Thoroughly modern tribal

- Share via

Bob WEIS was trolling EBay from his 1962 Palm Springs ranch house, hunting for the African artifacts he has collected for the last 20 years, when he hit the mother lode. There, among the carved wooden stools and ceremonial figures, hand-woven textiles, beaded masks and metal currency in the shape of swords, was an early 20th century bronze mask with two faces from Gabon.

After winning the auction, Weis e-mailed the seller, a South Carolina man who had happened upon the treasure and 200 other African objects in a storage locker he had purchased for its other contents — a lawn mower and a smoker grill. From photographs of the cache, Weis could make out horned figures from the Songye tribe of Congo that has long been his obsession. Weis took a deep breath and wrote a check in the four figures for the entire inventory. The score doubled his collection, filling nearly every surface in his three-bedroom home.

It’s hardly surprising that in Palm Springs and Los Angeles, as with other cities caught in the grip of midcentury madness, the arts and crafts of Africa are experiencing a revival in home décor. The work, Weis contends, resonates with the spirit of Modernism: the reduction and abstraction of shapes in which form follows function. The primitive wood carving and metalsmithing from Africa exudes a sculptural purity of form that adds drama and a sense of history to 20th century architecture.

Though they were popular trophies from safaris in the 1920s, a home décor fad in the beatnik 1950s and an expression of black-is-beautiful cultural pride in the 1970s, African ritual and domestic objects cast a different spell on today’s designers. In the cover story of the November-December issue of Metropolitan Home, Arthur Dunnam’s design for a Park Avenue apartment integrates tribal masks with Art Deco and French furniture, including a contemporary table wrapped in rope by the Parisian designer Christian Astuguevieille, whose work, Dunnam says, “is very much influenced by African art.”

“From the 1920s onward, when you look at photos of the chic interiors of sophisticated travelers, you will see African artifacts,” Dunnam says. “Though the look is certainly becoming more commonplace, I don’t consider it a trend. It has always been an iconographic part of cosmopolitan 20th century design because people with an appreciation for modern art and a sense of style tend to have African art among their personal possessions.” Decorators who have ripped their way through continental European, Middle and Far Eastern inspirations are also looking at African furniture and tapestries as a visual counterpoint. At the 20th century furniture gallery Pegaso International on La Cienega Boulevard, beaded bride and groom headdresses adorned with birds perch on Italian tables. The juxtaposition works not only with streamlined minimalism but also with embellished period styles.The latter is a mix that defines the Los Angeles home of actress Alfre Woodard, who has collected East African artifacts and contemporary South African art for two decades. “My father was a decorator who did a lot of homes in traditional French antiques, and I like the formality and shape of that furniture,” she says. Indeed, Woodard has gilded chairs, painted Italian tables and silk-covered banquettes. “But the things that I am most attracted to,” she adds, “are those in which you can feel the presence of the artists who created or the people who owned them.”

Ever since the first shields, masks, tools and textiles made their way from colonized African nations to the museums of European capitals in the early 1900s, these objects have helped redefine figurative art and graphic design. Picasso’s 1907 masterwork “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” twists the human face into a replica of an African mask, and the seemingly random squiggles found on ancient Kuba cloth from the Congo are instantly recognizable in the later paper cuts of Henri Matisse and the post-Pop work of Keith Haring.

That interconnectedness is the guiding spirit at Lacy Primitive and Fine Art in Los Angeles. The Melrose Place gallery opened five years ago and exhibits tribal pieces side by side with canvases and sculptural totems by contemporary abstract expressionists such as C. Gregory Gummersall. The most prized African objects are more likely to be treated as museum pieces. “Slowly but surely, everything in Africa is changing,” says Lee Lacy, the Lacy gallery’s director. “Young people are moving to the cities, and as tribal traditions disappear, the art ceases to exist.” For that reason, he adds, pieces made for actual use instead of for the tourist trade are more valuable.

Because most of the craftsmen are anonymous, the more precisely a piece can be traced to a particular region and tribal craftsman, the more it is worth. At Sotheby’s May auction of African, Oceanic and pre-Columbian art, an early 20th century wooden bowl attributed to a Yoruba tribesman known as “Olowe of Ise” sold for $534,400.

