How a beachfront gas plant explains California’s energy problems

- Share via

This is the April 1, 2021, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

When the California Public Utilities Commission recommended 17 months ago that a gas-fired power plant on the Redondo Beach waterfront remain open beyond 2020 — over the objections of local officials and clean energy activists — Commissioner Martha Guzman Aceves made a commitment to the city’s mayor.

“I pledge to you, Mayor Brand, that I will never support a further extension,” she said.

Now it looks like that promise will be put to the test.

The State Water Resources Control Board is again being asked to extend the gas plant’s operating life, this time past the end of this year. Officials say the climate-polluting facility may be needed in summer 2022 — especially if there’s another punishing heat wave like the one that resulted in brief rolling blackouts last August.

The fight over Redondo Beach Generating Station is a fascinating microcosm of the clean energy challenges confronting California and the nation. So let’s take a step back and look at how we got here.

Our oceans. Our public lands. Our future.

Get Boiling Point, our new newsletter exploring climate change and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The story begins in 2010, when the state water board voted to phase out the use of ocean water for cooling machinery at 19 power plants along the coast. As The Times reported back then, intake pipes at those facilities “suck in enough seawater to fill Lake Arrowhead, then spit it out again, a little warmer and a lot deader,” killing fish that can get trapped against intake screens and larvae that are small enough to make it through the screens.

The owners of most of the power plants have since complied, either by shutting down the offending generators, replacing them with fancy new units that don’t use ocean water for cooling, or otherwise dramatically reducing harm to marine life.

Redondo Beach Generating Station was one of several gas plants that was supposed to ditch so-called “once through cooling” by Dec. 31, 2020. Plenty of time to install fish-friendly technology or figure out how to replace all that energy generation, right?

That’s not how it worked out. The plant’s owner, AES Corp., spent the next decade fighting with local residents who wanted to see the facility replaced with a public park. A coalition that included Bill Brand, who was eventually elected Redondo Beach mayor, defeated several AES redevelopment plans, as well as an effort to rebuild the gas plant with air-cooling technology.

Then in 2019, the California Public Utilities Commission and the California Independent System Operator began warning that the state could face power shortfalls in summer 2021. They asked the state water board to please extend the shutdown deadline for Redondo Beach and three other Southern California gas plants.

Disaster struck sooner than expected. Or if not disaster, then at least hardship. The state suffered its hottest August on record last year, with Death Valley hitting 130 degrees Fahrenheit during a midmonth heat wave. The entire American West baked, limiting California’s ability to import electricity from its neighbors. The Independent System Operator ordered blackouts on two consecutive evenings, putting as many as half a million homes and businesses out of power for as long as 2½ hours.

To no one’s surprise, two weeks later the state water board voted to let the four Southern California gas plants stay open past Dec. 31, 2020. Three of the four were given three-year extensions; Redondo Beach’s reprieve was limited to one year, in a concession to Brand and other local officials who opposed any kind of leeway.

That brings us to today. State officials are mostly focused on lining up new energy resources for this summer, but they’re also looking ahead to next year. And last week, the Statewide Advisory Committee on Cooling Water Intake Structures — the acronym is SACCWIS, for those of you keeping score at home — voted to recommend that the Redondo Beach gas plant be given another new lease on life, with the shutdown deadline delayed until the end of 2023.

I called Brand to ask his opinion. He was not happy.

“If the state of California is going to rely on one 70-year-old power plant to secure their energy needs, we’ve got big problems,” he said. “There’s no question this was a failure in planning and a failure in grid management.”

Whether or not the state should have been prepared — I’ll leave that for you to judge — we’re in this situation because of the rapidly changing nature of the power grid.

It used to be that as long as utility companies had enough electricity lined up to serve customers on the hottest summer afternoons, they’d be fine the rest of the year. But solar power has changed the equation. Now it’s the evening hours — when the sun goes down yet temperatures can remain high — that are increasingly dicey. That was the problem period last summer.

