Music rolls on at Folsom Prison 50 years after Johnny Cash made history

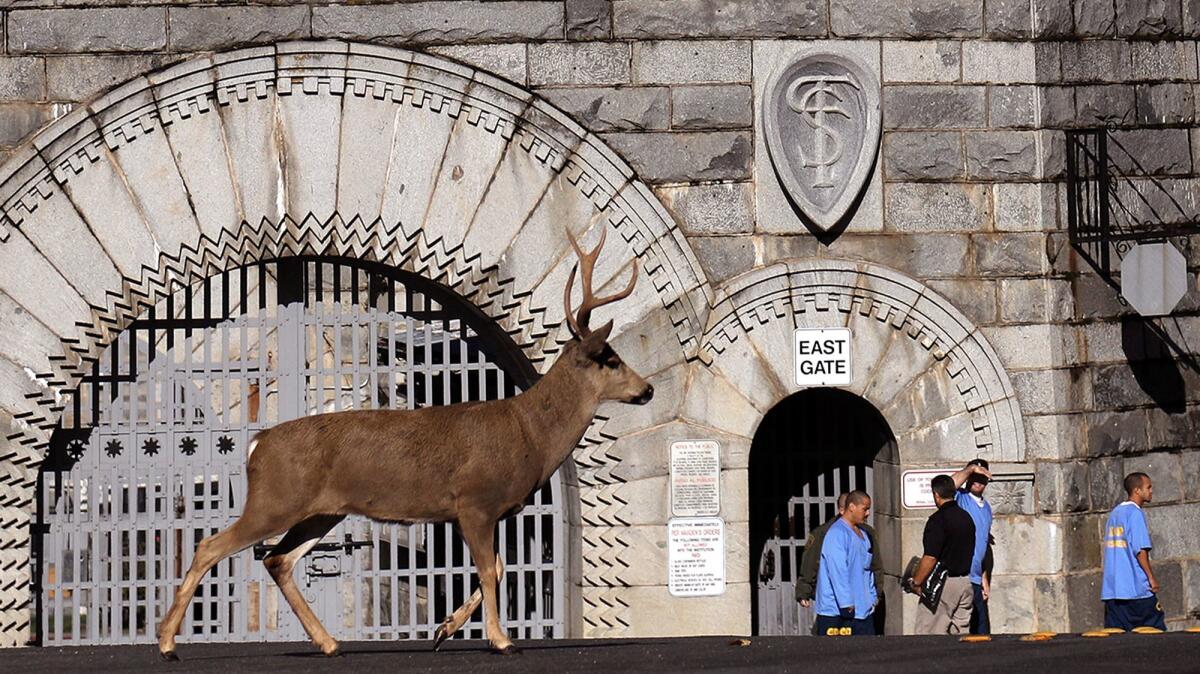

The 50th anniversary of Johnny Cash’s historic live album recorded at Folsom Prison afforded a new look inside the gates of the institution, and at the men who serve time there. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

- Share via

Reporting from FOLSOM STATE PRISON, Calif. — Irony isn’t something the residents of Folsom State Prison spend much time contemplating. But it’s not lost on Roy McNeese Jr. exactly where he spends every Tuesday. That’s when he leads music theory classes for fellow inmates looking to turn their lives around.

McNeese’s classroom is a compact space adjacent to Folsom’s expansive, echo-heavy dining hall. Prisoners wishing to hone their instrumental or vocal chops while serving time, or to learn from McNeese how to write music and better understand songwriting techniques, enter the room each week through a heavily fortified metal door — a door with two words on it:

For the record:

3:00 p.m. Dec. 26, 2017A previous version of this story stated that Johnny Cash’s musical variety show aired on CBS. It aired on ABC.

“Condemned Row.”

Nowadays, however, stark gray cells that long ago housed Death Row inmates — before San Quentin took over housing them in 1937 — are used to store electronic keyboards, drum kits, guitar amplifiers and other gear for the prison’s music program, one of several rehabilitation programs Folsom offers.

The equipment is used by about 40 inmates who play in one or more bands at Folsom, which gained worldwide fame thanks to Johnny Cash’s career-defining 1956 hit “Folsom Prison Blues.” Cash’s song featured a chilling confession that’s central to the song’s stark portrait of life in prison: “I shot a man in Reno, just to watch him die.”

