Q&A: ‘He Named Me Malala’ filmmaker wanted to go beyond the headlines and get a message to girls

The relationship between Nobel Peace Prize laureate Malala Yousafzai, from left, and her father, Ziauddin Yousafzai, is the focus of documentarian Davis Guggenheim’s “He Named Me Malala.”

- Share via

Oscar-winning documentarian Davis Guggenheim’s (“An Inconvenient Truth”) newest film, “He Named Me Malala,” showcases Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani teen who was shot in the head by the Taliban for advocating education for girls. She survived and went on to share a Nobel Peace Prize two years later.

As a subject, Yousafzai possesses that irresistible combination: extreme courage in the face of violent hatred and preternatural oratorical presence. After spending nearly two years filming the now-18-year-old, Guggenheim says Yousafzai — who is particularly close to her father, Ziauddin Yousafzai, who is also featured in the film — is the ultimate “role model for how I’d like to live life. I’m continually astounded by her presence, intelligence and character.”

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

Given the renown and glow of your subject, what were your major concerns going into the project?

The challenge for me always is how do I find my way into the story? The fact that a lot of people knew Malala was a girl who was shot on her school bus, etc. — I didn’t want to repeat what we already knew. When I was first asked to do the movie, I immediately flashed onto this father-daughter angle; I wanted to crack that mystery: What is it about this father and this daughter? That was my first way in.

You also kept much of the surrounding political turmoil in her story subdued. Why?

That was a conscious choice. And we’ve had some criticism about not explaining the rise of the Taliban and the surrounding geopolitical scene, but I felt that it was a burden. The book [“I Am Malala”] with [veteran British journalist] Christina Lamb — who is an expert in the region — had a lot of that information, but to me as a filmmaker, it was this idea of building toward a choice; a girl deciding to risk her life to speak out for what she believes in. To me, that was the center. It was epic, and I wanted to focus on that. And I felt if I focused on the larger geopolitics it would just swallow that up.

When I saw the film, there were rows filled with young girls. Is this the imagined audience you were trying to reach?

I hear that and it makes me happy. When I make a film I try and imagine a very specific audience. For [“An Inconvenient Truth”], for example, I imagined my Republican cousins in Ohio — I mean what’s the point of convincing lefties in Santa Monica about climate change? I want to challenge people. So my original thought was: What if a 13-year-old girl brought her father to the film? That’s who I imagined. And so it’s just another reason not to focus on the complex geopolitical message. A girl can see this and say, that’s my story; it’s the human story.

Like my daughter this morning: There’s a screening tonight and she asked if she could come, and she’s seen it a couple of times already. Now, none of my kids ever ask, they never want to see any of my movies. [laughs]

A girl can see this and say, that’s my story; it’s the human story.

— Davis Guggenheim, ‘Malala’ director

It’s astounding to see how confident Malala is. You’ve said when she went to see President Obama and confronted him about the drone strikes, she wasn’t even nervous. How is that even possible?

Yes, she has a poise and confidence that even very few adults in these situations aspire to. The only way I can explain it is that she came so close to dying; she met death and that left her so deeply focused, all the other just falls away.

She does say often, that “weakness, fear, hopelessness died; strength, power and courage was born.”

