The post-granite age

- Share via

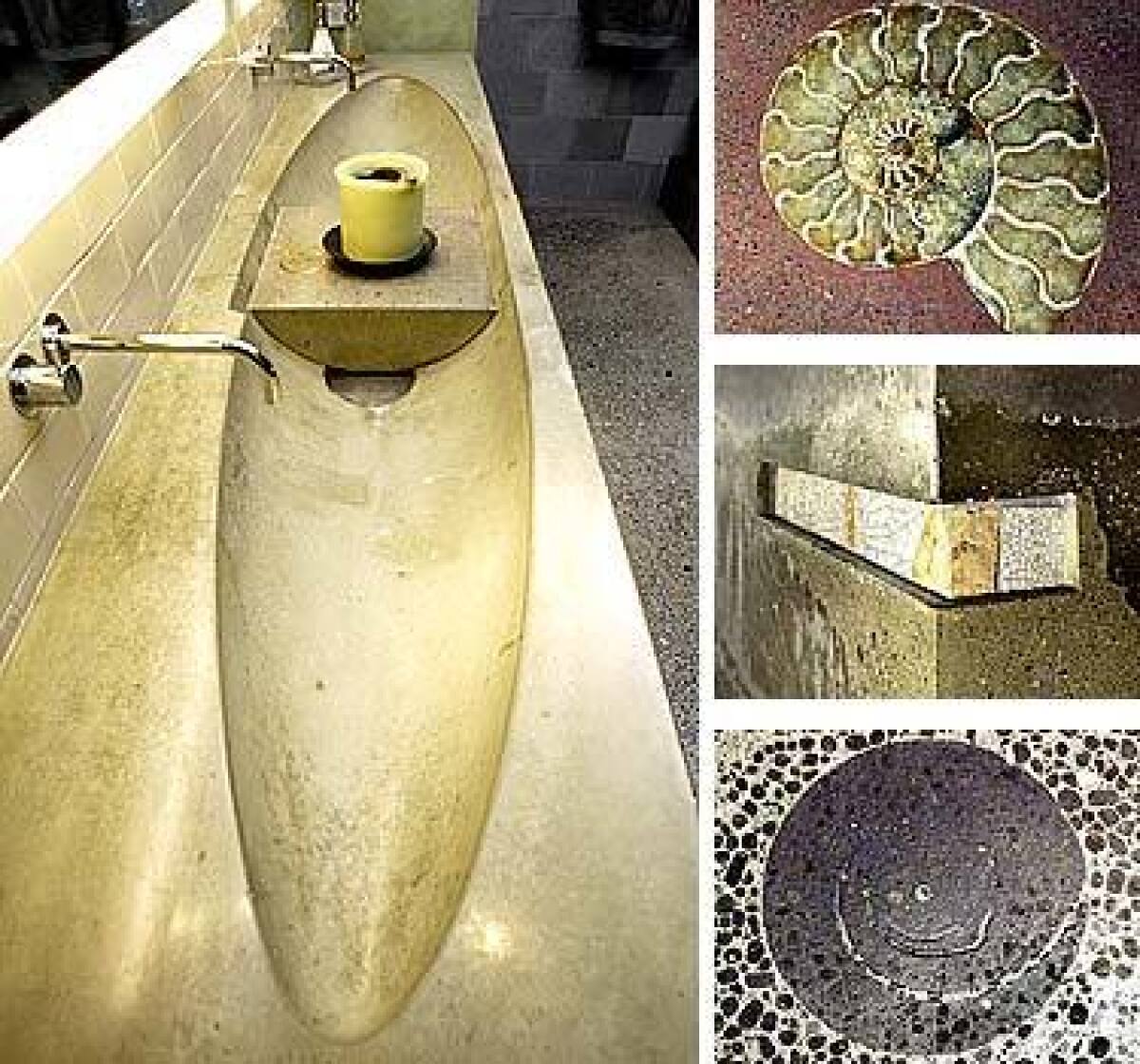

In Fu-Tung Cheng’s hands, a formerly cold, gray, rough material of little aesthetic charm is transformed into surfaces smooth enough to lay your cheek on, into lavender and rust and celadon-colored counters that dip and curve into sinks and basins, into a critical element of home design.

