How does sea level rise challenge modern notions of property lines?

- Share via

This story originally published in Boiling Point, a newsletter about climate change and the environment. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Hello again! It’s Rosanna Xia, coastal reporter for the Los Angeles Times, filling in this week for Sammy Roth.

Hang with me today, we’re about to geek out on an environmental doctrine that dates back to the Byzantine Empire — and how this ancient principle must now be upheld in the face of sea level rise.

Here in California, a landmark law (dubbed the Coastal Act) declared decades ago that the beach is a public treasure that must be shared by all.

Dramatic clashes with developers and wealthy homeowners have become all too familiar, but this zero-tolerance for private beaches and high rises is why the state’s shoreline feels so different from Miami’s.

The Coastal Act is a remarkable commitment to the public trust doctrine, which traces back to Justinian I, who declared in 533 C.E. that “the following things are natural law common to all: the air, running water, the sea, and consequently the seashore.” This notion — that certain lands should be held in trust by the government for the benefit of all people — evolved into English common law, which the United States then adopted and California later wrote into its state constitution.

Which brings us to where we are today: Along the California coast, the public trust is delineated by the mean high tide line. The state, and therefore the public, has rights to most land covered and uncovered by the tide (i.e., the beach), as well as lands that were historically below the tide line but have since been artificially drained or filled (i.e., wetlands).

These lines in the sand were all fine and good when we still had ample sand to go around. But sea level rise has made things a lot more complicated: What happens when the tide line starts to move inland because of climate change? At what point does private property become public property — and how do we draw that line?

Squeezed out, too, between rising seas on one side and human infrastructure on the other, are the vanishing salt marshes that once nurtured many of the world’s most endangered species. Studies have also found that two-thirds of our beaches in Southern California could drown in the coming decades. So when all that we hold dear cannot be saved, what becomes the priority?

To make sense of some of these questions, I called up Kate Huckelbridge, who was recently appointed to lead the California Coastal Commission into its next chapter. An environmental engineer by training and no-nonsense in her ways, Huckelbridge is not one to sit on conflict. She has navigated her fair share of complicated issues, such as offshore oil drilling and power plant permitting, and, for a time, she also served as the agency’s tribal liaison.

What we discussed was admittedly a bit wonky at first: We caught up on the commission’s new “Public Trust Guiding Principles and Action Plan,” and Huckelbridge expressed the need to create a map or inventory of sorts, to pinpoint which beaches will need the most urgent attention as the public trust line runs up against seawalls and other hardened boundaries.

But then our conversation took an interesting philosophical turn. Sea level rise is posing unprecedented challenges, Huckelbridge told me, but it is also an opportunity. It gives us a chance to reassess what we value as Californians, and what principles we want to stand for going into the future.

Rising water is also forcing us, willing or not, to reconsider what it truly means to project Western notions of permanence along a line inherently meant to change each day with the tide.

Here is a snapshot of our conversation, edited for clarity and brevity:

So what can agencies like the Coastal Commission actually do to protect the public commons in the face of sea level rise?

Huckelbridge: The first thing is acknowledging the moving nature of the tide, and we haven’t always done that in the past — oftentimes you have private property lines that assume that the public land will always be in the same place. And so going forward, perhaps it’s putting conditions into permits or local coastal plans that acknowledge the fact that this boundary actually moves back and forth, and that it is actually moving inland with sea level rise. ... We could potentially limit these conflicts by requiring something to happen once the public trust moves into a private space.

But in situations where we don’t have that option, what other tools are available that would allow us to be a little more proactive? We need to think through that more. Part of what we struggle with as an agency is when we’re reactive, not proactive.

This is making me wonder, how does this moving boundary challenge our modern notions of property ownership?

Huckelbridge: That goes to the heart of this American vision of owning property, putting your stake down and passing it down for generations. This conflict is very Western. … The people who lived here before us did not have that struggle, and I think if we go back and learn some of the lessons that tribal people have been trying to teach us, we might have a better approach to these things.

It’s not in the settler mindset to think about land changing in this way, and our private property laws reflect that mindset. So how do we work within that framework or test that framework? The stark reality is that California is losing its beaches. And if we lose the ability to connect with the ocean, we lose so much of what California is about.

I’m thinking, too, that the more people are able to connect with nature, the more we will appreciate how everything is interrelated. The ocean doesn’t adhere to property lines or city-by-city boundaries.