Utilities are adding thousands of megawatts of lithium-ion batteries, which are useful for banking solar energy generated during the middle of the day and saving it for the evening. But the batteries revolution is a work in progress. For now, gas plants do the bulk of the work keeping the lights on after sundown. Hence last week’s vote by the SACCWIS.

“One of the toughest parts of this job is we have to make really, really difficult decisions that are painful,” said David Hochschild, chair of the California Energy Commission, when I asked him about Redondo Beach. “We are going down a road where we have to keep that facility open longer than we like. However, it will not be operating much.”

The Energy Commission and other agencies conducted a “stack analysis” of summer 2022 energy supplies, concluding California could once again find itself short of power, specifically in July and September, without Redondo Beach. If the plant were to stay open, they found, the shortfall would mostly vanish.

State officials described the projected shortfall as “conservative,” saying it could actually be worse if utilities don’t get batteries and other new power supplies online as fast as they’re supposed to, or if importing electricity from other western states gets harder — which seems likely, by the way. Yet another coal plant, this one in Montana, closed just yesterday.

At the same time, it’s clear that Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration is being extra cautious after last year’s blackouts, which the governor does not want to repeat, especially with a likely recall vote looming. A Redondo Beach extension is one of many strategies his appointees are pursuing, from building batteries, to paying people to use less electricity, to adding capacity at existing gas plants, to technical market fixes.

“The imperative right now, given the events of last August, is to be absolutely certain we can provide electric reliability,” Hochschild told me. “When you have a threat to reliability like we did last August — even if it’s only four hours over two days — that becomes a very significant event. We cannot have people lose confidence in the reliability of the electric grid.”

And therein lies the challenge of transitioning California’s economy away from fossil fuels, which I described last week as, “Move fast, don’t break things.” Close the Redondo Beach gas plant too quickly, and maybe hundreds of thousands of people find themselves without air conditioning on a hot summer night. Choose not to close it, and you’re only putting off the day when bold steps will be needed to wean the state off fossil gas — and the longer you wait, the more the planet warms.

This one gas plant will not make or break California’s climate goals, or the electric grid. But it’s a useful case study because the choice is so stark. Shut the plant on deadline, or let it keep running. There’s no middle ground.

These types of decisions impact real communities in tangible ways. More than 20,000 people live within a mile of Redondo Beach Generating Station and breathe the nitrogen oxides and fine particulates it emits. Redondo and neighboring Hermosa Beach are actually suing the state water board, arguing the agency failed to properly analyze the environmental impacts of last year’s gas plant extensions, a claim agency officials have rejected.

I also reached out to AES Corp. for comment. I got a written statement from Mark Miller, market business leader for California, who said the company is “committed to support the responsible transition to a carbon-free energy future.” He suggested two more years of operation in Redondo Beach “can help achieve this goal” by reducing the risk of blackouts during extreme heat.

There’s a final twist to this story: It turns out one of the three gas units at Redondo was completely unavailable during both days of rolling outages last August, due to what state officials describe as “plant trouble.” The other two units were generating slightly less electricity than usual — in one case, ironically, because of the extreme heat.

On the power grid, nothing is easy.

Here’s what else is happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

As I write this newsletter on Wednesday, President Biden is announcing a $2.25-trillion American Jobs Plan that would invest heavily in fighting climate change, should Congress approve. Biden called it “a once-in-a-generation investment in America, unlike anything we’ve seen or done since we built the interstate highway system and the space race decades ago,” as Chris Megerian reports for The Times. Here are some of the details:

- More than $170 billion to make America a global leader in clean cars, by installing 500,000 charging stations, electrifying 20% of the nation’s school buses and buying electric post trucks, among other steps (story by Anna M. Phillips, L.A. Times)

- A bigger and more sweeping effort to support clean energy technologies than what President Obama attempted with the 2009 economic stimulus bill, which, as I’ve reported previously, may have been too cautious (Coral Davenport, New York Times)

- Funding to plug abandoned oil and gas wells, reducing methane emissions (Marianne Lavelle, Inside Climate News)

- Clean drinking water for millions of people by replacing every lead water pipe in America (Todd Spangler, Detroit Free Press)

Here’s a full rundown of how the money in Biden’s infrastructure plan would be spent. And lest we forget that building stuff is hard, The Times’ Ralph Vartabedian reports there are even more delays on California’s bullet train. At least Los Angeles County’s buses and trains will be returning to full service thanks to already-approved federal funding, per my colleague Dakota Smith.