Concrete, the stuff of cinder blocks, sidewalks and freeway overpasses, is moving into high-end kitchens and bathrooms whose owners, like developer Wendy DeCenzo of San Francisco, are “way, way past granite.” On the leading edge of this innovation is Cheng, whom architect Will Bruder calls “the master of the craft of concrete on a residential scale, bar none. Nobody even comes close.”

Other artisans of concrete are finding an increasing demand for their work as well. In Venice, James DeWulf of DeWulf Concrete says, “Every time I complete a job, I get five more referrals. There’s something about concrete that draws you in. You just want to run your hand across it.”

Although granite has for decades reigned supreme in high-end kitchens, consumers looking to get creative are increasingly turning toward concrete. “Granite is going to continue to be popular, but people are looking for alternatives,” says San Francisco designer Joanne Cannell. “Concrete can produce a more unique look. All counters don’t have to be the same.”

In former AOL Chief Executive Barry Schuler’s Napa Valley kitchen, they’re not. He recently hired Cheng to design his entire kitchen. “I wanted it to be a piece of sculpture in and of itself,” says Schuler of the 500-square-foot room, built with concrete, stainless steel, bamboo, zinc, granite and cast polyurethane. “I smile every single day I’m in that kitchen, because it’s like you’re standing in a work of art.”

But concrete isn’t just for multimillionaires. Cheng has published a book and made an instructional video that walk everyday folks through the process of pouring their own countertops. He also manufactures NeoMix, a line of concrete mixtures and mix-ins.

Try this at home

Jeanine SMALLEY, 26, and her husband found “the ultimate fixer-upper” in Danville, Calif., last May and decided to build countertops themselves. After consulting Cheng’s book and video and using a healthy supply of NeoMix, they hammered together a mold in their garage, then mixed, poured, waited, polished and mounted.The process took nearly a month, and there were snags — such as when Smalley, her husband and her father added too much cement to the concrete mixer “and the powder was sliding everywhere,” she says. “Then we finally added enough water, and concrete just started flowing out, and I was trying to catch it with my hands.”

But despite being covered head to toe in concrete for weeks, Smalley would do it again if she had the chance. “I love the fact that this was a creation of our own,” she says. “There are some imperfections, but it’s OK. It looks fabulous.”

“It’s about making accidents happen, but keeping it so the glass won’t slough off,” Cheng says when he arrives, dressed in black slacks and a turtleneck. He poured the backsplash, he explains, covered it with glass, then drilled through until the bit hit the back of the mold, and bang! The glass shattered but the surface remained intact.

“To me, that’s what’s fun,” says Cheng. “The ultimate freedom is to respond in the moment to what’s going on . Now I have all these tools in my arsenal. I’m always looking for new ones.”

Accidents and serendipities have always informed Cheng’s design, his art. He rarely tosses things and starts over. He studies unintended results, learns how to replicate and control the processes that produced them. He admits a mistake to DeCenzo.

“I guess I should tell you this, because it’s in my next book,” Cheng says, smiling. He walks toward the focal point of the living room, the blue-gray wall and countertop striated with green that serves as an elevated hearth. A few minutes before, DeCenzo had praised this installation as an example of Cheng’s genius. Now she listens as the designer tells her about everything that went wrong.

The plan was to pump concrete up from the street and pour it into the form in place. Cheng told his workers to protect the form with plastic — any nicks or tears in the mold transfer to the concrete’s surface — but the wet concrete spewed from the hose so quickly and with such force that it pulled the plastic into the mixture, “sucked it in like a sea gull into a jet engine,” Cheng says. “They were desperately trying to pull it out of the concrete, but it tumbled inside and trapped air.”

The result was a disaster, a surface marred by deep gullies and covered in melted painter’s plastic.

Instead of tearing out the bad pour, Cheng studied its cratered surface. He used a blowtorch to burn out the plastic. Then he filled in the holes with rocks and green-tinted cement, and sanded and polished until the wall and countertop were smooth — hence the striations that turned a simple concrete surface into a piece of art. Ruin first, then salvation.