“Collectors are intrigued by African art for what it represents culturally and historically as much as they are attracted to its aesthetic simplicity of form,” says Jean Fritts, Sotheby’s worldwide director of African and Oceanic art. The auction house has noted an increase in new collectors and added two African sales to its annual auction schedule in Paris, where more than 40 galleries specialize in tribal work.

The renewed interest in African art is not limited to the rarefied air of auction houses, galleries, high-end antique stores and collectors’ homes. Since 1983, Ernie Wolfe — who runs an eponymous African art gallery out of the downstairs of the 4,200-square-foot building in Los Angeles where he also lives — has seen a shift in interest and inventory from museum-quality ceremonial pieces to functional goods.

“For under $5,000,” he says, “you can get a hand-beaded colonial club chair from Nigeria, and for $500 you can get currency from the Mbole people that looks like a 3-D version of the Chanel logo.”

In most large cities, contemporary crafts from Ghana and other nations can be found for much less at African boutiques and street fairs. “Some people just want a nice decorative mask and don’t care about its authenticity,” says Weis. “It could be made in Europe or Asia to resemble something African, and they’re perfectly happy with it.”

Last year, the National Geographic Society acknowledged the trend when it licensed its name to eight manufacturers of household items, including Lane furniture, Sferra Bros. linens and California furniture and accessories company Palecek.

The society, which has made several documentaries about Africa, “saw this as a way to celebrate the recognizable and beautiful crafts of Africa” while extending its educational mission, says Krista Newberry, vice president of licensing. Profits support the study and preservation of indigenous societies.

In addition to products made to look tribal, the African art now being collected includes contemporary sculpture and painting created for its own sake. Africa’s fine art explosion, Wolfe says, “is just the bomb right now. For the first time, Africans have the economic and political freedom to express themselves without having to be sign painters.”

In the early ‘90s, Wolfe began amassing a collection of commercial signboards and figurative paintings on grain sacks used to advertise movies. These paintings are as integral a part of Wolfe’s home life as the African antiques that fill his loftlike gallery and home at Sawtelle and Santa Monica boulevards.

As he dishes out lobster that he caught to his wife, Diane, and their sons, Russell, 10, and Ernest, 13, Wolfe points to a favorite piece from Ghana. Propped in the corner of the downstairs dining room crammed with ancient ladders and 19th century bookcases laden with archeological pottery is an enormous hand-painted lobster. It looks like a prop from a sci-fi flick about radioactive crustaceans, but the midsection opens to reveal that it is a casket.

The Smithsonian has tried to buy the piece “a number of times,” Wolfe says. In keeping with the African tradition of customizing a coffin to reflect the occupant’s occupation, lobster hunter Wolfe would like to have his ashes placed in the belly of the beast. Until such time, says Wolfe, “It is my personal shrine. I wouldn’t say that I pray there, but on occasion I find myself speaking to the coffin before I go diving for lobsters.”

On his first trip to Kenya, in 1973, Wolfe, 54, bought a neck rest and some containers “because they were very beautiful and seemed so authentic and traditional I couldn’t believe they still existed.” He has returned to Africa more than 40 times since.

Living with rare objects has hardly made the Wolfe pack precious about their collection. “Because we don’t have a yard, our kids learned to ride their bikes by practicing in the gallery,” Wolfe says. Birthday parties and “feasts of the harvests” are held at the 14-foot refectory table surrounded by coin-decorated wooden chairs from Liberia and covered in African whistles, walking sticks, dolls and daggers. “When people come to visit, it’s festive,” he adds.

“The dinners sometimes get a little boisterous,” Diane Wolfe admits. “We had a guest, a doctor friend of ours, pick up a ceremonial knife and start cutting his wild boar chop with it.” Diane doesn’t reach for a coaster when a guest puts down a Diet Coke on a 1940s Senufo wooden bed from the Ivory Coast that serves as a coffee table. “The great thing about African furniture,” she notes, “is that whatever happens to them then becomes part of the patina.”

In Woodard’s home, low seats from the Ivory Coast sit in stark contrast to a gilded chair by Los Angeles designer Rose Tarlow. It is the stools, not the decorator throne, she says, that have “the nobility. When I touch the chairs that the elders sat in, I feel like they’re alive. I feel warmth and the deep energy of continuity.”

