‘Man in the Middle’ separates Ruben Salazar from his myth

- Share via

His is a name that has appeared in this publication’s pages hundreds of times — as an author and as a subject. It’s a name that calls up notions of the Latino struggle for civil rights and the radical Chicano movement in Los Angeles.

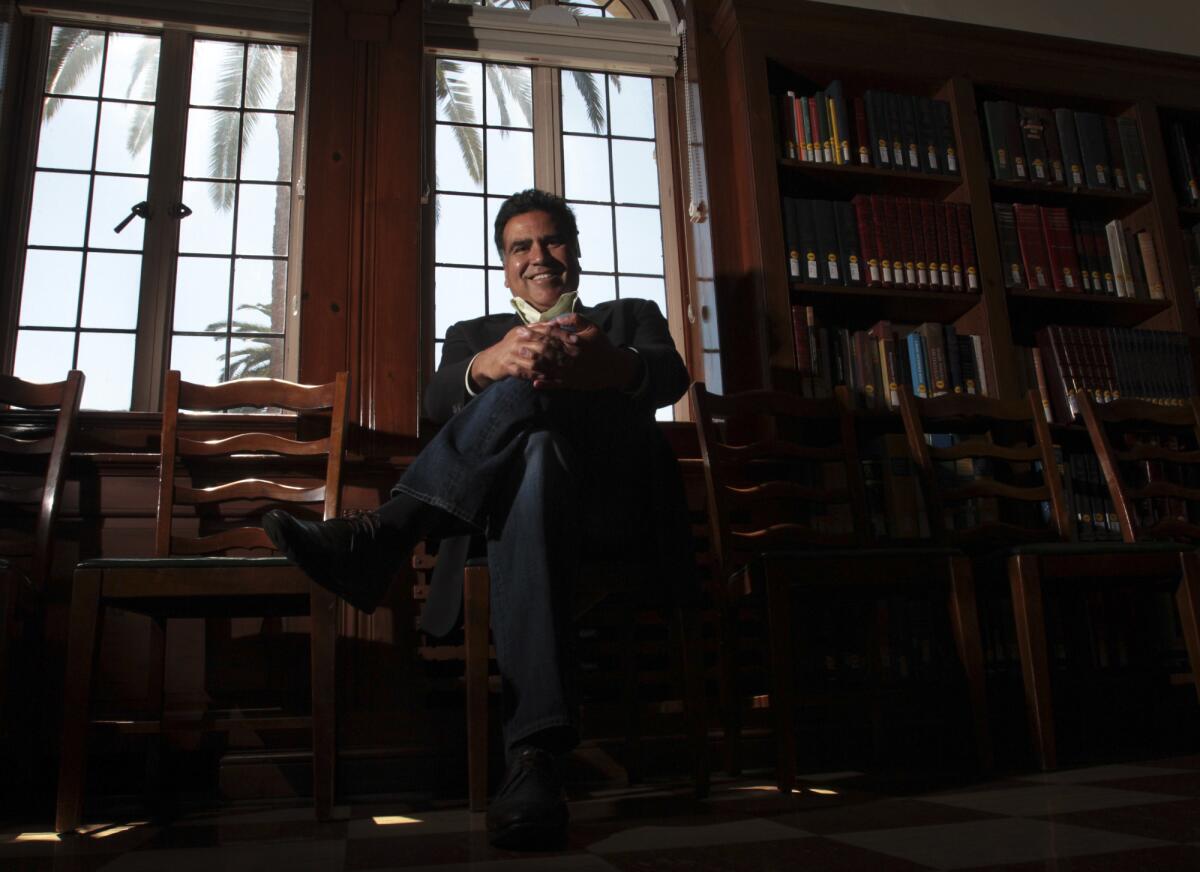

It’s also a name that initially made filmmaker Phillip Rodriguez groan when someone suggested the life behind the name as a subject for his next documentary.

The legacy of former Los Angeles Times reporter and columnist Ruben Salazar has reached folklore heights since the journalist’s suspicious death in 1970 at age 42. And therein lies Rodriguez’s point of contention.

“What I knew about the Salazar story was so completely uninteresting and sort of beat up,” says the 54-year-old director, who was too young at the time of Salazar’s pioneering work to know the man now shrouded in symbolism.

