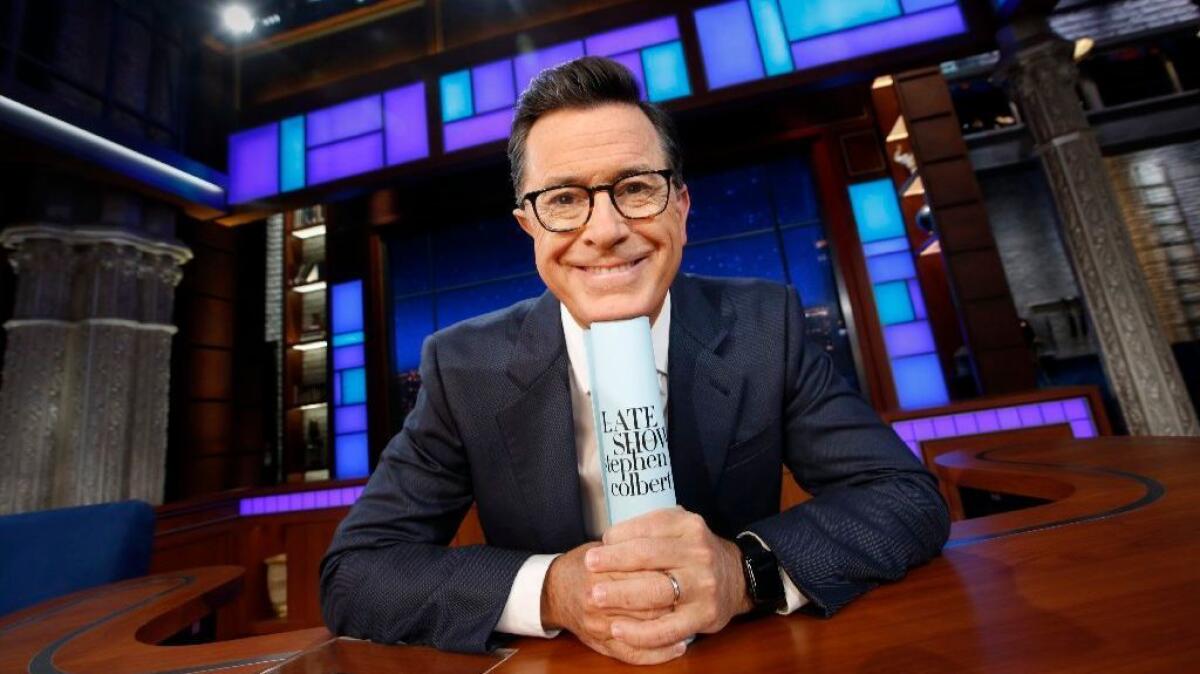

Q&A: Stephen Colbert on ideas that ‘could kill us all’ and the moment that changed his life

Stephen Colbert has little to worry about these days. (Aug. 17, 2017)

- Share via

When not in use, Colbert’s computer screen defaults to a live feed of the Earth taken from the International Space Station. Right now, the view has just crossed the Nile, the sun is setting and clouds are casting long shadows across the Red Sea. Colbert looks at these images whenever he’s feeling anxious. There’s the whole world, he tells himself. Calm down.

Professionally, at least, Colbert has little reason for worry these days. “The Late Show With Stephen Colbert” has reigned as late-night’s top program since February, and the recent “Russia Week” segments featuring Colbert visiting Moscow and St. Petersburg drew nearly half a million more viewers than its closest competitor, “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon.”

It’s a remarkable reversal for Colbert, who’ll be the first to admit that he stumbled out of the gate when “The Late Show” debuted on CBS in September 2015. “I was not indulging my own instincts, I’ll tell you that,” Colbert says.

That’s no longer the case. Colbert’s blistering broadsides against

Colbert, host of this year’s Emmys, took a break on a recent morning from preparing the show to talk about the trials and triumphs of the last two years. News alerts on his watch pinged a handful of times — the Senate was moving on healthcare — and Colbert, a focused man given to staying in the moment, fought against the distraction.

