Kerry Prepares for His Big Night

- Share via

BOSTON — With his speech to the Democratic National Convention looming hours away, Sen. John F. Kerry, now the official Democratic presidential nominee, spent today largely out of sight, a private pause in a most public moment.

Advisors said he would deliver an address aimed primarily at weaving an evocative portrait of his life, hoping to give voters a better sense of who he is and what he would do for the country.

Leaning heavily on his service in Vietnam, the senator from Massachusetts would attempt to showcase himself as someone of courage and steadfastness, using his biography to make a case for his personal attributes, they said.

Excerpts of Kerry’s speech released this afternoon by his campaign show that the candidate is going to reprise many of the lines he uses in his stump speech.

“We’re the can-do people,” is in there, as is the standard that Kerry says he would demand as commander in chief: “The United States of America never goes to war because we want to, we only go to war because we have to.”

It appears the candidate is going to pepper his speech with the word “values,” as he does regularly on the campaign trail.

“Values are not just words,” Kerry will say, according to the excerpts. “They’re what we live by. They’re about the causes we champion and the people we fight for.”

While Kerry will lay out his specific proposals about job creation, energy alternatives, and national security, aides said his speech would not break new policy ground. Rather, the candidate will try to communicate his values by touting the decisions he’s made over the course of his life.

The thrust of the speech acknowledges a challenge facing the Democratic nominee as he heads into the fall: that while the country is evenly divided, many voters say they still do not have a good sense of who John Kerry is.

Kerry labored over the bulk of his address, scratching it out in longhand on legal-size paper in hotel rooms and during airplane flights. While he had the assistance of several speechwriters — including Robert Shrum, a longtime Democratic strategist and wordsmith — Kerry wanted to determine its content and tone.

As he began writing in earnest four weeks ago, he mulled over the writings of Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt. He thought over Revolutionary War history, and reread letters his father wrote his mother.

