At the Museum of Death, every day is like a Charles Manson anniversary

- Share via

There are morgue photos of the Black Dahlia, aka Elizabeth Short, the lower half of her body separated from the upper by a foot or so of empty air. Two toddler-size white caskets. Serial killer John Wayne Gacy’s “authentic clown shoes.” A suicide suit and Nikes taken from the body of a Heaven’s Gate cult member who died along with 38 others. The shrunken heads of half a dozen men — well, as far as anyone can tell, they’re men.

But here at the Museum of Death, Hollywood, you won’t see special preparations for the golden anniversary of the Tate-LaBianca murders, carried out half a century ago this month by Charles Manson’s notorious “family.”

Because JD Healy, museum co-founder, does not believe in “exploitation,” he insists. “Do you know how sensational I could be if I wanted to be? … That’s not why we’re here.”

In case you’re wondering why the museum is here on Hollywood Boulevard near Gower Street — and in New Orleans’ French Quarter and soon to be in Seattle’s Pioneer Square — Healy has a sober-sided answer: to make our death-averse culture think about our collective destination.

Manson and his cruel clan already have a place of honor in the 3,000-square-foot collection, where they claim more prominent real estate than nearly any other deathly display.

In fact, now that it’s the anniversary, one thing is clear: Interest in Manson isn’t heightened, because it’s never really gone away. Just ask Eric Holler, who sells murderous memorabilia on serialkillersink.net and said he supplied the museum’s New Orleans branch with a set of original Ted Bundy courtroom sketches.

“I’ve been doing this for 25 years,” Holler said. “Manson has been the top seller for 25 years. It doesn’t matter — anniversaries, the [Quentin] Tarantino movie. … I don’t see an uptick. There’s always extreme interest.”

Extreme enough that another murderabilia site, supernaught.com, is asking $50,000 for a set of Manson’s prison dentures, letter of authenticity included. If that’s out of your price range, you can get a pair of Manson’s prison boxer shorts for $3,500, or the remaining half of a burrito that the Svengali of Spahn Ranch nibbled on during a 2002 visit. That one goes for the bargain price of $1,250.

In his 2014 book “Why We Love Serial Killers,” author Scott Bonn said some believe “items once held by the likes of Bundy or Gacy are endowed with magical powers,” and the owners of such objects — be they museums or private collectors — can tap into that supernatural force. It’s called the “talisman effect.”

Stephen Kay has a much less fanciful theory about the allure of the homicidal. Particularly about Manson and the family, whom the retired prosecutor helped put behind bars and keep there through 60 parole hearings at which he argued for various members’ continued incarceration.

