Alive and well

- Share via

Ten years ago, cultural commentators found it fashionable to forecast the death of classical music. That bit of silliness ended on Sept. 5, 2000, with an unlikely work by an unlikely composer in an unlikely place. The Stuttgart Bach Academy in Germany commissioned four composers from different cultures to write new passions on each of the four Gospels. The third work, devoted to St. Mark, was by Osvaldo Golijov, an Argentine of Jewish Eastern European descent who had studied in Israel and Pennsylvania and settled in the Boston area.

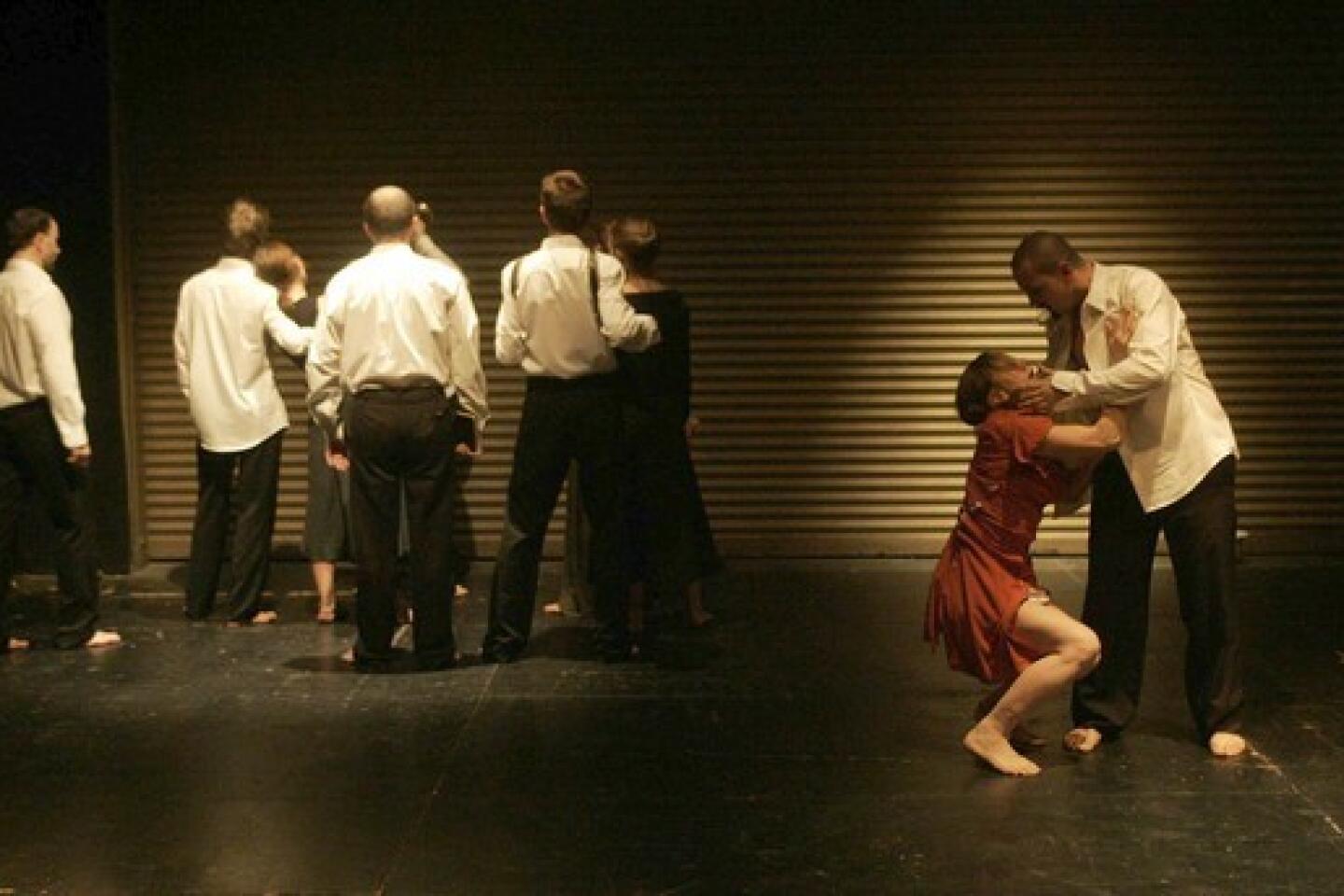

Golijov used what felt right, which meant flamenco and rumba, Cuban drums and a Brazilian jazz singer, a Capoeira dancer and a rocking Venezuelan choir. The stiff Stuttgart Bach crowd sat in stony silence throughout the 90-minute premiere. But when it ended, there was wild cheering and foot stomping for 20 unforgettable minutes.

“La Pasión Según San Marco” became an immediate global hit and is now a classic (a new recording is scheduled for March, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic will perform it in April). It was hardly the first attempt at multicultural, polystylistic crossover global music. In the second half of the 20th century, Asia had already become a major player in Western classical music. Russians such as Alfred Schnittke were mining combinations of styles in new ways. North American composers had been in the eclecticism business for decades.

There was something different, though, about Golijov’s “San Marco.” It didn’t sound self-consciously multiethnic, it merely sounded natural. And now, a decade later, the global implications are clear. Western classical music may be run out of Europe and the U.S. but it is fed from everywhere, be it Reykjavik or Beijing. Critics are starting to call a certain Venezuelan conductor trained far from the capitals of European culture the most significant music story of the decade.

A second starred date was, particularly for Angelenos but also for classical music in general, Oct. 23, 2003. Walt Disney Concert Hall opened. For some time it had been clear that Los Angeles was breathing new energy into classical music, but now the city had a new icon, and it was a rhapsodic building made for the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

If Disney Hall’s symbolism was important, its implications were even more important. Frank Gehry’s architecture demanded music of our time, and the Philharmonic, under Esa-Pekka Salonen, took this as a challenge to continually push the boundaries. The New York Philharmonic is one of many organizations now paying close attention.

Along with the talk of classical music’s demise at last century’s end was the doomsayer prediction of the inevitable collapse of the recording industry. In 1999, the year 2000 was seen as the end of the line. It didn’t happen. On New Year’s Eve 2000, the date got pushed back to 2001. Then 2002, 2003, 2004. . . . We’re waiting. In 1999, too many CDs to contemplate were released. In 2009, too many CDs to contemplate were released.

Things, obviously, have been changing. Retail has moved mostly to the Web. The classical market has branched out to DVDs and downloads. The slack left from fewer major label releases has been picked up by artists themselves, since technology has empowered them to produce their own CDs and DVDs relatively easily. In the ‘90s, keeping up with the prolific Philip Glass was not easy. Now that he runs his own label, he’s been releasing CDs of recent and past works practically every month or two.

The implications of the digital wonderland, to use comedian Harry Shearer’s term, remain to be seen. The Berlin Philharmonic has begun a digital concert hall whereby for a fee you can “attend” its concerts on your computer, if virtual music is to your taste. The Metropolitan Opera has entered the cineplex, popcorn and all. Internet radio puts the world on our laptops, especially given the vast amount of live performance that is broadcast by state-run European radio stations.

Not I, nor anyone else, can tell you where we are headed, and don’t believe anyone who flaunts surveys. Audiences may be diminishing in rural America, but in the last 10 years, there was more music made by more people and delivered in more accessible ways to more places and at higher quality than ever before. We should only be so resourceful when it comes to feeding the world’s population or saving the planet.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.