Today, although the prison gift shop doesn’t shy from its connection to Cash — selling “Folsom Prison” and “I Walk the Line” baseball caps, key chains and other tchotchkes — prison officials focus more on a revitalized music program, which they hope will help foster a sense of harmony among inmates.

“When we’re playing, and everybody locks in together, I’m not in prison anymore,” said McNeese, 55. Except he is, and many of Folsom’s artists have quite the rap sheet. McNeese is serving a sentence of 33 years to life with possibility of parole on convictions for one count of second-degree murder and one count of attempted second-degree murder.

McNeese was speaking during a loose band rehearsal in the same dining hall where Cash and his wife, singer June Carter Cash, and their musical entourage performed on Jan. 13, 1968, a session recorded and subsequently released as “Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison.” The album shot to No. 1 on the country charts and helped revitalize his career, which was at a low point at the time largely because of his spiraling substance abuse.

On this day, the feeling of musical connection and emotional release is palpable as three other inmates, with McNeese looking on, power through a hard-driving progressive jazz-rock tune they’ve been working on in his songwriting class.

The transformation of Folsom’s “Condemned Row” into a rehearsal space by all accounts would have greatly pleased Cash, who throughout his life expressed great empathy for underdogs of all stripes, prisoners included.

“I would rather play Folsom for free,” Cash told a reporter for the Folsom Observer in 1967, “than most any other place I know of.”

Cash, in fact, had set his career in motion in 1956 with “Folsom Prison Blues,” which reached No. 4 nationally on Memphis, Tenn.’s tiny, independent Sun Records label. Shortly after, he scored his first No. 1 with the similarly thematically dark “I Walk the Line.”

He played his first performance for incarcerated men in 1957 at Huntsville State Prison in Texas, then did another at California’s San Quentin State Prison in 1958. Famously, one of the inmates present for Cash’s show that day, who often credited Cash’s performance for turning around his life as a trouble-bound young adult, was a young Merle Haggard.

Cash’s bond with society’s outcasts and outlaws came to the fore a decade later when Cash decided to record a live album during a return visit to Folsom, where he’d performed a year earlier.

“Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison” spent four weeks at No. 1 on Billboard’s country albums chart and was named album of the year by the Country Music Assn.

“I don’t think that he knew it would be as successful as it was,” Cash’s daughter, musician Rosanne Cash, said years later, “but I think he knew it was important to do.”

Garth Brooks, country music’s biggest star of the last 30 years, said in a separate interview, “That [‘Folsom Prison’] record is historical, but it’s still timely today. … Let’s say you walk out on stage and that stage is made up of five founding things in country music: Johnny Cash is one of those five founding things.”

In relatively short order, Cash was no longer the performer many had written off as a drugged-out has-been. He was well on his way to rebirth as the iconic Man in Black, revered voice of the downtrodden.

All the renewed interest in Cash paved the way for ABC to tap him as the host of his own musical variety show, a groundbreaking affair that ran from 1969-71. He introduced an revelatory new song, “The Man in Black,” during the show’s second season. Sample lyric:

I wear the black for the poor and the beaten down

Livin’ in the hopeless hungry side of town

I wear the black for the prisoner who has long paid for his crime

But is there because he’s a victim of the times

The historic nature of the “At Folsom Prison” album and interest in next month’s 50th anniversary prompted prison officials to allow about a dozen reporters to tour the facility. It was a significantly larger media contingent than accompanied Cash half a century earlier.

Yet Folsom Prison staff members express mixed feelings about the Cash connection.

“Did Johnny Cash make Folsom Prison?” asks Jim Brown, who has worked at Folsom for 47 years: 32 as a guard, the last 15 as a volunteer in the modest prison museum that sits a couple of dozen yards across a paved access road from the famous stone East Gate, where Cash posed for photos shot by rock photographer Jim Marshall.

“The staff here makes Folsom,” Brown said.

In any event, changes over time render Cash’s imprint less impactful than it was during his many visits to Folsom.

Photos from 1968 show a prison population that was largely Anglo, with a smattering of Latinos among them. Today the inmates, who number about 2,500, are predominantly black, Latino and Asian — hardly a target demographic for vintage country music.

Consequently, the musicians at Folsom have formed hip-hop, hard rock/heavy metal, Latin rock, alt-rock, smooth jazz and progressive rock ensembles within Folsom’s walls.

But zero country bands.

