- Share via

The Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve suffers from many of the ills that might be expected of a natural area located in the middle of the nation’s second-largest city, including litter and even biohazards such as discarded needles from nearby drug use.

But on Saturday morning a few hundred volunteers had another culprit in their sights: Rhamphospermum nigrum, a nonnative plant better known as black mustard that has flourished in the 225-acre reserve and the wider Sepulveda Basin Recreation Area.

The plant, with its four-petaled yellow flowers in bloom, fills the basin’s meadows and paints a bucolic picture that belies what it really is — an invasive weed that crowds out native plants such as sage and poppy that are crucial to the health of the basin, its natural wildlife and the Los Angeles River that runs through it.

“It does look harmless, but it becomes a mono crop, and this is the main enemy to biodiversity,” said Dan Mott, environmental educator with Friends of the Los Angeles River, which held the event with the California Native Plant Society and San Fernando Valley Audubon Society. “The native species can’t be here, and all the birds and the insects that are supposed to be in this area, they don’t want the mustard.”

The grasslands also capture less carbon and aren’t as effective as native species in filtering runoff that enters the river, he said. The plant is native to North Africa, temperate regions of Europe and parts of Asia, and it is believed to have been introduced hundreds of years ago.

The environmental group has been conducting habitat restoration in the reserve since 2019, with this weekend’s event also a late celebration of Earth Day, after a prior event was rained out. On Saturday morning, the volunteers spent hours pulling up the black mustard, focusing on a patch of land with five large coast live oaks. The tree is native to California and resistant to fire, but not if surrounded by thick mustard weed undergrowth.

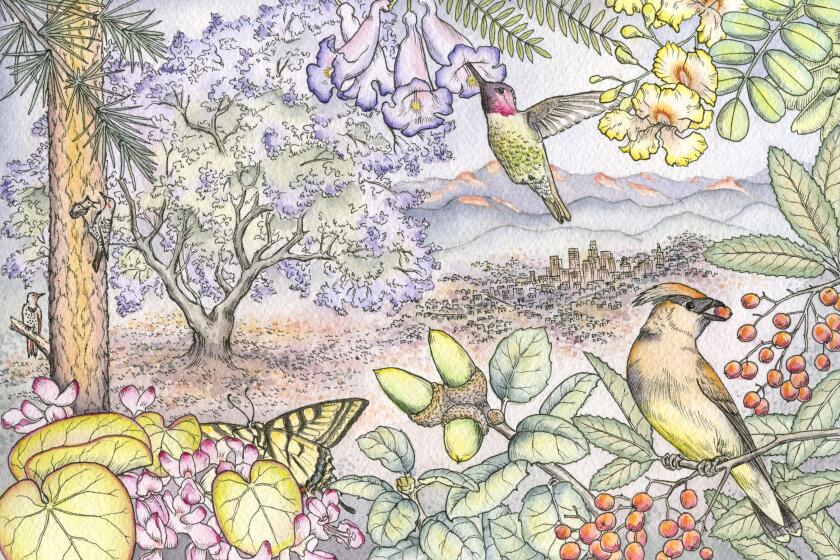

Jacarandas are pretty, but there are other L.A. trees to love: deodar cedar, coast live oak, Moreton Bay fig and more. Here’s how to spot and appreciate them.

“If there’s a bunch of invasive species creating fuel underneath it, it’s just kind of burning like a bonfire. It overwhelms the tree’s ability to protect itself,” said Mott, who figures that in five years crucial areas of the reserve should be largely cleared of the weed.

Wes Vahradian, 18, who has been volunteering with Friends of the Los Angeles River for four years, was serving as a volunteer leader and tracking how much habitat was being restored using ArcGIS, a web-based mapping software on his phone.

By 10:30 a.m., the app indicated that about a quarter of an acre had been restored. “We’ve done pretty solid here, and it’s just a great way for us to kind of measure the impact we’re making. We’ve done it all over the Sepulveda Basin,” he said.

Vahradian is entering his senior year at Campbell Hall, a private school in Studio City that requires students to engage in community service. Vahradian said he was attracted to the environmental group because he has long been fly-fishing in the river — “which is kind of crazy, but you can totally fish in it.”

He said that although the mustard weed does regrow, progress has been made over the years. “The whole premise is that the Sepulveda Basin is supposed to be a natural ecosystem, a place for birds when they’re migrating to come and take a break.”

The black mustard and other weeds that were pulled up was collected into 30-gallon paper garden bags that will be hauled away and buried in a landfill. Mott said the goal is to eventually compost the weed.

Zia Shaked, 11, who said her favorite activity was reading, had spent the morning with her mother stuffing five bags full of the mustard that had been uprooted by her younger brother and cousin.

“I learned that folding the weeds was really helpful before you put them in, because otherwise you get a mouthful of weeds in your face,” she said. “I was just putting the weeds in the bag. I didn’t even notice how much space that was cleared up and I looked up, like maybe a half an hour later.”

Melanie Winter has long advocated for change along the L.A. River. As she undergoes cancer treatment, she remains focused on healing L.A.’s relationship to water.

Shanna Shaked, the girl’s mother, said this was the second time the Santa Monica family had been out restoring habitat, though it was the first time for her daughter.

“It felt like a really good way to spend the morning, to be outside and doing something that felt helpful for nature,” said Shaked, an adjunct professor at UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability. “It was a team effort.”

Mott said that the habitat restoration events typically draw about 150 to 200 participants but he has definitely noticed an uptick in attendance since the Jan. 7 fires that devastated Pacific Palisades, Altadena and other communities.

“I think there was this powerless feeling when the wildfires were happening. You know, we can’t go out there and fight fires ourselves, but this work is actually preventing the spread of wildfires. It’s just something physical, tangible you can do to help the community and help with that problem,” he said.