Jess Jackson led winery by example

- Share via

Jess Jackson, who founded Kendall-Jackson Winery in 1982, died last week at the age of 81, leaving an almost incalculable legacy on the California wine industry. He transformed it at least twice, first in establishing a style of wine that would come to be as much an irresistible flavor profile as a cultural icon; he would go on to become one of the state’s most passionate and articulate advocates for the preeminence of place in the production of great California wine. In the process, he became one of the industry’s most envied property owners, and by far one of its richest men.

Jess Jackson was born in Los Angeles in 1930 and raised during the Depression in San Francisco. His most formative days, he liked to tell people, were those spent on his grandfather’s farm in Colorado, which instilled in him an abiding love for the land, as well as for horses — which no doubt led to the passion for racehorses that would consume him in his later years. After a career as an attorney in San Francisco, Jackson purchased a pear and walnut orchard in Lake County, Calif., which he converted to grapes in 1974. Eight years later, his Chardonnay crop went unsold, and Jackson decided to bottle 20,000 cases himself.

Jackson would go on to establish a fail-safe formula for his wines: premium wines without a premium address, vintage wines that betrayed no vintage variation, a brand as consistent as Lipton’s tea. He did this by drawing from vineyards all over California to gather what amounted a “palette” of California flavors with which to craft his blends — marrying the citrus notes of Monterey fruit, say, with the more tropical notes of Santa Maria, resulting in a more complex, satisfying wine. Kendall-Jackson’s Vintner’s Reserve Chardonnay became a kind of masterpiece of quality-for-price, a fruit-forward wine with soft, honeyed flavors and a pronounced hint of sweetness, as luminous as California sunshine. Not everyone cared for this simple, overtly confectionary style, but it became a huge success, setting the style for American Chardonnay for decades and converting millions of Americans into wine drinkers.

Jackson’s success with the brand enabled him to go even further with the concept; in time he was able to convert nearly his entire production to estate vineyards, giving him unprecedented control of farming and fruit quality. He assembled one of the most impressive collections of vineyard property in the world, more than 10,000 acres under vine across the state, as well as a stable of blue-chip brands, including Cardinale, Lokoya, Hartford Court, Matanzas Creek, Arrowood, Cambria and La Crema — an annual production of about 5 million cases (of which approximately 3 million cases come from Kendall-Jackson).

“He realized early on that the power of a wine brand was in the land that supplied that brand,” says one of his winemakers, Chris Carpenter of Cardinale and Lokoya. “To control that land and have a steady source of high-quality raw product to make those wines was of the utmost importance.”