Still, McNeese, a keyboard player who was part of the influential L.A.-area Uncle Jamm’s Army hip-hip collective before he went to prison in 1997, said one edict he enforces on those in the music program is that “there are no cliques — no separation among groups, no racial barriers.”

It’s an idea similar to one expressed by former inmate Millard Dedmon, who was interviewed for the liner notes to the “At Folsom Prison” album.

“It doesn’t matter whether he’s a white boy with a country music band, or a black boy with a blues band,” Dedmen said. “The thing was, he had somebody come in to us. Somebody from the outside.”

“Johnny Cash is one of the legends — he definitely has his own voice,” said inmate Gary Calvin, 59, one of the anchors of the music program who plays bass for several groups, including the trio that was on display for visiting reporters and camera crews.

Cash always expressed his appreciation for the prison crowds who heard him play.

The Folsom concert, Cash said, put him on the road to transformation.

“I knew this was it,” Cash later told biographer Robert Hilburn, the L.A. Times’ longtime pop music critic who also was the only reporter to cover the 1968 Folsom show. “My chance to make up for all the times when I had messed up. I kept hoping my voice wouldn’t give out again. Then I suddenly felt calm. I could see the men looking over at me. There was something in their eyes that made me realize everything was going to be okay. I felt I had something they needed.”

Calvin has been in state prison since 2005 and at Folsom for a little more than five , he said. He hopes to be released “in three or four more years, if things go right,” although state records show he is not eligible for parole until March 2029. He’s serving a life sentence with possibility of parole as a third-strike offender, most recently convicted for assault with a firearm, possession of a firearm by an ex-felon and battery with serious injury.

His musical taste runs more to hip-hop, soul and R&B. He and many of his brethren responded enthusiastically to a performance in August by Chicago rapper, actor and film producer Common, who last year won the Academy Award for the song he wrote with John Legend, “Glory,” for the film “Selma.” He came to Folsom this year on his “Hope and Redemption” tour that visited four prisons in four days.

“Common was really good at connecting with people,” said David Sims, 38, of Sonoma City, looking up from the automobile skeleton he was attempting to repair with Jamey Walker, 42, of Los Angeles, in a former airplane hangar that now serves as the prison’s auto shop training facility.

Not far away, another group of prisoners train to become electricians, while others study to be plumbers or welders.

“We wish there were more performances like that,” Sims said. “It really brought everybody’s morale up for a while. Once we get back out there, if we can participate in society, we can be more positive.”

Common later noted in an interview that “visiting these prisons and speaking with the men and women inside … had a profound impact on me. I believe it is my duty to lend my voice to the voiceless and stand with the men and women in prison who have been silenced for so long. We need a justice system that is a tool for rehabilitation rather than a weapon for punishment.”

Indeed, change — specifically rehabilitation — is what Folsom officials want to highlight rather than the anniversary of Cash’s celebrated concert. In town, however, Folsom’s visitors bureau is working full tilt to develop the Johnny Cash Prison Art Trail into a significant tourist attraction.

So far, the first phase of the projected $8-million endeavor has carved out a 1.4-mile bike trail that emphasizes Cash’s musical legacy in the region. That includes a giant sculpture shaped like a guitar pick and a bridge echoing the design of the guard towers at the nearby prison.

But music programs such as the one McNeese and a few dozen others now take part in, after flowering in the ’70s and ’80s, withered in the early 2000s because of budget cuts and prison overcrowding. A revival began in 2013, and in 2017 rehabilitative programs returned to all 35 state prisons, according to Krissi Khokhobasvhili, public information officer for California Dept. of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

The value of such programs was studied by the Rand Corporation, a nonprofit research organization. In a 2013 report, Rand researchers concluded that “a $1 investment in prison education [reduces] incarceration costs by $4 to $5 during the first three years post-release.”

The upshot, the report said, is that “Prison inmates who receive general education and vocational training are significantly less likely to return to prison after release and are more likely to find employment than peers who do not receive such opportunities.”

In bassist Gary Calvin’s mind, he hopes to use his experience at Folsom to his advantage.

“I’d like to be someone who is able to make a positive difference,” Calvin said, and that’s part of his motivation for working with other prisoners in the music program. “You take a wrong turn here, a wrong turn there — it happens. But it’s not over. Things can change.”

Follow @RandyLewis2 on Twitter.com

For Classic Rock coverage, join us on Facebook

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.