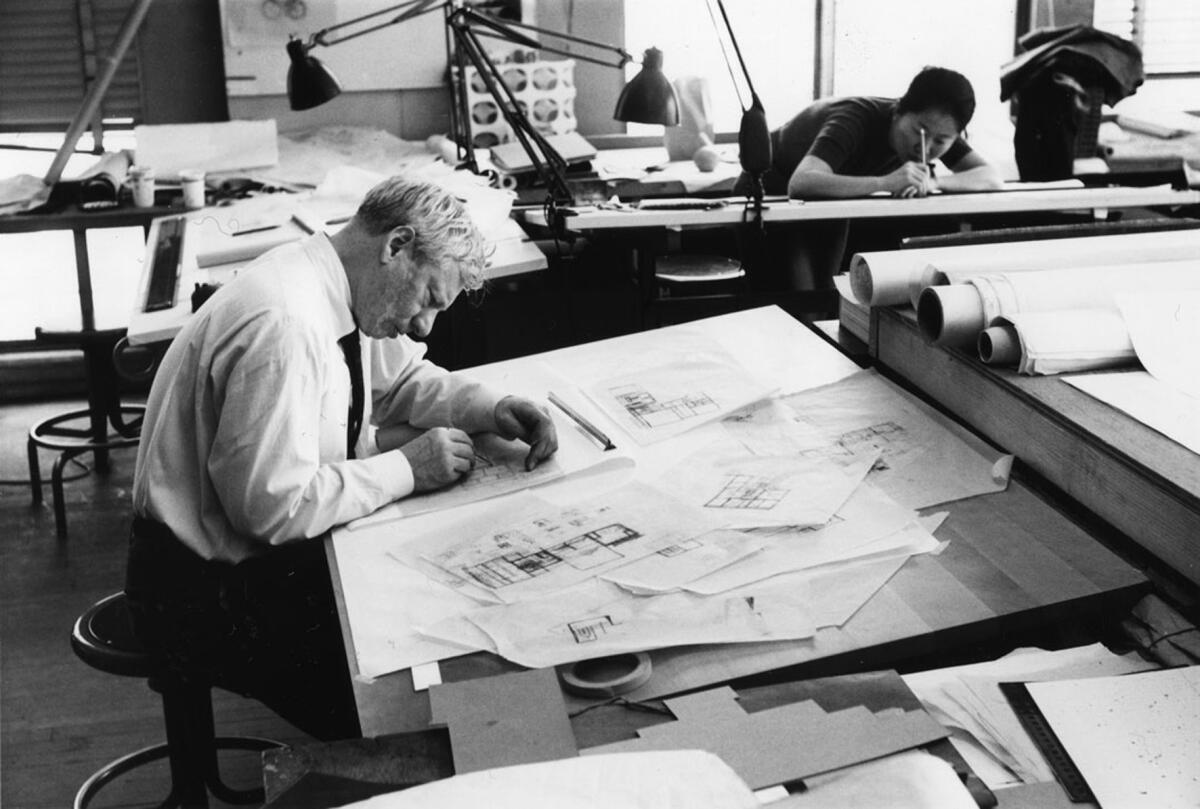

At the Salk, the architect employed a key idea he had begun to develop at the Richards in Philadelphia: Separating the floors that contained the laboratories from the ones that contained utilities such as electricity and ventilation, meant building maintenance at the Richards could be done without disturbing the science.

Flexible touches at the Salk include placing some mechanical systems behind easier-to-access block walls instead of the more architectural poured concrete. Lab windows can be easily unscrewed to allow for the introduction of oversize equipment. And, most significantly, support beams are placed at the perimeter of the 245-foot-long laboratories, so these massive spaces can be configured and reconfigured in different ways over time.

Kahn also corrected some of the problems that had plagued the Richards, such as crowded laboratories and a lack of private space.

“What’s truly amazing is the thought that went into the construction,” says Ball. “The way they built it makes it very easy for us to adapt to advances in science.”

Albright, who oversees the Salk’s Center for the Neurobiology of Vision, and studies the ways in which the brain perceives things, including architecture, says the open lab plan makes for a more dynamic place in which to study science.

"My lab flows into the lab next to me and that’s the valuable thing,” he says. “The sparks fly at the boundaries of different areas of scientific research. People are always running into other people.”

The open design also means it is possible for scientists to continuously update their equipment and reconfigure their spaces without having to tear into walls or rebuild floors.

