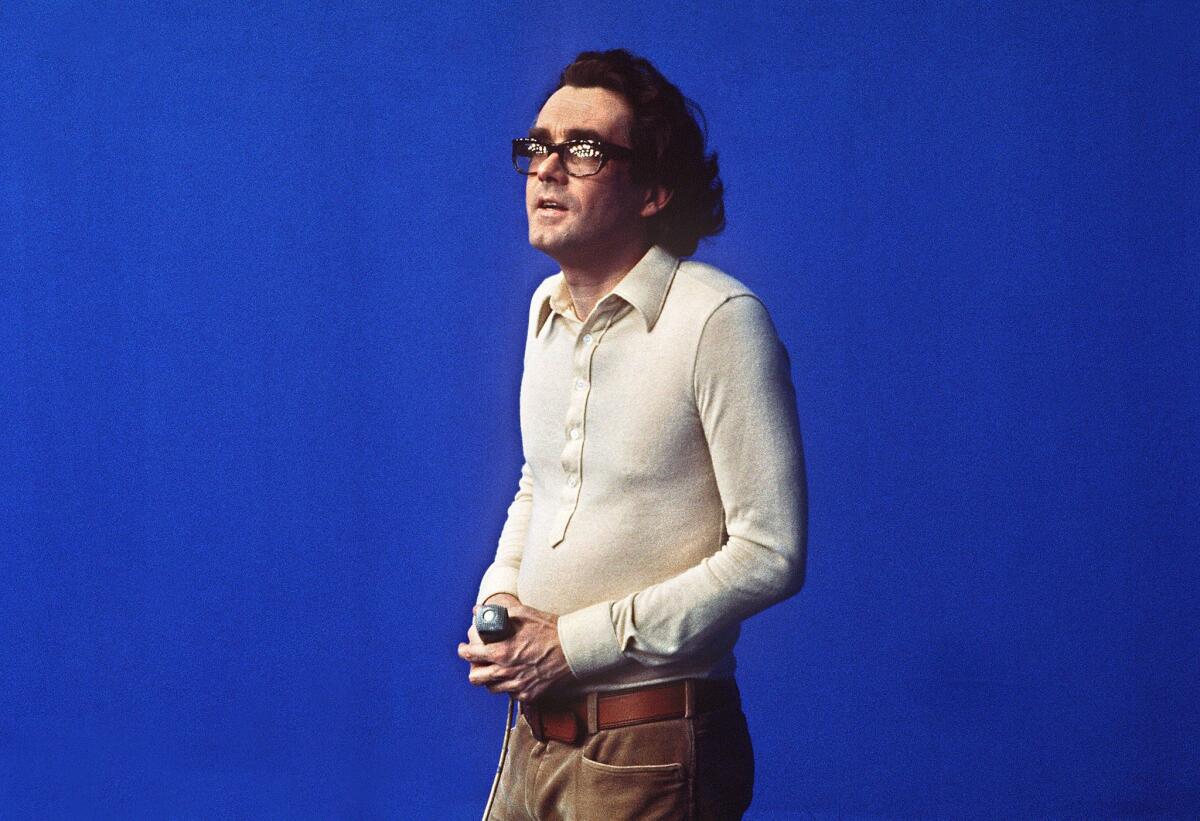

Remembering Michel Legrand, whose love songs always told a story

- Share via

Michel Legrand loved a good love song.

For this French composer and pianist, who died Saturday in Paris at age 86, romance was an inexhaustible subject in the lush and sentimental music he wrote for movies and for the pop stars who turned many of his songs into standards.

And by romance, I don’t mean mere flirtation or infatuation; I mean l’amour of the full-on heaving-chest variety. With his enveloping arrangements and his dramatic melodies — sung over the decades by the likes of Barbra Streisand, Tony Bennett, Aretha Franklin, Johnny Mathis and Frank Sinatra — Legrand summoned the feeling of being swept away by love.

Is it any wonder that his best-known tune was “The Windmills of Your Mind”?

In a career that stretched over more than half a century, Legrand composed hundreds of film scores (for movies as varied as “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg,” “Yentl” and the James Bond picture “Never Say Never Again”) and made albums with Sarah Vaughan and Lena Horne, among others.

And though the words of his songs typically weren’t his creation — he worked for years with lyricists Alan and Marilyn Bergman — his passionate music could inspire flights of fancy like that in “The Windmills of Your Mind,” with its indelible image of a “carousel that’s turning running rings around the moon.” (“Windmills,” featured in 1968’s “The Thomas Crown Affair,” earned Legrand and the Bergmans an Academy Award for original song, the first of three Oscars the composer won.)

He could similarly push filmmakers to emotional extremes, as in “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg,” Jacques Demy’s swooning movie musical from 1964 about a pair of gorgeous young lovers separated by war.

In one knowing scene from that film, Geneviéve (played by Catherine Deneuve) tells her mother that she’ll die as a result of a broken heart, to which the mother replies that people die from love only in the movies — a cinematic tradition the pop-operatic Legrand was proud to bolster.

Singers too responded to the depth of feeling in his music, which he began writing after establishing himself first as an arranger and piano player.

Listen to any three of the dozens of recorded interpretations of “Windmills,” for instance, and you’ll hear three different ways of thinking about the song’s yearning regret (just as Legrand had earlier offered his own spin on familiar material by Cole Porter and Dizzy Gillespie).

For Dusty Springfield, the tune was a lament for the road not taken, while José Feliciano found a kind of ecstasy in its gentle harmonic climb. And Streisand? She did “Windmills” as a ghost story, more or less — haunting and beautiful in equal measure.

Other songs by Legrand proved equally adaptable, in part because their preoccupation with such a fundamental theme — love will both save and destroy the lover — ensured they’d survive whatever shifts in style they met.

Take “How Do You Keep the Music Playing?,” introduced by James Ingram and Patti Austin in 1982’s “Best Friends” as a quiet-storm R&B number fully of its era. Yet just a few years later, Bennett made an orchestral ballad out of the tune, followed by Mathis’ stripped-down voice-and-piano take and later a sleek pop rendition by Celine Dion.

Maybe Adele will get around to singing it one day; her voice is certainly well suited to the sort of sweeping melodic lines Legrand also devised for “The Summer Knows” and “I Will Wait for You” and the Grammy-winning “What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life?”

Then again, the vision of romance presented in these songs isn’t one we see much in pop anymore; nowadays, the notion of surrendering to love feels … problematic, let’s say.

But not in Legrand’s music, which you happily allowed to take you up even as you knew you were bound to come back down.

Twitter: @mikaelwood

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.