Cinematographer Haskell Wexler, cancer-ridden and 93, made films until his final days

- Share via

Five days before he died late last year at age 93, two-time Academy Award-winning cinematographer Haskell Wexler delivered a final cut of a documentary that he and a small crew had shot and edited in Los Angeles.

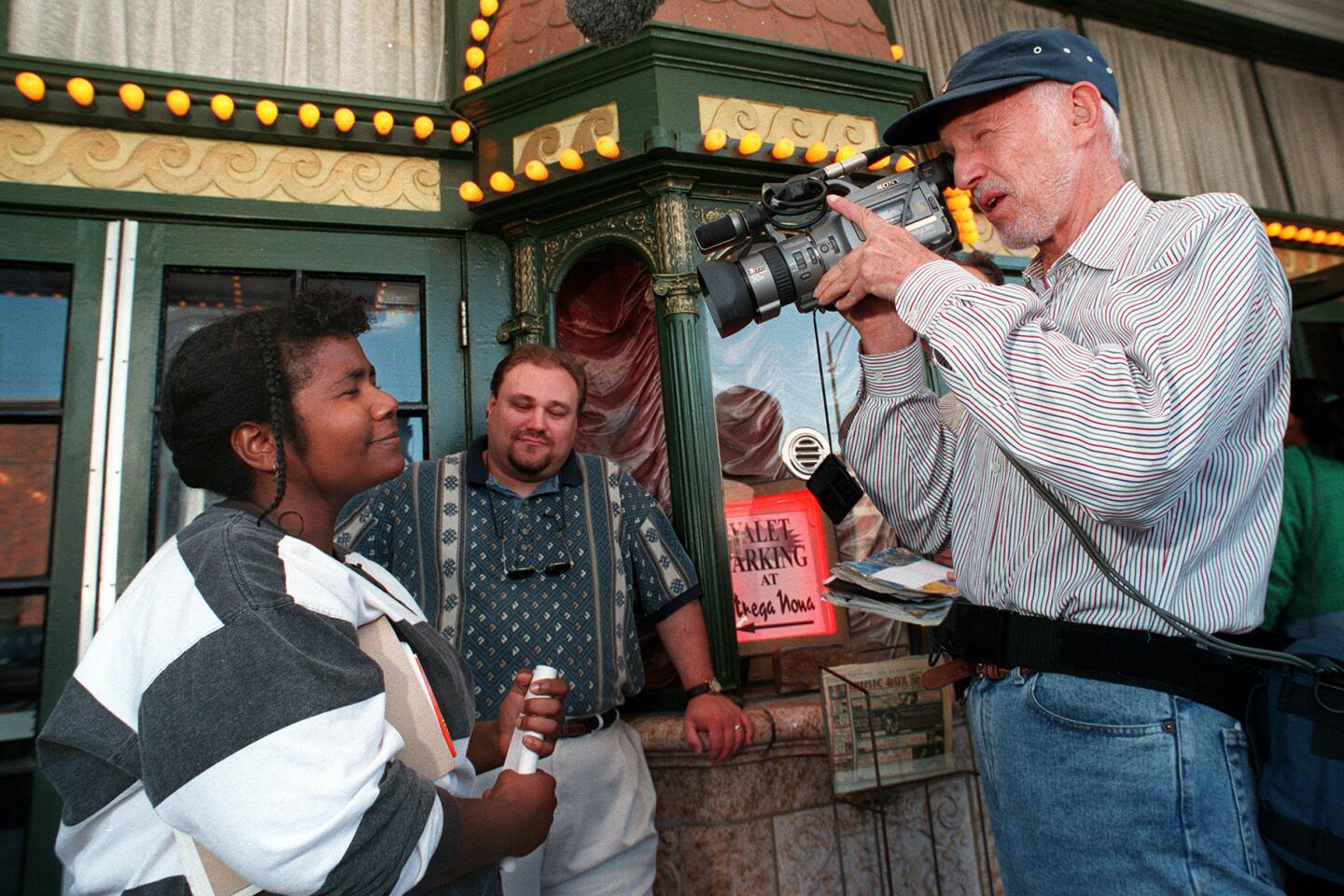

The film, not yet screened for the public, follows young students, many from poor neighborhoods, as they come together at a summer camp devoted to opera to learn the basics of the rarefied art form. Wexler often operated the camera himself, interviewing the kids on the fly as they rehearsed and later performed a civil-rights-themed production of their own.