Woodard became a serious collector of tribal artifacts after acquiring contemporary Shona sculptures from Zimbabwe during the filming of the 1987 TV film “Mandela.” In her Santa Monica abode — a concrete structure warmed by glyphs, hand-painted walls, silk drapes and the vivacity of the actress and her two children, Mavis, 13, and Duncan, 10 — Woodard favors the work of South African painter Vusi Khumalo.

She often pauses to contemplate Khumalo’s 1995 landscape of a township, a multimedia work made from paint and tin cans that her husband, writer-producer Roderick Spencer, found in the basement of a community center outside Johannesburg. Now it hangs in their dining room, where Neoclassical chairs surround a table covered in an Indian sari.

A frequent visitor to the Ernie Wolfe Gallery, as a client and a friend, Woodard also has a hands-on approach to collecting. “We use everything,” she says of her African furniture, which includes a wooden bed employed as a coffee table on the patio. Throughout her home, the African influence is artfully combined with more traditional elements to create a worldly environment.

In the living room, silver English andirons from an antiquarian on London’s Portobello Road gleam in an adobe walled fireplace crowned with a mantel exhibiting South African ceramics covered in woven black and white telephone wires. An Ethiopian mask sits under a modernist zebra made of wire by African American sculptor Dale Edwards. “It is a multicultural house, with a basis in Africa,” Woodard explains. “I didn’t realize how much so until I looked at how many pieces I have and love. That’s when I knew I was a collector.”

Larry Lazzaro knew that Bob Weis was a collector from the get-go. When the couple first met in New York’s East Village, Weis had already filled a tiny studio apartment with artifacts, an interest developed in part by the African influences he had seen in then contemporary art stars Keith Haring and Jean Michel Basquiat.