Echoes of his past

There is a history that’s ingrained in each Cheng design, that informs each accidental innovation. Rub your hands over the contours of any Cheng creation and, know it or not, you are invoking a Los Angeles evening in 1954 .It was already dark when the Cheng family climbed out of their Nash Rambler and carried empty rice sacks down to the Los Angeles River. Fu-Tung was only 7, but he clasped his flashlight and followed his mother and four older brothers onto the banks below, where they quietly filled the bags with sand and hauled them away. In the days following they collected thousands of smooth, round pebbles from Redondo Beach, and stockpiled the sand and pebbles at their farmhouse in the Valley. The Chengs were making concrete to pour themselves a driveway.

If Cheng could shout back to himself and his mother and brothers, standing outside in the midday sun mixing concrete in a wheelbarrow, he would explain that beach pebbles are too smooth and uniform to work effectively as aggregate, and that using more sand and pebbles and less cement powder isn’t the best way to cut cost.

Or maybe the memory is too sweet to interrupt. As Cheng writes in the acknowledgments to his first book, “Concrete Countertops” (2002), he will never forget “the sound that driveway made when we drove over it for the first time.” It sounded like crunching potato chips.

Cheng is not an architect, although he employs three, and what he knows of construction he mostly taught himself. It would be easy to assume that Cheng fell in love with concrete while tiptoeing toward the L.A. River with his brothers. But that is not the case. After pouring that ill-fated driveway, it would be years before Cheng would fool with concrete again.

“In tai chi, when you do sparring, you can’t ever have the notion that you’re going to take someone down,” says Cheng, sitting on a black couch in his Albany, Calif., living room. “It’s almost like an accident. Like you dropped some keys and you catch them.”

This modest Schindler-esque bungalow has been Cheng’s accidental laboratory for 34 years — it is the confluence of happenstance and hard work. No building material here is simply a material: Each concrete countertop, each polished floorboard, each inch of plaster is linked by memory to the circumstances that shaped it. As Cheng recalls the story of his house, he is also telling his story.

It was 1973 when he saw the flier at a local health food store: “Albany’s Finest Victoriana,” it read. “Squirrels, raccoons, a well. Death of my love makes it a drag to continue.” The price was $16,500 — about 16 times what Cheng had in the bank — but when you’re young and you have nothing, anything seems possible. He jotted down the address and hopped on his Vespa. What he saw was less a house, he remembers, than a ramshackle heap. He turned and putt-putted away, but in a second the screen door flew open and the 50-year-old owner chased Cheng down the street.

Five minutes of convincing, and Cheng was taking the tour. “It was terrible,” he remembers. “There were rats. I tried not to touch anything.” Some rooms had dirt floors — the owner had torn out rotting boards and hadn’t replaced them. The kitchen floor seemed straight out of a carnival house: dozens of mismatched slabs of particleboard had been cobbled together, and the effect was “like walking on some rocky surface,” Cheng says.

A week later Cheng decided it was too good a deal to pass up. He borrowed the down payment from his businessman brother — the only brother who isn’t an artist. And two years after graduating from UC Berkeley with a degree in fine art, Cheng began to remodel. He knew the smart move would be to tear the wreck down and start anew. But he had no money, no job. “It was going to be my house,” Cheng says. “So I started working on it.”

The dirt floors and uneven kitchen would have to wait. He was inspired by a Greene & Greene house on the Berkeley campus — “I loved the way they did the roof beams,” Cheng remembers. So he spent his last dollar on the front roof eaves and a new redwood gutter.

For money, Cheng became, an expert at modifying and repairing Vespas. “Then I’d reel home at about 1 o’clock,” Cheng remembers, “take a nap and start working on the house at about 2:30.” He would work until dark. He kept to this routine for the next 10 years.

To learn new building techniques, Cheng wandered onto construction sites and asked if he could watch. For materials, he would scour the local salvage yards and offer to haul away scraps from demolition sites. When the city of Berkeley tore down Willard Junior High School, the gymnasium floorboards became his living room floor. When the Navy abandoned Treasure Island, Cheng salvaged lumber from military bungalows and used it to rebuild the rear of his house.