As Salk told architecture writer Esther McCoy in 1967: “The building does guess tomorrow. The obsolescence is reduced by the investment in flexibility.”

This makes the Salk Institute very contemporary. These ideas — about creating flexible space that can be adapted over time — preoccupy today’s architects as they consider issues of sustainability. Likewise, there is the use of abundant daylight, which reaches even the basement levels of the building through a series of open-air courtyards and light wells.

“The way the light penetrates it, it reaches all the way down,” says Ball, “you can turn off all the lights and still have daylight in the building.”

The one area of the institute that has needed work is the teak wood panels that line the private study areas of the building, and soften the brutal nature of the Kahn’s raw concrete. These have contended with termites and been weathered by the sun and La Jolla’s salt air. Plus, a spore that likely comes from area eucalyptus trees was turning the wood black.

“In some cases,” says Ball, “we had ¼ to ½ an inch of wood loss from the weathering.”

The Salk is currently in the midst of a $9.7 million restoration plan to fix the teak and study other fixes with the assistance of the Getty Foundation and the Getty Conservation Institute, which have supplied research funds and expertise.

Lardinois has spent time digging around the architect’s archives at the University of Pennsylvania, and interviewing former associates to understand the architect’s approach to the wood. (Kahn died in 1974.) “They are a unique synthesis of industry and craft,” she explains of the teak fixtures. “They were made in a cabinet maker’s shop.”

The conservation plan will help preserve much of the original teak (roughly 70%), which will be supplemented with new panels — all of which are being treated with fungicide and a UV coating that will not affect the wood’s look. Already, tests have been conducted and work on two of the complex’s study towers have been completed. (Though if you are thinking of visiting, it’s best to hold off until March, when the black construction scaffolding that now envelopes most of the complex comes off.)

Beyond their flexibility, the buildings embody other contemporary ideas, too. The entire complex is based on important notions of collaboration. In this case, it was the unique partnership between Kahn, who designed the building, and Barragán, who developed the plaza’s iconic look.

Kahn had been thinking of planting trees between his two rows of laboratories. It was Barragán who told him, “I would put not a single tree in this area. I would make a plaza. If you make a plaza, you will have another facade to the sky.”

“There is this myth of the great lone architect in isolation who conceives a great master work,” says Selldorf. “But the Salk is a great master work because it was placed in context and contact with others. It comes as a result of dialogue and collaboration and conversation.”

His buildings have a conviction about how you bring people together.

— Annabelle Selldorf, architect

It’s a collaboration that draws architectural pilgrims from all over the world. (The building receives an estimated 4,500 visitors a year.)

Plotek first saw the Salk Institute on a trip to California in the early 2000s, before he had moved to the area. “I felt I was in the presence of something that was as perfectly designed and as sublime as the religious buildings I had studied,” he says. “There is a wholeness to it, a unity.”

Architecture writer Sam Lubell, who included it as one of the top sites in the newly published guide “Mid-Century Modern Architecture Travel Guide,” says the comparison to the Taj Mahal holds up.

“It’s perfectly symmetrical and you have this channel that leads to infinity and you get this feeling of awe,” he says. “I like to call it the Taj Mahal of Brutalism. I’ve been to the actual Taj Mahal a couple of times, and it’s the same feeling: You get pulled in every time you are there, staring down that long channel.”

“And of course, there’s the site, which is right on the edge of the Pacific Ocean,” he adds. “It’s very experiential. A lot of Louis Kahn’s work is like that. You don’t get it until you go.”

But, above all, are the myriad human touches: Offices are purposely disconnected from studies, requiring researchers to step into fresh air. Conversation areas are located throughout, encouraging scientists to gather and exchange ideas. Warm, wood-lined studies, with views of the ocean, offer areas of intense contemplation.

“We think about Kahn because of his use of material,” says Selldorf. “But I find myself returning to Kahn a lot these days because of the very unequivocal moves he makes. His buildings have a conviction about how you bring people together.”

It is indeed a temple of sorts — to science, to people, to the sky and sea for which California is so well known. And it’s destined to be with us for many more years.

+++

For details on visiting the Salk Institute, along with information about regular weekday tours, visit salk.edu.

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

ALSO

Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego marks 75 years with launch of bold expansion plan

George Lucas' museum designs for L.A. and S.F.: A first look at competing plans

From UC Davis to the National Mall: Key architecture projects this fall

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.