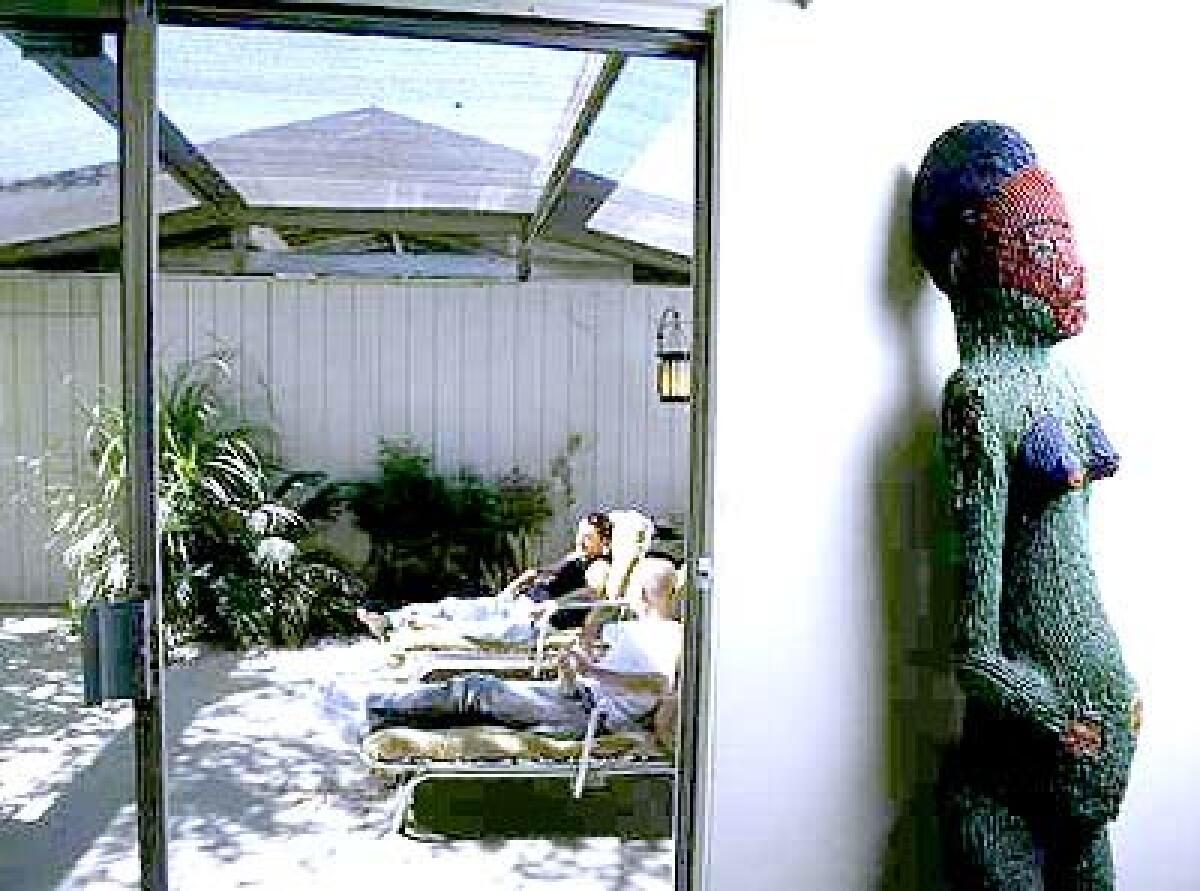

When Weis, a composer of avant-garde soundscapes, and Lazzaro, a business advisor, purchased their midcentury fixer-upper in 2000, there was little doubt what it would become. Inside, the only hint of the modernism for which Palm Springs has become famous is a free-standing white enameled genie-bottle fireplace and a collection of thrift-shop furniture on linoleum-tiled floors.

Almost everything else, with the exception of 21st century electronics, came out of Africa. A beaded elephant mask from Cameroon stands sentry by the front door, which opens to a slate foyer lined with metal staffs and ancient African currency that looks like 6-foot Brancusi sculptures. Ceremonial gold foil crowns surround a flat-screen TV in the bedroom, and power figures studded with nails and metal scraps surround machines in the home office.

“At first I tried to rein him in,” says Lazzaro. “I was always asking, ‘Do you really need this?’ ”

While unpacking his haul after the EBay windfall, Weis realized that what was once a hobby now could be a calling. He is mounting an exhibition of African textiles at Modern Tribal, his fledgling gallery in Palm Springs.

Lazzaro already had become a convert. “When I walk through our house, I can feel the power of these pieces and what they represent,” he says. “Their spirit takes me out of the cellphone world to a plane on which everything in life was connected.”

Weis and Lazzaro even share their living room with the dead. Under the light of a floor lamp that sprouts tentacles, a flea-market console serves as a small altar for 13 gleaming reliquaries from the Kota tribe of Gabon. Resembling small Cubist statues, these brass- and copper-covered funeral effigies of dead tribesmen hold bundles filled with bone fragments of the deceased.

The 13 “guests,” as Weis refers to them, began arriving after he saw a 2003 exhibition of reliquaries in Paris. They are a bittersweet prize, reminders that war, genocide, famine and AIDS have brought many African artifacts to the market. “They are the most personal family objects that exist,” says Weis. “And the fact that they are being sold for food and medicine is heartbreaking.”

As a result, Weis and Lazzaro consider themselves merely custodians of the funerary artifacts. “It might sound a bit wacko,” Weis admits, “but when they arrive, we light incense and have a ceremony, welcoming them into our home.”

*

David A. Keeps can be reached at home@latimes.com.

*(Begin Text of Infobox)

Shopping for that African look

*

These websites and Southern California retail sources carry some of the more popular African items on the market. Products include contemporary arts and crafts, items inspired by African art, and artifacts and antiquities.

Old and new: Wooden beds from Ivory Coast, beaded chairs from Nigeria, 19th century granary ladders from Burkina Faso and Mali, Vigango ancestor sculptures from Kenya, contemporary paintings from Ghana and Kenya: Ernie Wolfe Gallery, (310) 478-2960.

Crafts: Contemporary pieces from Ghana, https://www.novica.com .

Collection: Contemporary furniture and accessories from the National Geographic Home Collection:

Kuba cloth: From the Congo at Modern Tribal, Palm Springs: (760) 778-3896.

Artifacts: Ethiopian shields and Ebo tribal sculpture from Nigeria at Galeria, Palm Springs: (760) 323-4576.

Fine art: Benin bronzes, Senufo and Dogon figures, and Chokwe and Fang masks at Lacy Primitive and Fine Art, Los Angeles: (323) 653-1655.

Beaded headdresses: From Cameroon, at Pegaso International, Los Angeles: (310) 659-8159.