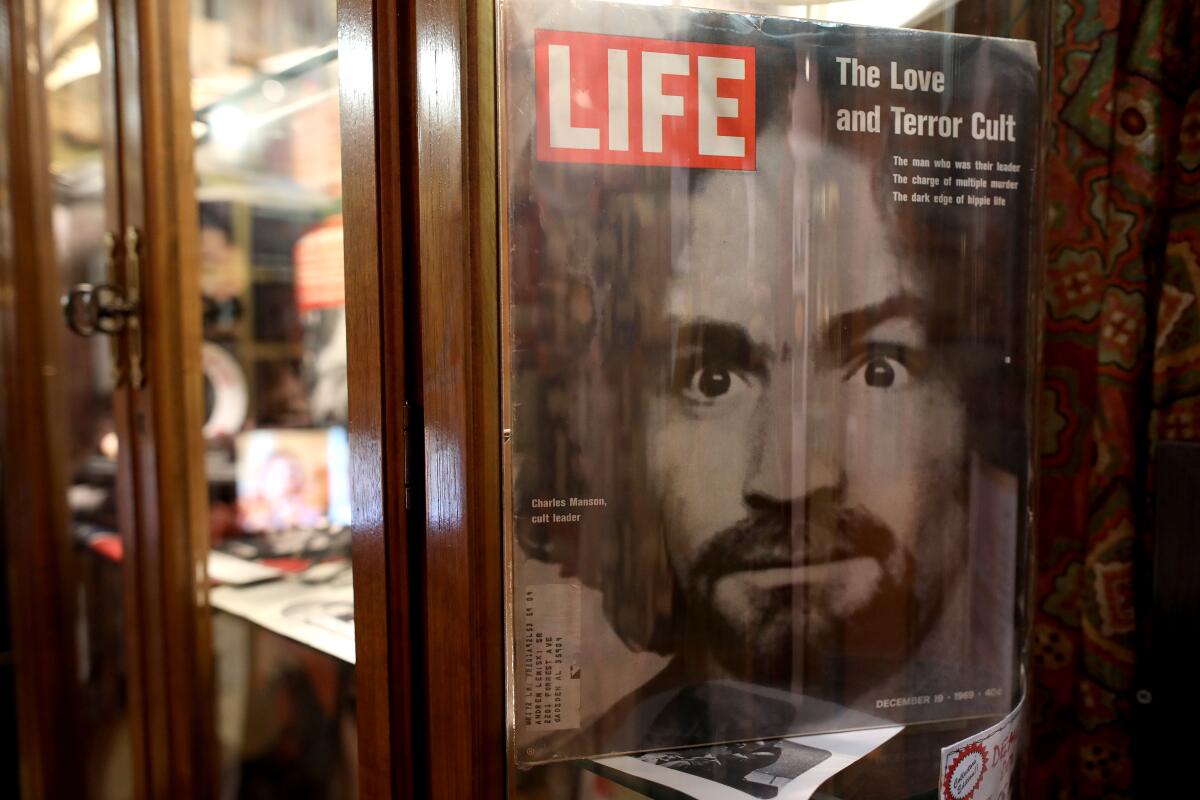

People in the United States, Kay said, like to be scared. And when Life magazine featured a wild-eyed Manson on its Dec. 19, 1969, cover — an image that is famous to this day — U.S. audiences were handed their perfect boogeyman.

“People in the United States, and I don’t count myself as one of them, seem to like horror pictures,” Kay said. “Well, here the people had a real-life monster on the cover of Life magazine. Here was this monster who could convince young people to commit murder for him.”

Healy is even more matter-of-fact about the Museum of Death, its soon-to-be-two outposts and the bulging archive that holds the collection’s overflow: “I’m interested in weird objects.”

Which is abundantly clear when walking past the 12-foot-or-so skull mural that adorns the museum entrance, plunking down $17 and stepping inside.

One of the first rooms visitors encounter displays antiques and artifacts of the funeral and mortuary trades. There’s a wicker casket, a style museum manager Erek Obrist says came to prominence during the Civil War, when bodies were shipped home by train. It is lined with tin and could be packed with ice for replenishing at each depot.

There’s a vast collection of funeral home fans and calendars and salad tongs and spoons. A video that shows how to embalm a body plays in a continuous loop.

“A lot of people have never seen or know the details that go into an embalming or an autopsy process,” Obrist says before a class of nursing students files in. “It’s fascinating. It’s science, really, that’s what it boils down to.”

There’s a taxidermy room and a suicide hall and the “cannibalism niche.” On a big screen in the Theater of Death, Thomas Noguchi, coroner to the stars, performs an autopsy. His blue rubber gloves, slick with blood, are stark against the open body cavity. Nobody famous, in case you were wondering.

“A complete autopsy in 45 minutes,” says an admiring Obrist. “Like a sushi chef. Zip, zip, zip and it’s done.”

Beneath the screen stands Chaos, co-founder Cathee Shultz’s beloved pot-bellied pig, glass-eyed and standing at eternal attention. Buddy, Shultz and Healy’s recently departed beagle, just came back from the taxidermist and soon will take his place in the pantheon of preserved pets.

The Death of Elvis Bathroom is papered with stories of the King’s demise.

And then, there’s the California Death Room. Half is taken up with the O.J. Simpson case, the Black Dahlia and other, lesser-known crimes. The rest is all Tate-LaBianca.

What Obrist calls “Manson’s personal blankie” takes up much of one wall. On first blush it’s just a well-worn quilt, painstakingly sewn by “Manson’s girls” while the family resided at Spahn Ranch. On closer look, the pattern becomes evident: the perky flowers and cheerful ginghams, paisleys and butterflies have been lovingly stitched into 36 swastikas.

A glass display case holds signed baseballs, one bearing Manson’s signature, the other, chief prosecutor Vincent T. Bugliosi’s. There’s a Charles Manson ventriloquist dummy (“one of three in existence,” its label reads) and two odd little dolls, a black scorpion and a red spider. Manson made them using thread and elastic unraveled from his prison-issue underwear and dyed them with Kool-Aid.

But the most troubling items in the Manson room are the crime-scene photos taken after family members murdered three women and four men on a two-day rampage in August, 1969: Sharon Tate, Abigail Folger, Voytek Frykowski, Steven Parent, Jay Sebring, Rosemary and Leno LaBianca.

The photographs show a sprawled corpse and others peppered with knife wounds. A stout white rope flung over a living room beam with Tate tied around the neck on one end, Sebring on the other. And blood. So much blood.

“The crime scene photos are,” Obrist begins. Then he pauses for what feels like a long time. “Very intense. They’re uncensored. And usually when people see them, it is for the first time. And they are taken aback.”

By the brutality of the murders, how vicious and senseless they were. No podcast can do them justice, he says, no book, no movie can show what the Manson family rampage truly entailed.

“Seeing the photos,” Obrist says, “there’s no shadow of a doubt. You can’t sugar-coat the photos.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.