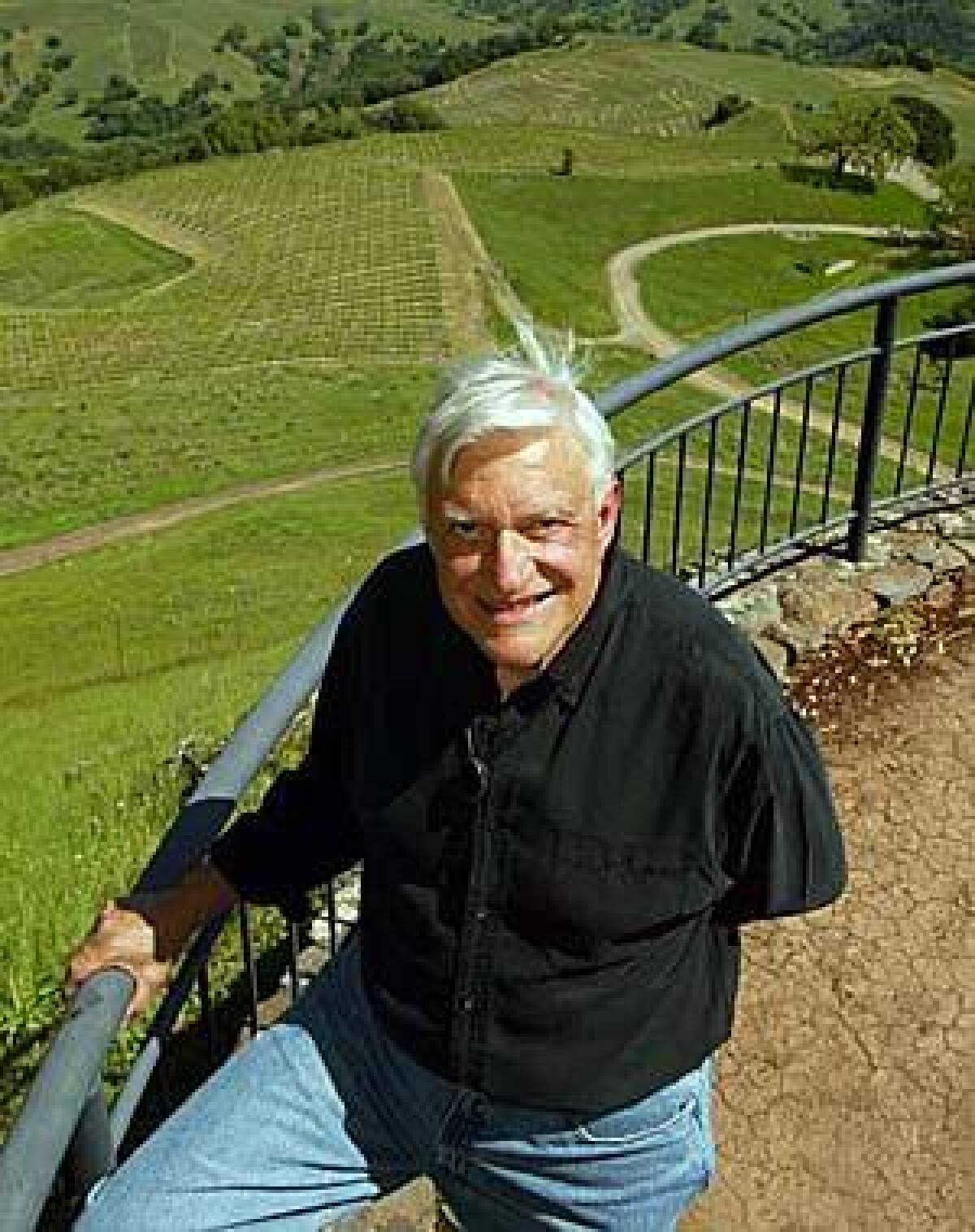

I met Jackson on a spring day in 2003, when he served as my guide on a mildly harrowing helicopter tour to admire some of his many North Coast properties. To look at him on the helipad he seemed indestructible — tall, broad-shouldered, barrel-chested, with bright hazel eyes and an easy smile — he had a deep, dulcet-toned voice and a lawyer’s mastery of it, and a handshake so powerful it seemed he just might take you down with it.

We took off in the Russian River Valley, hurtling up the Sonoma coast before cutting inland to the company’s impressive high-elevation vineyards in the Alexander Valley, set on ridges so vertiginous it seemed as if the pilot might have a hard time finding a place to land. We toured a half-dozen properties that day, and with characteristic ebullience he spoke of each with a level of detail that astounded us; it would be hard to overstate the pride he exhibited in these estates and the depth of his conviction that they were among the greatest in California.

Jackson managed his company well into his 70s, long after his so-called retirement, an event he announced to almost no effect 11 years ago. In the last decade he developed especially strong connections with his winemakers. “It seemed like Jess had a much broader sense of what we do,” says Carpenter, “and wanted us to understand how we impact everything he did in his organization.”

In his countless discussions with his boss, Kendall-Jackson winemaster Randy Ullom notes how Jackson would never be satisfied. “It was always, ‘Well, that was last year. What are you going to do to make it better this year?’” He was always ready with specific suggestions, including vine spacing and oak regimes. Ullom recalls often going silent in meetings, trying to work out the challenge Jackson had just presented him with. “He’d be there grinning, and eventually he’d say, ‘Just try it. See what happens.’ You always walked out of the room with a lot more work to do but with the energy to do it too.”

Not that that was always easy. “He never stayed on the same path for long,” Carpenter says. “We’d get all revved up going one way, and then he’d have some eureka moment, and the next day you were going another. But he was such a presence, and he had such a great track record that you were bound to stick with him.”

For now the employees of Jackson Family Wines are coping with the loss of that presence, of a leader who guided and inspired them daily, even in his final days. “We’ve all been used to him leading the charge,” says Gilian Handelman, the company’s director of wine education. “It’s been inspiring to work for a person with vision, instead of an organization.”

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.