In other infrastructure news, Emily Atkin has been doing tremendous reporting on the ground in Minnesota covering resistance to the Line 3 oil pipeline. Here’s her recent HEATED newsletter on Indigenous women being “kenneled, strip searched, shackled and held overnight.” In other installments, Emily wrote about pipeline developer Enbridge plastering local newspapers with ads and helping to fund Minnesota police. She also spoke with Jane Fonda, who is not happy with Biden.

AROUND THE WEST

A gray wolf has journeyed from Oregon further south into California than any other wolf in modern times, all the way to Fresno County. For the odyssey of the beast known as OR-93, here’s my colleague Louis Sahagún, who says conservationists are thrilled to see a new member of this endangered species making itself at home. In other wolf news, Mountain West News Bureau’s Nate Hegyi discovered that Montana Gov. Greg Gianforte killed a wolf near Yellowstone National Park and was cited for violating hunting regulations. (Gianforte is the guy who pleaded guilty to misdemeanor assault after body-slamming a reporter.)

California farmer Mike Abatti is taking his case against the Imperial Irrigation District to the U.S. Supreme Court. I wrote last year about why Abatti’s lawsuit against the irrigation district, which controls the single largest share of Colorado River water, should matter to people across the West. An appeals court ruled against him, so now he’s petitioning SCOTUS to intervene, as Mark Olalde reports for the Desert Sun. (See also my 2018 deep dive into Abatti.)

Speaking of the Supreme Court, Chief Justice John Roberts is openly soliciting challenges to the Antiquities Act. That’s the law presidents have used for more than a century to designate national monuments, including many on public lands in the West. Roberts suggested presidents may be abusing the law by ignoring a requirement that monuments be “limited to the smallest area compatible with the care and management of the objects to be protected,” as Jennifer Yachnin reports for E&E News.

