Discovering the foods of Paris’ Little Africa

- Share via

Africa in Paris, saving a Salvadoran street market, savoring Filipino roasts and stir-fries, tomato soup protest and the coming of Langer’s Godzilla pastrami. I’m Laurie Ochoa, general manager of Food coverage at the L.A. Times, back in Los Angeles after a trip to France and Italy, with this week’s Tasting Notes.

Paris’ Drop of Gold

The Paris neighborhood La Goutte d’Or (the Drop of Gold) is just a 20-minute Uber ride from the Louvre and about 23 minutes on the Metro. It’s even closer if you start from Montmartre’s Sacré-Cœur basilica — a quick 13-minute walk through the 18th Arrondissement. Yet as Jacqueline Ngo Mpii, founder of the community center, gallery and boutique Little Africa Village, said on a cool fall morning, few visitors bother to check out one of of Paris’ most fascinating food neighborhoods.

I had the chance to join a walking tour of the African quarter with Ngo Mpii, the force behind the excellent guidebook “Africa in Paris,” and right away came across produce varieties you aren’t likely to encounter at the wonderful but more mainstream Marché President Wilson. There were displays of deep purple-hued safou fruit, like elongated avocado, as well as manioc (also known as cassava or yuca) stacked as abundantly as firewood, boxes of multicolored habaneros, ripe and unripe plantains and much more in between the butchery and fish shops.

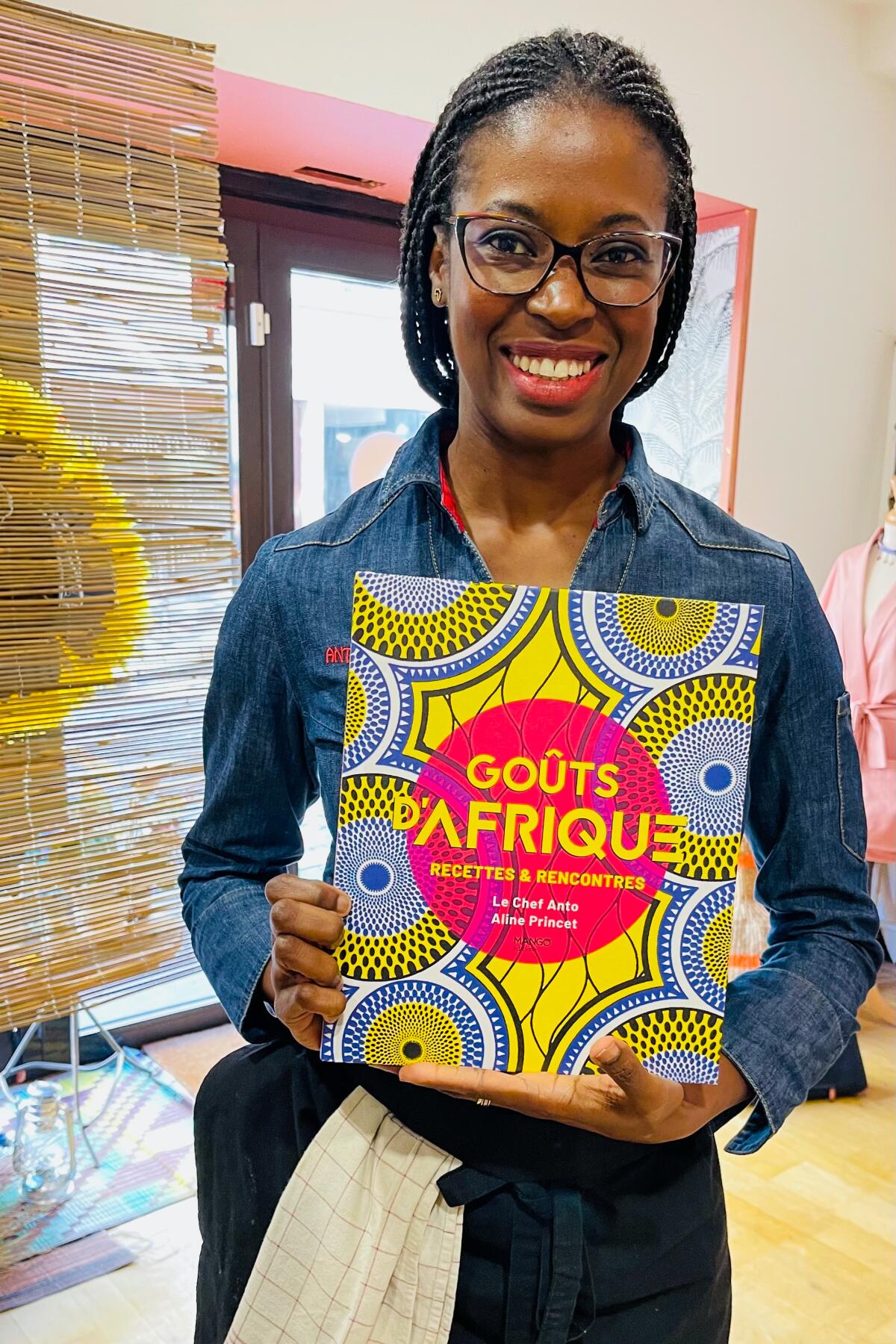

Inside the carefully curated spice-and-grocery shop Épicerie Ivoirienne Marché de Dabou on Rue des Poissonniers, we sipped baobob juice, checked out the many spices and grains and met chef and TV personality Anto Cocagne, whose cookbook “Saka Saka: Adventures in African Cooking, South of the Sahara” came out in English earlier this year.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Ngo Mpii and Cocagne both talked about their love of red palm oil, which they consider wholly different from the environmentally destructive filtered palm oil that appears in processed foods like Nutella. (For more about palm oil, read Jocelyn Zuckerman’s excellent “Planet Palm: How Palm Oil Ended up in Everything ― and Endangered the World.”) We ended our tour with lunch at Little Africa Village, where Cocagne made a gorgeous dessert of roasted spiced pineapple with a crumble made from ground cassava, which happens to be gluten-free. (The recipe is in Cocagne’s cookbook.)