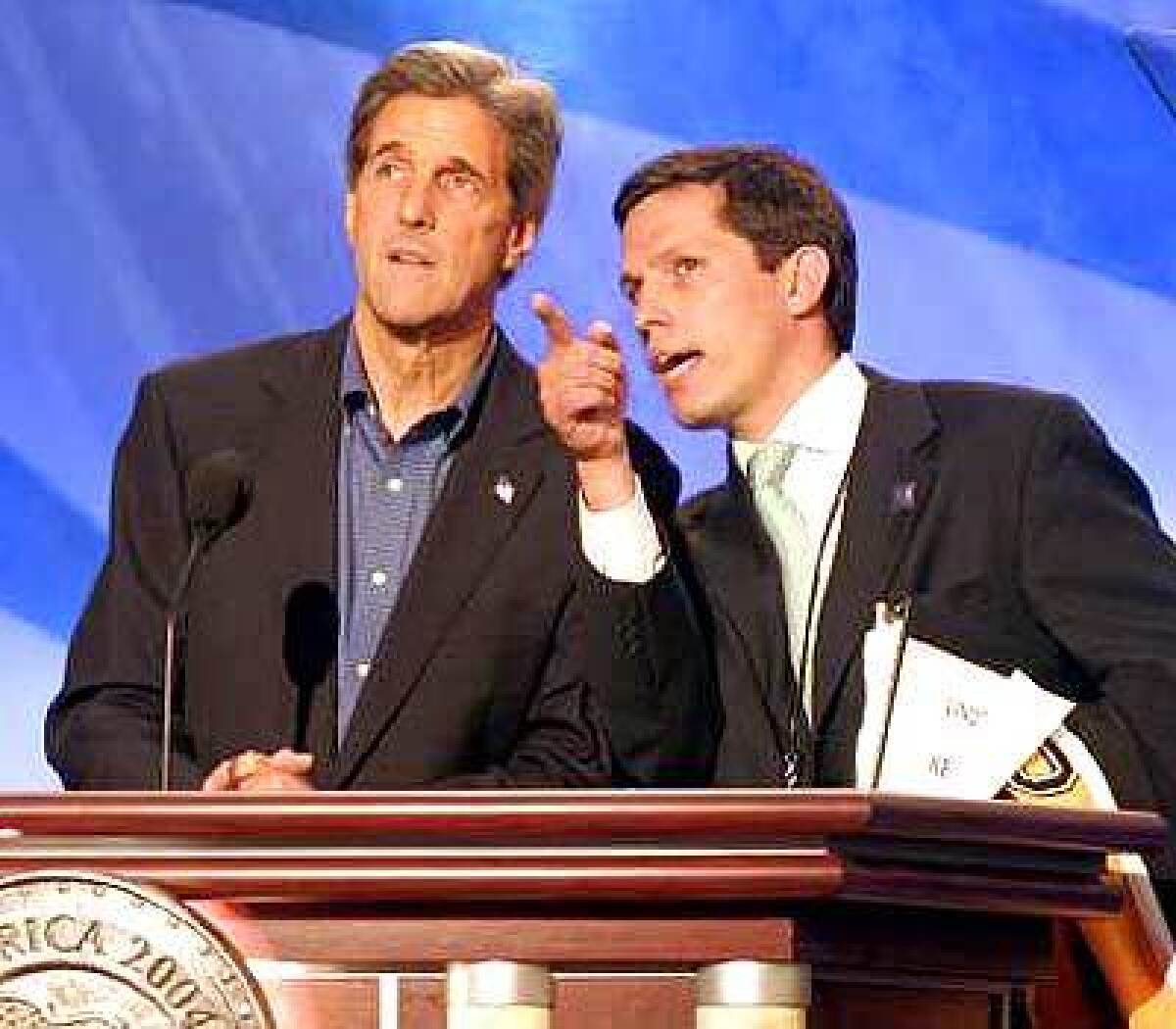

He emerged at midday from his red brick townhouse on Louisburg Square in the fashionable Beacon Hill section of Boston to visit the FleetCenter, site of the convention.

There, he spent about 12 minutes on the podium, performing what has become a speech-day convention ritual: a check of the technical equipment — the sound system, the lights, the height of the all-important TelePrompTer — that also allows the candidate to become familiar with the hall and the huge podium before he walks out to deliver the speech that, to date, is the most important of his campaign.

The speech accepting the nomination has historically gained the biggest audience of the convention, and in the case of the challenging candidate, is the best opportunity to introduce himself to the broadest number of Americans, many of whom have presumably not been paying close attention to the presidential race.

In Kerry’s case, it is an opportunity to present himself in a way that counters the Republican effort to portray him as someone who waffles on the crucial issues and lacks the resolve to be commander in chief.

Kerry projected a relaxed demeanor during his visit to the podium.

“Testing,” he said. He paused. Then, spying a clutch of reporters on the arena floor beneath him, he declared: “Members of the Fourth Estate, I have called you here to tell you that your reign is over.”

The candidate was dressed in the uniform of “Kerry informal”: A navy blue blazer, a lighter blue shirt and gray slacks. Some supporters applauded when he walked onto the podium. He carried a water bottle and placed it on the lectern as he scanned the scene.

As the reporters sought to pepper him with questions, he said, “I can’t hear a word you’re saying. What?” Then, he pronounced himself content with the setting: “This is great,” he said. “Can we do it now? God, this is a great, a great hall.”

Asked whether he was nervous about the speech, or ready to deliver it, he said, “I’m really looking forward to it. I feel terrific.” With that, he began silently mouthing words, punctuating his silence with the dramatic gestures — the fist pumped in the air, the finger pointing outward, and the arms outstretched toward an imaginary crowd — that speakers use to underline their points.

His exercise over, he headed off stage.

Later, he took out his bicycle, a high-end road bike, and, outfitted in yellow and black helmet, white T-shirt and dark shorts, spun along the Charles River Esplanade.

A bystander called out: “Cars are weapons of mass destruction.”

The candidate-biker whizzed past.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.