“It was just kind of Chicano mythos — this very flat image of Ruben as a martyr,” Salazar continues. “But this was a man who was living and real. He wasn’t an activist or a politician. He was a journalist doing his job. For me, it became about presenting something historical, not religious.”

DOCUMENTS AND ARCHIVES: Read more from The Times about Salazar and the investigation into his death.

And so Rodriguez made “Ruben Salazar: Man in the Middle,” a documentary airing Tuesday on PBS, with the aim of dimensionalizing the newsman.

The film debuts at an interesting time — coming on the heels of the recent theatrical release of a Cesar Chavez biopic, which drew some criticism for painting a portrait of the labor leader in hushed tones and reverence.

“My father was all about the facts,” says Stephanie Salazar Cook, Ruben’s daughter. “He’d be the first one trying to tear down the myth that surrounds his name. And so I hope people discover there’s a man more interesting than his fame.”

As one of the most prominent Latino journalists of his time, Salazar has been immortalized across Los Angeles and Southern California for his work documenting the era of Brown Berets and Vietnam protests. Murals have showcased his image. Exhibits have displayed his work. Parks and schools bear his name. Just last week it was Ruben Salazar Day in Los Angeles. He’s also part of a select group of figures to be commemorated on a U.S. postage stamp.

But Salazar’s prominence is rooted in the journalist’s own recounting of the plight of being Latino in America. This is why Rodriguez made Salazar’s words a key component in separating the man from the myth. Cook gave Rodriguez access to Salazar’s personal journal, and those private writings are woven throughout the documentary, highlighting his internal battles with identity, his work and the world around him.

Born in the Mexican border town of Juárez but raised across the river in El Paso, Texas, Salazar grappled with the tension of cultural assimilation.

“The international bridge that connected Juarez and El Paso symbolized the division of my life,” Salazar writes in a journal passage featured in the film. “No matter which way I crossed, I could not leave the other side behind.”

ON LOCATION: Where the cameras roll

Salazar began his work at The Times in 1959. For a time he held a coveted foreign correspondent spot, eventually becoming bureau chief in Mexico City. He was brought back to L.A. to cover the rising Chicano movement. But Salazar, wary of being pigeonholed, was vocal to his bosses about not wanting to cover the subject, as the film details.

“He didn’t want to be viewed as ‘The Mexican Guy,’ ” Rodriguez says. “He was middle-class. He was cosmopolitan. He lived in Orange County. He was almost like a Don Draper. Which is all weird because it doesn’t conform to the Chicano narrative.”

Yet it was his work documenting Latino struggles — from 1968 until his 1970 death — at The Times and later as news director for radio station KMEX that would raise his profile. And it was while covering a Chicano antiwar protest in East Los Angeles that Salazar met his death. He was sitting at a bar, taking refuge after rioting broke out, when a tear-gas canister was fired inside by a sheriff’s deputy, hitting Salazar and killing him.

The debate over whether his death was accidental or part of a police conspiracy has endured. And a noteworthy inclusion in the film are the long-confidential L.A. Sheriff’s Department files — autopsy photos, investigative details — on Salazar’s death obtained after a fraught battle for their release with former Sheriff Lee Baca.

“Getting those files was the most challenging thing I’ve ever experienced,” Rodriguez says. “But we needed them. We had to excavate the facts to go beyond the piety. All the sexy stuff — the story of Ruben’s death — that information was entirely unavailable.”

“Man in the Middle” also comes equipped with documentary staples, interviews from friends, family and former colleagues eager to keep Salazar’s story going. Also incorporated throughout the film are memorabilia and writings dating back to his birth in Mexico. The personal archives, including the police files, are housed at the USC Libraries.

“The lesson it taught me is you never know when history is going to be made because it looks like the day-to-day,” says Bill Drummond, a former Times reporter who was working the Saturday shift when the call came in about Salazar’s death. “It’s perfectly understandable that it would be examined and re-examined. And it will continue to be re-examined. The position of Latinos in California that was only hinted at in the ‘70s is now a profound reality. That’s why we have to remember the past.”

-------------------------------------

‘Ruben Salazar: Man in the Middle — A Voces Special Presentation’

Where: KOCE

When: 9 p.m. Tuesday

Rating: TV-PG (may be unsuitable for young children)

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.