Even though we have concentrations of Ethiopian restaurants in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., it’s a rare thing to be in a neighborhood with so many countries of the African diaspora represented. African flavors are finding their way into Michelin-level restaurants too. One of Paris’ hardest reservations is Mosuke, the one-star restaurant run by the French-born Mory Sacko, who brings the flavors and influences of his West African heritage (Mali, Ivory Coast and Senegal) into his modern French cuisine. Seeing Paris through Ngo Mpii’s eyes makes the city’s culinary landscape even richer and more exciting.

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Have a question?

The fight for a Salvadoran street market

With a variety of foods including fried yucca and blood-clam ceviche, the 50 or so Los Angeles vendors at the Salvadoran street market — a fixture for more than 20 years along Vermont Avenue’s El Salvador Community Corridor — provide a taste of home for writer Karla Tatiana Vasquez and thousands of others. But the market has been under stress for the past few months following a city-led closure in May as part of a “clean-up and beautification project.”

Since then, as Vasquez reports, the vendors have struggled to regroup. “The case is a classic battle of negotiation over public space in urban Los Angeles. Despite the city’s embrace of immigrant cuisines and the efforts from nonprofits, organizers, petitions and legislation to legalize street vending, this is a repeated pattern reminiscent of so many chapters in L.A.’s history: The Lincoln Heights Avenue 26 night market, the Leimert Park Village Vendors and the South Central Farm closure all come to mind,” Vasquez writes.

“We are not asking them to give us” a handout, vendor Rebecca Mendez said to Vasquez. “The only thing we ask is that they let us work.”

Kuya Lord’s tray chic

In his review this week of chef Lord Maynard Llera’s pop-up turned Melrose Avenue restaurant, Kuya Lord, Times restaurant critic Bill Addison says the flavors “drift between herbal subtlety and high-potency doses of sour, salt and fermented umami.” The restaurant, which began during the pandemic in the garage of Llera’s La Cañada Flintridge home, “is the culmination of Llera’s deferred dream,” Addison writes. On the day the review came out, I stopped by Kuya Lord for a working lunch with food editor Daniel Hernandez and deputy food editor Betty Hallock. It was exciting for us to see Llera in action as people lined up for trays of porchetta-like lucenachon, prawns and terrific hiramasa, or yellowtail collar. The trays would make an easy and delicious family dinner, but it’s also fun to sit at one of Kuya Lord’s tables in the late afternoon basking in the garlic-infused scents coming from the kitchen and talking with friends.

Tableside service and pink sauce

In her weekly report on what she’s been eating, Jenn Harris extols the retro seafood vibes of Dear Jane’s, the companion restaurant to Dear John’s steakhouse from Hans and Patti Röckenwagner and Josiah Citrin. High on her must-try list is the shrimp Louie, a dish I always love at Hollywood’s Musso and Frank (when I’m not ordering an avocado cocktail and sand dabs). At Dear Jane’s in Marina del Rey, the Louis is made tableside and features a “Thousand Island-adjacent” dressing — a pink sauce that Harris says is worth seeking out. What makes the sauce so good? In part, a key untraditional ingredient that chef Ken Takayama revealed to Harris: diced, pickled jalapeños.

Dim sum questions and answers

In this week’s episode of Season 2 of “The Bucket List,” Jenn Harris’ dumpling series takes us into the world of dim sum. She orders a tableful at Sea Harbour in Rosemead and gets a behind-the-scenes look at the making of har gow and shumai with Lunasia chef Woo Yip. In the process, she gets answers to pressing dim sum questions, such as: Why are shumai kept open rather than folded closed like most other dumplings?

Protest tomato splat

Throwing tomatoes, whole or, as we saw this week, pureed into soup, has been a go-to expression of protest for centuries. Friday morning brought the latest example when an activist advocating for meaningful climate policies dumped what looked like tomato soup — or possibly tomato sauce — onto a fellow activist who tried to glue his head to the glass frame holding Johannes Vermeer’s masterpiece “Girl With a Pearl Earring.”

The art attack came less than a week after activists threw mashed potatoes at Claude Monet’s “Les Meules (Haystacks)” in Germany’s Museum Barberini and an earlier tomato-soup dump on Vincent van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” at London’s National Gallery. Are the soup attacks an Andy Warhol homage?

It all brought to mind a 2014 story by Rochelle Bilow in Bon Appetit about the history of foods of protest.

“My guess is that people throw food because it is cheap, visible and easily accessible,” Columbia political science professor Andrew Gelman told Bilow. “Tomatoes are inexpensive, easy to throw and make a satisfying splat.”

Godzilla pastrami

Finally ... we rarely need an excuse to go to Langer’s, but to celebrate Godzilla Day on Nov. 3, the deli is teaming up with Toho International, the U.S. branch of the Japanese studio, to offer a new Godzilla-size pastrami meal — called the No. 68 in honor of the movie monster’s 68th anniversary. The $68 meal, which comes with unlimited fries and soft drinks, will be available Oct. 31 through Nov. 5.

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.