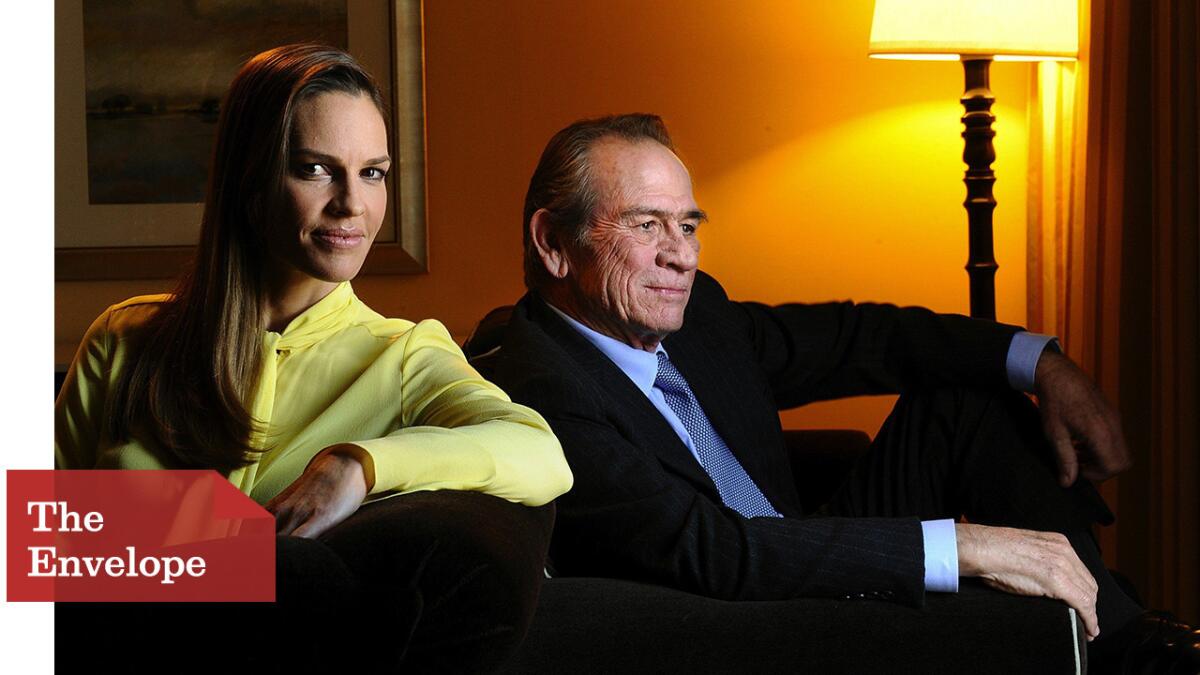

The Envelope: Tommy Lee Jones, Hilary Swank admire the feminism in ‘Homesman’ western

- Share via

To which part of calling “The Homesman” a “feminist western” would Tommy Lee Jones, its director, co-writer, co-producer and costar, be more likely to object?

“It’s not very meaningful,” says Jones wearily. “I know what a western is; it’s a movie that’s got horses and big hats in it.”

“And usually just men,” adds costar Hilary Swank.

“The women are usually whores with Technicolor hair and hearts of gold,” scoffs Jones, Swank nodding in assent. “There are also those who stand at the stove in their aprons and wring their hands and bring coffee.”

Jones prefers to look at the film, adapted from the novel by Glendon Swarthout, as historical fiction. Yes, there are big hats and horses, but it’s a rare narrative of America’s pioneer days that seriously considers women. Jones has said by looking at the condition of women then, one can see the roots of their condition today.

“I don’t think there’s a woman” among the readership of this newspaper, says Jones, “who has not at one time been objectified or trivialized because of their gender.”

“That’s 100% true, and that’s what makes it timeless,” says Swank. “It takes place in the mid-1800s, and we’re in 2014 and it’s still timely.”

It may come as a surprise to most readers that such a thing as a “homesman” existed — a person charged with returning settlers incapable of fending for themselves out on the frontier back to their places of origin. In the film, three women have been driven mad by the hardscrabble life and the brutal experiences specific to their gender. None of the men, including their husbands, will undertake the long, dangerous journey. Strong-willed, independent Mary Bee Cuddy (Swank) steps up, aided by a claim-jumping rogue who gives the name George Briggs (Jones).

“I’d never heard of a homesman, but my dad showed me an account of our history — my family is from Iowa, I was born in Nebraska, I come from farmers,” says Swank. “I didn’t see this until after filming, because my dad didn’t know what the movie was about. It directly paralleled this. My jaw dropped.

“I read it three days ago, my family history. I knew it was a dangerous, dangerous time, but the resiliency of these people was profound. There was no help for people with mental illness at that time. It was no less prevalent; we just have ways of dealing with it.”

The two-time Oscar winner may come from farmers, but she was no horsewoman coming in.

“She worked all day long,” says Oscar winner Jones. “She didn’t know a lot about horses or mules or wagons. She worked at it until she was able to present an inarguably convincing image. When most actors, certainly most actresses, would be heading to their trailer, she would go to her horse and take off.”

That dedication was particularly notable because of the sometimes unforgiving weather on location.

“In New Mexico, they say it’s four seasons in one day; I added a fifth: wind,” says Swank with a grin.

“It got cold. And wet. And windy,” says Jones.

After a beat, Swank picks up the ball: “It definitely infused the underlying challenges of what these people were experiencing, but then we got to go home at night and have a hot bath and a warm bed and a nice meal to keep us sane. But it definitely infused our understanding of what drove them to feel unstable.”

It was Jones’ friend, previous collaborator and eventual co-producer on “Homesman,” Michael Fitzgerald, who sent him Swarthout’s novel.

“I read it and thought there was a chance to make a screenplay of that book that had some originality to it,” says Jones. “And since our lives as filmmakers are a never-ending quest for originality, it was hard to pass it up.”

Swank says the script Jones co-adapted “was unlike anything I’d read. But also, it was a beautifully written, strong, multifaceted role for me. And there were other roles for women as well. It was a feminist movie in my mind. I jumped at the chance.”

Cuddy and Briggs come with unexpected layers. Their actions can seem initially surprising but make sense on closer inspection. “This is a woman who has values and morals and manners,” says Swank, “all things I feel like we’ve lost touch with as a society. She wants to do the right thing for the sake of doing the right thing. And I love that about her.”

Cuddy is no one-dimensional goody-two-shoes, however. A well of loneliness and despair informs her courage. Briggs can seem like a fool, but there is not only competence but real darkness beneath the devil-may-care surface.

Jones says the most appealing part of playing Briggs, though, was that “the part was available.”

Swank laughs at his deadpan, then Jones adds, “The character is a complete one in terms of this long journey. I was interested in that as a form, and a character that changes. That’s the way that form works. You have a long journey, and characters learn something about themselves, or fail to. And the viewer or the reader hopefully experiences an improvement of their time.”

One thing that has clearly improved over time is the treatment of mental illness.

“The 19th century treatment for schizophrenia was ice water,” Jones says. “People would be stripped naked and walked out in the snow and made to stand under pouring ice water, then put in a gown that had been soaked in ice water and put onto a cot and wrapped in blankets that had been soaked in ice water. After a few hours of that, they’d be gotten up and led outside and walked around again.

“Those were not the good old days.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Envelope

Get exclusive awards season news, in-depth interviews and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.