“But you have to look,” he says, glancing at his watch, apologizing. “We add new material between 4:45 and 5:15 almost every night. [The show tapes around 5:30 p.m. Eastern time.] We don’t want to wait until tomorrow. There’s an urgency now. We don’t want to leave anything on the vine for the next day.”

There were a few stories this spring with a variation of the same headline: How Stephen Colbert Got His Groove Back. Were you aware that you’d lost your groove?

I don’t know why I thought going from one show to the other and trying to change forms wouldn’t be difficult and painful. But I had this weird feeling that it would be somehow easier than it was. Not easy. But easier.

You don’t want to have the exhaustion and anxiety of trying to find a new voice, but it’s just part and parcel of it sometimes. And I realized I took the job so that would happen, and it comes with some rough road at first. I took the job to be challenged. I was getting a little bit on autopilot with the old show. And that’s certainly not the case now.

It sometimes felt like you were so intent on creating this new thing, this new identity, that you drifted from things that genuinely interested you.

We purposely threw out the baby with the bathwater. And we didn’t realize it until a year in. So we re-indulged our appetites, if you know what I mean. It’s not so much “groove back” as giving ourselves permission to do what we like. [Pauses.] We stepped away from politics to a fault. How about that?

The way to stay hopeful is to acknowledge and to not accept what is absolutely amoral, mentally ill behavior as normal.

— Stephen Colbert

Why do you think it took awhile for you to realize that?

I was trying to do everything — to a fault. I remember on the anniversary of doing the show for a year, I was shaving, looking in the mirror and, as I was wiping the last of the shaving cream off, I went, “God, this is a hard year.” Then I thought immediately, “I wouldn’t have traded it for anything.” Because how would I have learned a new skill? How would I have learned to be able to do a monologue? How would I have changed my voice at all if it hadn’t been for the challenge of this year?

When you did that Showtime election night special, you ended with a moving monologue saying that we “drank too much of the poison” and that we should focus on what we have in common as Americans …

Right. But every time I think that, I also have to remind myself how short I fall of what I hoped for when I said that. That poison cup, man. It’s very hard not to drink from. It’s very tasty.

How do you negotiate the tone of your political commentary without chugging from that cup?

Imperfectly. The way I’ve tried to explain it — both internally and to other people in the business, not the press — is that, at our best, we don’t engage in burning things to the ground. We point to things that are on fire and say, “Do you think that should be on fire? I think that we can all agree it’s on fire, OK? Now, is that something we really want to burn to the ground?”

And the problem with tone is: How close can I get to the fire without being in it? Cynicism is an enormous problem. I’m actually a hopeful person. But the way to stay hopeful is to acknowledge and to not accept what is absolutely amoral, mentally ill behavior as normal.

Trump’s speech at the Boy Scout Jamboree comes to mind. You’re the father of an Eagle Scout. That had to make you angry.

To get children to boo and hoot. “Better a millstone be tied around your neck and you be tossed in the deepest part of the river than you should scandalize one of these.” There’s a moral heresy involved with the president getting children to engage in his own behavior.

Tricky to dance next to the fire with that kind of thing …

I’m not here to scold … and, again, imperfectly, because you can’t help but engage in that. The times you see me being my harshest or scolding, I promise you, that’s not what we wrote. I just get swept up in the emotion of the moment while I’m talking about it.

I’d imagine that it’s hard sometimes not to be swept up …

It’s hard but that’s part of the job, to maintain the discipline of pointing and not finger-wagging. Don’t think you’re changing the world through mime, as I like to say. You’re here as a release valve for people’s emotions. And that’s a very valuable thing.

People would say, “Oh, you say you just do jokes.” I don’t just do jokes. I do jokes. Jokes are important. They saved my life when I was younger. Hopefully we’re making things nicer at the end of the day for people. That’s the entire goal, and that’s the touchstone and the North Star for the tone.

Would the Putin-Trump [vulgar reference to oral sex] joke you made be an example of getting too close to the fire?