Learning by doing

Cheng grew confident enough to hang a sign in the local tai chi studio advertising his skills in “carpentry, plumbing and electrical.” Before he had the chance to redo his own kitchen — for the time being, he covered the floor with Astroturf — a cousin hired Cheng to design his kitchen. “What seduced them was my drawing,” says Cheng. “But once I had the drawing, then I had to build it.” Next, Cheng used his sketches to win over a Berkeley professor. And it was in designing this kitchen that Cheng again encountered concrete.“We did a sink and had to go through a long, elaborate process to waterproof it,” Cheng remembers. “That was the first time I realized that maybe I could do something with concrete.” For the next sink he designed, Cheng built a mold, mixed and poured concrete, waited for it to dry. He planned to tile the sink, but the shape he pulled from the mold was smooth and beautiful in its own right. Cheng was hooked; he began to experiment with concrete by adding fiber for strength and pigment for color, by changing the ratio of ingredients to create distinctive effects, by hammering together elaborate molds.

Cheng’s early work in concrete coincided with Santa Monica architect David Hertz’s development of a lightweight concrete called Syndecrete, and the two are friends . Hertz’s work has an environmentally sensitive point of view. “I wasn’t happy with the existing choices, petrochemical plastics or ceramics and polished stones,” Hertz said.

Cheng Design (www.cheng design.com) now employs 20 designers, architects, fabricators, marketers and crew. Once known mostly for kitchen countertops, Cheng is increasingly asked to carry over his unique materials and design sense to whole interiors and exteriors. He has designed dozens of bathrooms and kitchens nationwide — and six entire houses. He hates being typecast as the “king of countertops” — he wants to be known for his larger projects as well — but he will admit that the anti-granite movement has been good for him.

When author Terry McMillan burst into his studio in 1994 and told him, “If I have to see any more granite, I think I’m going to puke,” Cheng drove her to his Albany house. There, in the 21-year-old kitchen of a once-ramshackle heap, he showed her a stainless steel sink ensconced in gorgeous gray-green concrete, raised copper strips inlaid to protect the countertops from hot pots and pans, an ammonite fossil — Cheng’s signature inlay — and a custom hood, covered in what looks like engraved plaster.

“If I had found Fu-Tung earlier, he would’ve designed my whole house,” says McMillan. As it is, he designed her kitchen, bathrooms and fireplaces, and the walkway around her pool. Oh yes, and her driveway. This one doesn’t have the sound effects, but like everything Cheng builds, it has the history.

*

Steven Barrie-Anthony can be reached at steven.barrieanthony@latimes.com

*

(Begin Text of Infobox)

Staying local for concrete ideas

James DeWULF of DeWulf Concrete in Venice (www.dwconcrete.com) offers 30 standard hand-mixed colors and specializes in a “cream finish,” in which the concrete is floated and smoothed so the sand and aggregate sink to the bottom and the smoother cement rises to the top.

Most of his projects are residential. Kitchen countertops, which he often casts with built-in sinks for a seamless finish, are “the largest chunk of my business,” he says.

He’s done projects for decorators Kenneth Brown, Susan Cohen and Joe Nye, and his work has been shown on HGTV and the BBC.

Why concrete? “It has imperfections and does its own thing. People are bored with the look of granite and with Corian, which is an intelligent surface but just isn’t sexy,” DeWulf says.

Architect David Hertz of Santa Monica developed Syndecrete, a lightweight concrete formulation, for his architecture firm, Syndesis Inc. (www.syndesisinc.com). He has custom-blended concrete in more than 600 colors for commercial spaces including the Sony Metreon in San Francisco and Nike’s Goddess stores. Hertz was the primary architect for a house for actress Julia Louis-Dreyfus, and he designed concrete work for actor Tim Allen’s home. In 2004, Hertz’s work was featured in two museum shows.

“Although it is man-made,” Hertz says, “concrete consists of all natural materials and has a humble quality. Because it can be customized, concrete restores the notion of craft.”

*

— Adamo DiGregorio