ALONG THE COAST

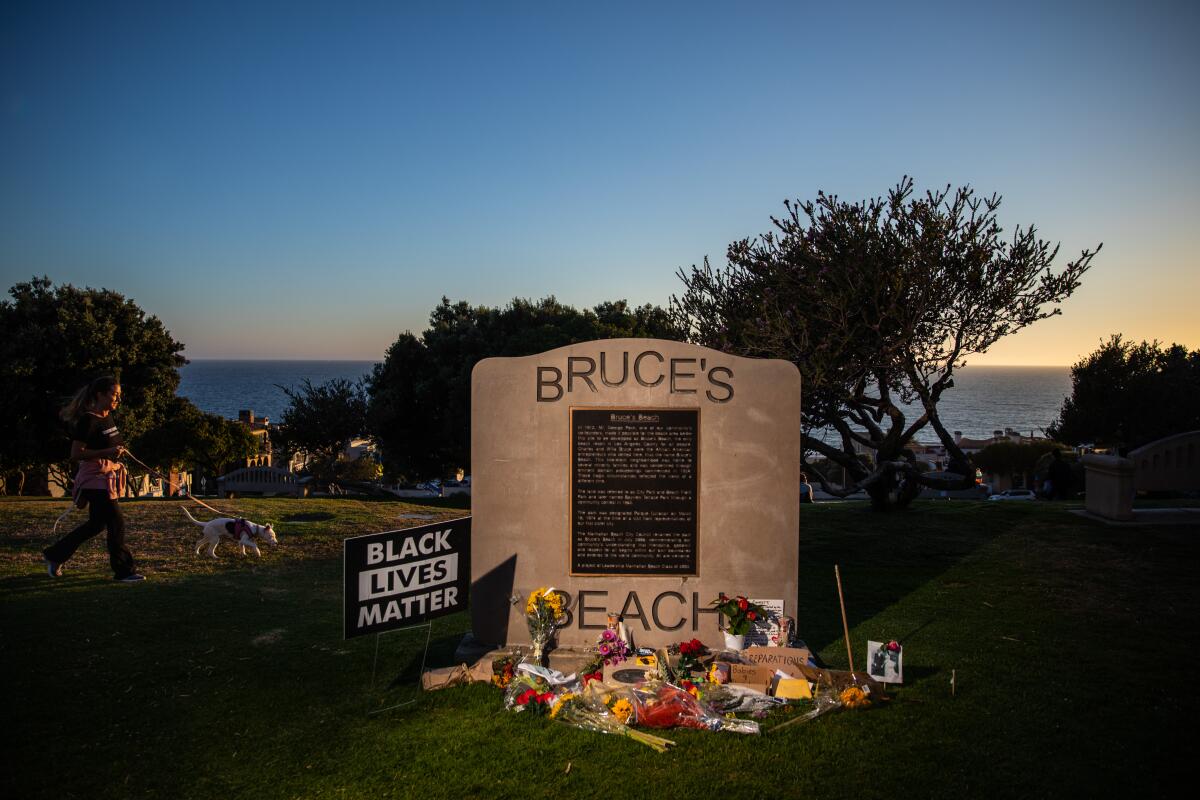

How should Manhattan Beach atone for seizing valuable beachfront property from a Black family a century ago? That’s the question posed in this powerful story by my colleague Rosanna Xia, who’s been writing about making the California coast accessible to everyone, not just the privileged few. See also this fascinating piece by The Times’ Julissa James about Black surfers carving out a space for themselves in Manhattan Beach, where they’ve sometimes faced racist slurs and general hostility.

The California Legislature is considering at least 17 bills dealing with sea level rise. Here’s a rundown from San Diego Union-Tribune columnist Michael Smolens. Proposals include $100 million in annual grants to help coastal communities adapt.

Climate change is doing a lot more damage to the oceans than just making them rise. As Lauren Sommer chronicles for NPR, great white sharks are showing up off parts of the California coast where they shouldn’t be, in a sign of the challenges — but also the conservation opportunities — that the oceans present for the Biden administration. Lauren also wrote about strategies for saving California’s last remaining kelp forests. Apparently we can help by eating purple sea urchins, rather than the red variety.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

New Mexico is suing the Nuclear Regulatory Commission over plans for a nuclear waste storage facility. The state says a license granted to Holtec International could cause “imminent and substantial endangerment” to the Land of Enchantment, as the AP’s Susan Montoya Bryan reports. She also reports that advocates and lawmakers hope to expand a payout program for people exposed to radiation from nuclear tests and uranium mining, which doesn’t cover nearly everyone affected in western states.

Kern County’s board of supervisors is urging Gov. Gavin Newsom to let a tax exemption for large solar farms expire in 2024. They say the exemption — which keeps property taxes for solar plant owners artificially low — has resulted in $103 million in lost revenue for the county, home to lots of renewable energy development, per the Bakersfield Californian’s Sam Morgen.

Why was Marathon Petroleum allowed to expand oil storage at the largest refinery on the West Coast, in L.A.’s Wilmington neighborhood and the city of Carson? In part because the South Coast Air Quality Management District doesn’t consider climate change in permitting decisions for oil companies, according to this investigation by Ingrid Lobet for Capital & Main.

ONE MORE THING

You may have heard that German automaker Volkswagen is changing the name of its U.S. subsidiary to “Voltswagen,” to highlight its focus on electric cars. Turns out that’s false. The company was lying to reporters when it insisted the announcement was real and not a publicity stunt, David Bauder reports for the Associated Press. Not a great look for a company that still hasn’t recovered from its massive diesel scandal.

In electric vehicle-related news that’s more fun and more useful than Volkswagen’s stunt, Maddie Stone — author of the excellent Science of Fiction newsletter — wrote about where humanity might mine lithium in space. Sounds like Mars is our best bet.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.