I’m not familiar. I’m not familiar. You say you’ve got a “sock holder”? I think I see the lawyers about to come in the room. Yes. That would be an example of perhaps letting my emotions get the best of me. Yes, I would say that would be in the fire, not dancing next to it.

Do you remember a story you once told about a letter J.R.R. Tolkien wrote to a priest who was upset with Tolkien for treating death not as a punishment for the sin of the fall, but as a gift. And Tolkien wrote back: What punishments of God are not gifts? Maybe that’s a way to look at these times of ours.

(Laughs) I hadn’t thought about it that way. That quote’s a good guide for everything. That response — aren’t all punishments God’s gifts? — is such a bigger thought, bigger than a political thought. That’s a personal thought. And the personal is bigger than the political because the personal is almost unfathomable.

Now I feel like I’m the one getting the tone wrong with that question …

(Laughs) I do it all the time myself.

But we’re hitting on the ideal here — the unfathomable in every person — recognizing that and treating people with understanding and empathy …

But you absolutely can’t do it! It’s a goal, but you absolutely can’t do it. I don’t think I’ve ever said this in an interview, but when I was younger, my parents used to quote this French philosopher, Léon Bloy, who said that the only sadness is not to be a saint.

And I always think about that. That’s the great sadness, not to be perfect, meaning not to be a saint, not to see the world the way God does. Which is that everyone is going through a battle you know nothing about. But of course not, because I’m sitting here making absolutely joyful fun of the Mooch [former White House communications director

But you’re not talking about a person. You’re talking about ideas. Donald Trump, yes, he’s somebody’s little boy. But he is his ideas because his ideas are what’s going to affect us. As a man, he can do very little. But his ideas could [pauses for drama] kill us all.

Sounds like you’re just buying into the script of the Fake News Media.

Fake news and fake media … the interesting thing about that is that it’s a heresy against reality. Again, as a Catholic, I was taught that the greatest sin was heresy. Because not only are you a sinner, you are proselytizing and inviting other people into your sinful state through your heresy. You’re a recruiter for your own fallen state.

So Trump is a heretic against reality. Basically, he’s lying for sport. He’s inviting people into his heresy that there is no objective reality.

Your grasp of theology is impressive, sir.

I still carry a pocket Gideon around with me wherever I go.

Wasn’t that a turning point in your life, meeting a Gideon on the street when you were a young man?

Yes, I picked up a box of little pocket Gideons — New Testament, Proverbs and Psalms — from a Gideon on the street in Chicago. It was one of those 20-below days and it was so cold, I had to snap [the New Testament] over my knee to get the pages to turn.

And I immediately opened it to Matthew 5 and it was the Sermon on the Mount. “Do not worry, for whom among you by worrying can change a hair on his head or add a cubit to the span of his life?”

Really, that moment changed my life. I understood what “it spoke to me” meant because it didn’t feel like I was reading it. I just felt like it was literally just talking.

You must feel a debt of gratitude toward that guy from that cold Chicago morning.

That impulse toward gratitude is what originally relinked me to the idea of God.

What are you grateful for these days?

Well, it's always the same thing — which is to exist. That’s the baseline. There’s a great line from this Neutral Milk Hotel song … [bangs on his desk] ... I think it’s “In the Aeroplane Over the Sea.” It goes:

And when we meet on a cloud

I’ll be laughing out loud

I’ll be laughing with everyone I see

Can’t believe how strange it is to be anything at all

So why is there something instead of nothing? Why am I here instead of nowhere? That’s the first thing I have to be aware of. And then I’m grateful for my children and my wife. That’s first and then as the hymn goes, “For the beauty of the earth” comes after that.

ALSO

Anthony Scaramucci tells Stephen Colbert: 'I thought I’d last longer than a carton of milk'

'Art of the Deal' writer predicts that Trump will resign by the end of the year

Seth Meyers calls Trump 'a lying racist' over his Charlottesville news conference

With racial clashes rattling the country, the 'Hamilton' message of inclusion marches on

Sign up for The Envelope

Get exclusive awards season news, in-depth interviews and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.