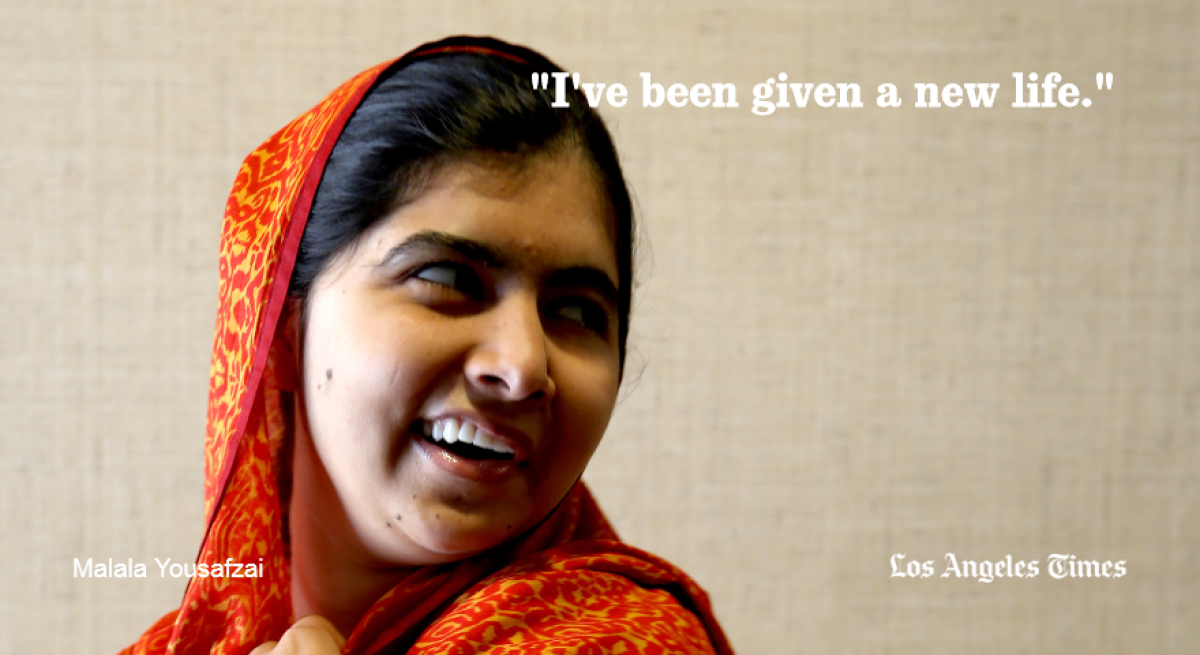

In the movie, there’s a moment — and I remember being with her when she said it, it was very moving. An interviewer asked her, “Why do you do this?” And she said, “I’ve been given a new life.” And that’s very profound and true.

The animation for some scenes was beautiful. What were the difficulties and challenges mixing two such different modalities?

The process of making documentary and the process of making animation are completely opposite. Especially regarding when you need to make decisions — for documentaries you can kind of move things around, even on the last day. The structure, adding shots, choosing dialogue … but with animation, because it’s so time-consuming, you fight for every frame.

I decided to build an animation company here in my Venice office. We had something like 15 people working on animation on computers; on one side of my office I’d be doing my thing and the other side would be doing the exact opposite. It was a real challenge. And the story structure itself didn’t really get clear until the last two months of shooting.

What changed?

Great editors. We’d try and fail and try and fail. The film itself was all really different in terms of timeline [before Malala being shot and after] and with the animation, it was difficult to put together.

What did Malala think of it — did she see it early on?

The first time they saw it [at a private screening in Birmingham, England, where the Yousafzais currently live], they didn’t know what to think. They were kind of giggling in parts — I mean imagine seeing yourself up on film and then imagine being from Pakistan and seeing yourself in a film — it was a shock.

Is she more comfortable with it now?

They were both very respectful of me; they deferred to me a lot. And yet they had some really insightful thoughts about how Islam was being portrayed that my team, as Westerners, didn’t pick up. Subtleties. It led to some key moments. There’s a great line in the movie — it was actually taken from an interview done after Malala had seen the movie: The Taliban “weren’t about faith, they were about power.” On the radio broadcasts [heard in the film], the Taliban were speaking as if they were true believers and they wanted that distinction made. And if that subtlety hadn’t have been made clearer, boy, it would have been a big mistake.

Considering your stated intentions for the film to be an inspirational call-to-action for young girls, can big phenomenal movements surrounding a film — i.e. what occurred with “An Inconvenient Truth” — be manufactured or are they just spontaneous explosions?

That’s a good question. You can help create but, frankly, that movie caught a wave, right? You can help it catch that wave. And for “Malala,” there’s already a large group of people deeply passionate about girls’ education. And the more it plays, it stokes that fire. It’s not a blockbuster, but I was downtown at a screening for 6,000 disadvantaged public school girls, mostly Latino and African American, and you could hear a pin drop. Cheering, a standing ovation at the end. The hope is that it carries for a very long time. That’s my hope, and that’s my measure of success: that it lives in the minds of girls.

ALSO:

Director Khalik Allah’s documentary captures beauty at a Harlem intersection

The ‘Ishtar’ effect: When a film flops and its female director never works again

Laurie Anderson’s quirky brain, in life and on film

More to Read

Sign up for The Envelope

Get exclusive awards season news, in-depth interviews and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.