Huckelbridge: I’ve been thinking a lot recently about settler culture, and how we’ve lost some of that connection to place. When you have spaces like we do in California — these big, open and beautiful natural places — you allow that connection to reestablish. This connection is so important, because it’s healing and you realize how important it is to protect these areas so that we can enjoy them in the future. I don’t want to have to tell my grandkids, “Sorry, we don’t get to go to the beach because we didn’t do a good enough job protecting it.”

Figuring out a way forward isn’t easy, like you said, because it’s really asking us to reconsider the way we think of the coast as a static landscape.

Huckelbridge: These conversations are difficult. The changes we are facing are scary. Let’s say you’re a homeowner who has a house on a bluff, and you may lose your home that you spent your whole life saving for — that’s a scary thing to talk about. But if we don’t talk about it, the consequences are worse. So I think we just have to lean in to that conflict and face it head on and try and understand that when we need to compromise, everybody’s going to have to give something.

That’s the only way we can get through it, is by figuring this out together. … We don’t have much time, and we just can’t afford to fail.

ONE MORE THING

This guest edition of Boiling Point would not be complete without a book recommendation, and as timing would have it, UC Press just published a new book on sea level rise this week:

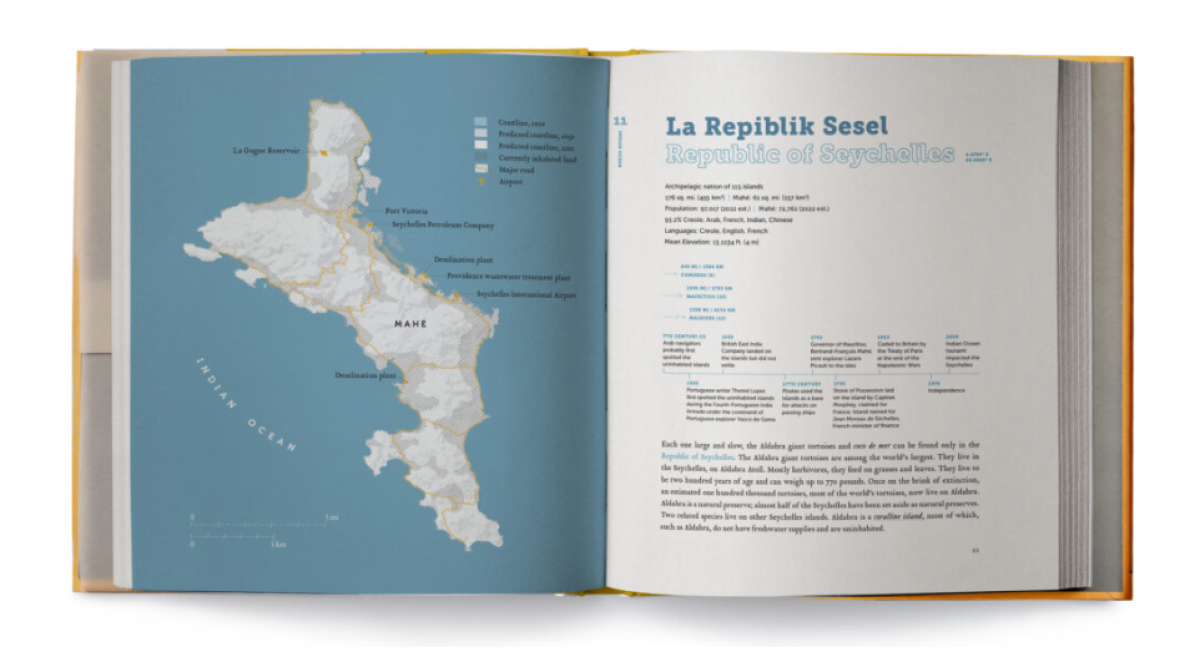

“Sea Change: An Atlas of Islands in a Rising Ocean,” by Christina Gerhardt, is a stunning examination of the maps we will have to redraw as the sea continues to rise. The book centers the voices of Indigenous Pacific and Black Caribbean communities, and it was recently named one of the “Best Popular Science Books of 2023” by New Scientist.

The book itself is a work of art, and Gerhardt, an environmental journalist who teaches at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa, weaves together quite a collection of essays, maps and poetry that invite us to rethink our relationship to these vanishing landscapes.

“How to make visible what might be geographically remote to some?” Gerhardt writes in her introduction. “How to encourage a thinking that is mindful of how we are all connected, as humans and with nonhumans?”

On that note, that’s it for today! Sammy Roth will be back in your inbox on Tuesday.

To view this newsletter in your Web browser, click here. And for more stories about our coast and ocean, follow me on Twitter and Instagram at @RosannaXia.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.