Wexler heard about the camp through an assistant who was interning at Los Angeles Opera. He agreed to make the documentary for free, with the plan to shoot just a few days. He ended up staying the duration of the two-week camp, shooting hours of footage of 60 students ages 9 to 17.

“He made them feel like they were the important story,” said Stacy Brightman, who heads L.A. Opera’s education and community outreach initiatives.

Wexler submitted the documentary to L.A. Opera on Dec. 22 and died the following Sunday in Santa Monica. L.A. Opera said it will make the documentary, which runs close to 70 minutes, available to camp students and is exploring possible distribution channels.

But don’t call it Wexler’s last movie: The project was one of at least three socially conscious documentaries that he was juggling in his final days.

Widely regarded as one of the most influential cinematographers in Hollywood history, Wexler was a key figure of the New Hollywood era, collaborating with directors such as Hal Ashby, Norman Jewison, Terrence Malick and Mike Nichols. But in his later years, he devoted himself largely to directing politically left-leaning documentaries that he made on tiny budgets.

Those who worked with him say that even in old age, Wexler’s activism remained strong and sometimes confrontational and that the posthumous documentaries exemplify his commitment to social causes.

“He was the kind of guy where if he was shooting the Occupy movement and there was a bag lady or homeless person on the sidewalk, he would go and talk to that person,” said Paul Ferrazzi, a camera operator and frequent collaborator.

Physically, Wexler showed signs of weakness from the treatment he was undergoing in his final months for an unspecified form of cancer.

But “once he got his camera, his age was irrelevant. He had such a passion for making movies,” said actor-writer Ian Ruskin, whose play about founding father Thomas Paine was shot last year by Wexler.

The filmed stage production, captured at the small Lillian Theatre in Hollywood, was intended to debut last year, but “Haskell said we have to wait till next year, for the election,” Ruskin said.

Wexler shot the one-man play with a small crew and later interviewed audience members as they exited. Years ago, he shot the actor’s play about union activist Harry Bridges.

“I think Haskell felt their words and stories needed to be heard.... He saw that as part of his work as a director and cinematographer,” said Ruskin, who is aiming for the Thomas Paine play to air on PBS stations this year.

For Wexler, “his mantra was the smaller, the better,” said Kevin McKiernan, a journalist who worked with the cinematographer on a documentary about Wounded Knee that is in postproduction. “He always believed that smaller is bigger — that history can hitchhike on the eyewitness of little people rather than going to the top and getting official opinions.”

Wexler started working on the project in 2011, traveling to South Dakota to shoot scenes that would explore the aftereffects of the 1973 standoff at the Indian reservation. McKiernan, who reported on the incident more than 40 years ago, said the cinematographer pushed him to turn the project into a first-person account.

“He was never one to be just a cameraman. He was a full participant, whether you liked it or not,” McKiernan said.

Wexler could sometimes upset people with his outspoken ways.

“If he was on a film, and he didn’t like the way things were going, he would talk about it,” said Alan Barker, a filmmaker and frequent collaborator. “If he thought it was serious enough and felt the higher-ups should know, he would.”

Wexler clashed with members of the International Cinematographers Guild over elections. He also rubbed some people the wrong way with his 2006 documentary “Who Needs Sleep?” which chronicled the effects of long working hours and sleep deprivation in the motion picture industry.

Even at the height of his career, Wexler found ways to make politically themed documentaries in between major studio assignments.

He followed Jane Fonda and Tom Hayden to Vietnam in 1974 to chronicle the effects of the war — a film that some detractors criticized as thinly veiled communist propaganda. A couple of years later, he co-directed a documentary on the radical terrorist group Weather Underground, a project he later claimed led to his dismissal from “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

“It was hard for him to work on a movie that was not about much at all or was about stuff that he disagreed with,” said director John Sayles, who collaborated with Wexler on four movies over two decades.

In a scene in Sayles’ labor-themed “Matewan,” Italian laborers sings a Socialist workers song.

“Haskell said he was probably the only cinematographer in Hollywood who knew what those words meant,” Sayles said.

More recently, Wexler made documentaries on the Occupy movement in Chicago and the Bus Riders Union in L.A. He also created short documentaries that he shot guerrilla style and posted online.

“Haskell was constantly shooting — family events, union meetings — sometimes covertly,” said Joan Churchill, the documentary filmmaker and another close associate. “He was so vital, you just didn’t think about him dying. We thought he would live to be 100.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.