Prison hunger strikes in the U.S. are few, and rarely successful

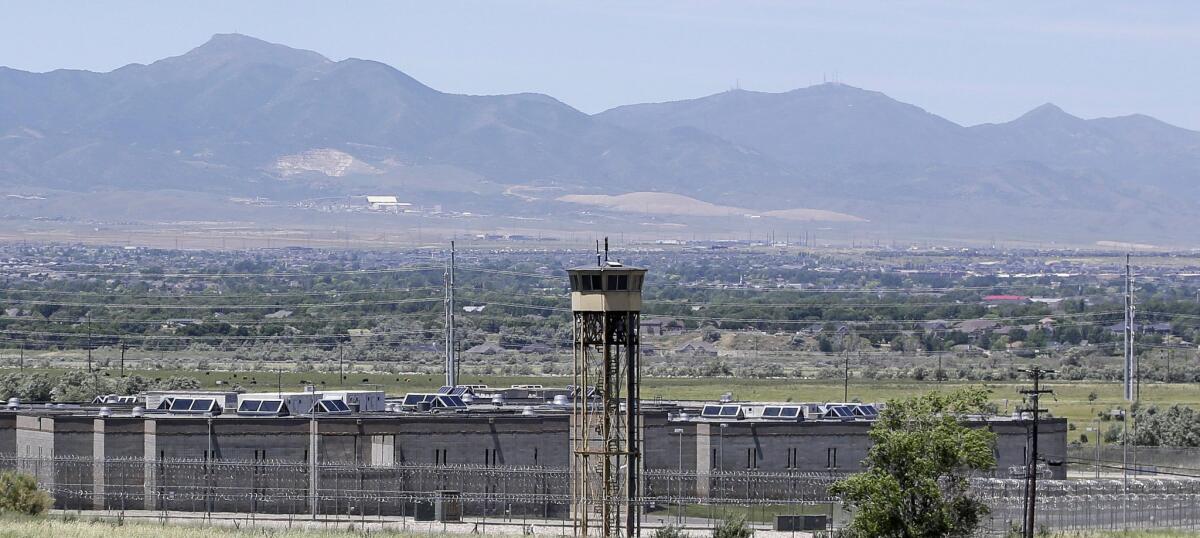

Inmates at Utah State Prison in Draper staged a hunger strike to protest living conditions in the maximum-security facility.

- Share via

For inmates in Utah State Prison’s highest-security units, life is lived almost exclusively within their cell walls.

The maximum-security prisoners, some of whom have been there for decades, live in near-isolation, locked in small cells with a cellmate and allowed out for only one hour every two days. Even then, they are limited to interactions with their cellmates, activists say.

Prisoners who are part of the Security Threat Group are placed in the most restrictive units for a variety of reasons, including behavior and personal safety issues. Prison administrators often say isolating certain prisoners is necessary to thwart violence and gang activity.

The prisoners don’t have access to rehabilitative programs or educational opportunities, according to the American Civil Liberties Union’s Utah chapter, and are not allowed to work. Some inmates have described spending years at a time under such restrictions.

Last week, 42 inmates at the maximum-security facility in Draper, Utah, declared a hunger strike in an attempt to improve their living conditions, activists say.

The prisoners, who officials say are all documented gang members, had been refusing meals since July 31, but on Wednesday morning officials said all but 11 of them accepted breakfast trays. By Wednesday evening, officials said, all but two had agreed to stop striking. There was no indication as to whether prison officials had agreed to any of the six demands listed by the strikers.

Prison doctors are monitoring the inmates who are continuing their hunger strike.

Administrators say that among the demands listed by prisoners is the relocation of gang leaders from the maximum-security portion of the prison. Prison officials said that as they began meeting with individual inmates to discuss the strike on Tuesday, several inmates covered their cell-door windows with paper and broke sprinklers in their cells, leading to flooding. Officials said some of the inmates were denied privileges like TV access and commissary purchases as a “standard consequence” for inmates on a hunger strike.

About 160 prisoners live in the Uinta 2 maximum-security unit where the hunger strike is occurring. The prison has five maximum-security units in the Uinta facility altogether. The ACLU of Utah says it supports the inmates’ strike and has urged state officials to improve conditions for the prisoners quickly.

Demonstrations like theirs are unusual but, as Wednesday’s dwindling count shows, victories for strikers have been few and far between.

“It’s one of the few ways that prisoners can draw attention to themselves and their plight. … It’s obviously an act of desperation,” said Martin Horn, a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice at the City University of New York and a former commissioner of New York City Corrections.

Some examples of past efforts include the more than 100 detainees involved in a hunger strike at the U.S. military prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, with dozens being force-fed via tubes. The military stopped releasing numbers on hunger strikers at Guantanamo in 2013. At the time, there were 15 reported participants, all of whom were being force-fed.

In the U.S., hundreds of inmates at a federal immigration detention center refused meals in April 2014; by the fifth day, the numbers had dwindled to five detainees.

In 2012, more than 40 prisoners at the Red Onion State Prison in Virginia, a super-maximum facility, declared a hunger strike, saying changes to isolation policies weren’t coming quickly enough. A week later, officials said all had returned to eating without the prison addressing their demands, though some strike supporters cast doubts on the prison’s version of events.

In March, about 40 inmates began a hunger strike at Ohio’s highest-security prison in Youngstown to protest increased restrictions on recreation, education and religious gatherings, according to an Associated Press report. By the five-week mark, all but one of the prisoners began eating after officials said they would review the restrictions.

Some California inmates have had some success following mass hunger protests, though officials say many policy changes were underway before the protests.

In the summer of 2013, more than 30,000 inmates participated in a mass hunger strike in 22 California state prisons, demanding changes to policies that left maximum-security inmates in isolation indefinitely, some for decades. The protest was the largest of its kind in recent years and lasted two months.

It ended after state lawmakers promised public hearings on prison conditions and the use of solitary confinement.

“One of the reasons we may be seeing this in Utah is because [the inmates] perceive that the effort in California did have some effects,” Horn told The Times in an interview Tuesday.

The 2013 hunger strike, and a series of others by prisoners in 2011, helped bring substantial changes in solitary confinement, says Ann Weills, an Oakland-based attorney representing inmates in Northern California’s Pelican Bay State Prison who are suing state officials over conditions there.

“When we started litigation in 2012, there was no way out of the [Security Housing Unit] except if you snitched” or renounced a gang, Weills said. “Without the strikes … we would not be where we are today in making the changes we have at Pelican Bay.”

Prisoners there have been granted basic quality-of-life improvements, Weills says, such as being allowed to have wall calendars in their cells and being allowed to use exercise balls and other equipment during recreation time, which is often an hour or less per day. They’ve been allowed to have their photographs taken once a year to send to family members they haven’t seen in years.

Perhaps most significantly, prison officials also changed how they decide who gets housed in the security housing unit and created a “step-down” program that lets inmates eventually leave the unit.

But, Horn believes, state corrections officials are loath to say changes are the result of any hunger strike for fear it could encourage such protests.

The Utah Department of Corrections said in a statement Monday evening that it “does not capitulate to demands” but was continuing to review policy changes related to how inmates are selected for the restrictive units, educational programming and the time prisoners spend outside their cells.

Times staff writer Paige St. John contributed to this report.

For more breaking news, follow me @cmaiduc

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.