Unearthing a Hidden Jewel in Tuscany

- Share via

PISTOIA, Italy — The guidebook had let us down badly in the choice of a hotel at Lake Garda, and now we were heading south to Pistóia in Tuscany and certain doom. The next hotel on our itinerary had come from the same wretched book.

“This place we’re going to is so bad,” I joked to my wife, Jennifer, “that the Italian government has tried to house refugees in it and they refuse to go.”

The decision to visit this less traveled part of Tuscany had been a gamble in more ways than one. On our mid-May trip, we could have gone to Chianti country, with its incomparable hills, imposing villas and cedars standing like sentinels over endless stretches of vineyard. We could have gone to the more popular cities of Florence, Siena, San Gimignano, Lucca or Pisa. But we decided to forgo known pleasures for a Tuscany untouched by hordes of tourists. Another guidebook--a cultural guide--had suggested that Pistóia, 21 miles northwest of Florence, was not without its charms. So we were headed into the unknown and, to make matters more unnerving, we had persuaded two friends, Paul and Mimi Horne, to join us at the Villa Vannini, the country house hotel recommended in the first guidebook.

Fortunately, even bad guidebooks can sometimes redeem their worst mistakes, and the best ones prove their worth. In Pistóia and Villa Vannini, our luck turned.

The Villa Vannini is perched on an Apennine hilltop, 1,000 feet up and four miles north of Pistóia, and our first sight of it was reassuring. Built in 1780 and used as a summer residence of nobility from Florence and Pistóia during the 18th and 19th centuries, it is a three-story hostelry with only eight bedrooms, all tastefully furnished with antiques. A large terrace on one side of the building is surrounded by linden trees and oaks, and just beyond, dominating the landscape, stands a magnificent deodar, a Himalayan cedar.

The bedrooms are simple and lack the features that many travelers take for granted. There are no telephones in the rooms, no TV sets, no radios. Each room has its own bath, but only two are attached; the rest are across a corridor. There is no elevator to the upper floors and no air-conditioning. The villa is clean and comfortable, but not a place that spoils with little luxuries in the bedrooms.

What makes the Villa Vannini exceptional is its restaurant, the Deodora, named for the cedar. Luigi and Marta Bordonaro, a friendly couple from Pisa, manage the villa for its elderly owner, Maria Rosa Vannini. Luigi is not simply an excellent self-taught chef; he is a culinary maestro, a magician who gives traditional Tuscan dishes a modern and innovative touch that is consistently outstanding. Marta makes the dough for the pastas, bread and desserts, and they match the quality of Luigi’s cooking. All four in our party have had years of experience in Italy, and we unanimously agreed we had never dined as well.

Each dinner consists of four courses, so well balanced that you never get up from the table feeling you have eaten too much. A typical menu: chicken terrine with a small salad of marinated onions; pappardelle (extra-wide noodles) with zucchini flowers; Cinta Senese, a small, richly flavored pig native to the Siena region, braised in Chianti with sage-flavored mashed potatoes; and Marta’s crema caramellata with a prune on top, which was a cross between a crème caramel and a crème brûlée--and superior to both.

On the night after this meal, the second course was unusual: ravioli of Cinta Senese placed in the fold of a cloth napkin. Luigi believes that sauces served with ravioli detract from the flavor of their meat, so he serves them in a napkin to preserve moistness and heat. Delicious. Another of my favorites was pappardelle with rabbit, duck and cockerel.

The Bordonaros stock only Tuscan wines, most in the $20 range but some double that or more. The modestly priced wines were uniformly good so we stayed with them, mainly Rosso di Montalcino Brunelli 2000 and Nobile di Montepulciano Salcheto 1998 or 2000. For our one fish dinner (six different fish or shellfish in four courses), Marta chose for us one of the few good Tuscan whites, I Sistri Chardonnay Felsina 1999.

We approached the Deodora with a measure of skepticism, committed to having only one meal there. Within reasonable driving distance, there are at least four Michelin one-star restaurants. But after our first night at the Deodora, there was never any question of where we would eat the rest of our dinners. With one exception.

Before coming to Villa Vannini, the Bordonaros ran a restaurant called La Volpe e l’Uva (the Fox and the Grape) in the mountain village of Buti, between Pistóia and Pisa. It’s now in the hands of their daughters, Francesca and Chiara, and it has won rave reviews in several Italian publications, and even one in Japan. Luigi taught Francesca and claims she is now a better cook than he. So at his insistence, we dined at La Volpe one night. We agreed Francesca is a superb cook, but her menu lacked the delicate balance found at the Deodora. Still, La Volpe is worth a detour.

Pistóia is an excellent base for visiting Lucca, 30 miles to the west, Pisa, 15 more miles beyond, and Florence. Also within striking distance are two villas built by Florence’s ruling Renaissance family, the Medicis. At the village of Póggio a Caiano, halfway along the road to Florence, is a villa that was built for Lorenzo the Magnificent by Giuliano da Sangallo in the 15th century and decorated under the guidance of Lorenzo’s son, Pope Leo X. Near Carmignano, south of Pistóia, is the Medici Villa di Artimino, built by Bernardo Buontalenti in 1594 for Ferdinand I, Grand Duke of Tuscany at the time. Although the villas are open to tours, we didn’t visit them, instead heading for Pistóia.

The approach to Pistóia is anything but inviting. Pistóia and nearby Prato are the heart of Europe’s largest plant nursery development, and buyers from all over the world come to this town of 90,000, which, at first glance, appears to consist only of drab modern buildings. But once you penetrate the medieval town center, that perception changes. A local guidebook proclaims defensively but appositely that Pistóia is an “unknown jewel.”

Living in the shadow of Florence, Pistóia never had any possibility of rivaling that great center of art, Renaissance culture and power politics. But in the Middle Ages, when the town was caught up in the struggle between the Guelphs (the party of the pope) and the Ghibellines (the aristocrats who supported the German emperors), Pistóia was a prosperous little town. Its wealth was swelled by pilgrims who came to pay homage to a relic of St. Jacopo, brought from Spanish Galicia in 1144.

Originally a 3rd century BC Roman settlement, Pistóia was conquered by the Lombards in the late 6th century, then became part of the Carolingian Empire in the 9th century. In 1351 it lost its independence to Florence.

Today, you can easily imagine what a lively place it was in the Middle Ages--with artists and architects pouring into it from Pisa, Florence and Siena to adorn it with those unknown jewels that distinguish it today, wealthy families busily weaving Machiavellian plots, ordinary citizens manning the ramparts against neighboring enemies. Few of the artists who came here achieved lasting fame, but what they left behind is remarkable.

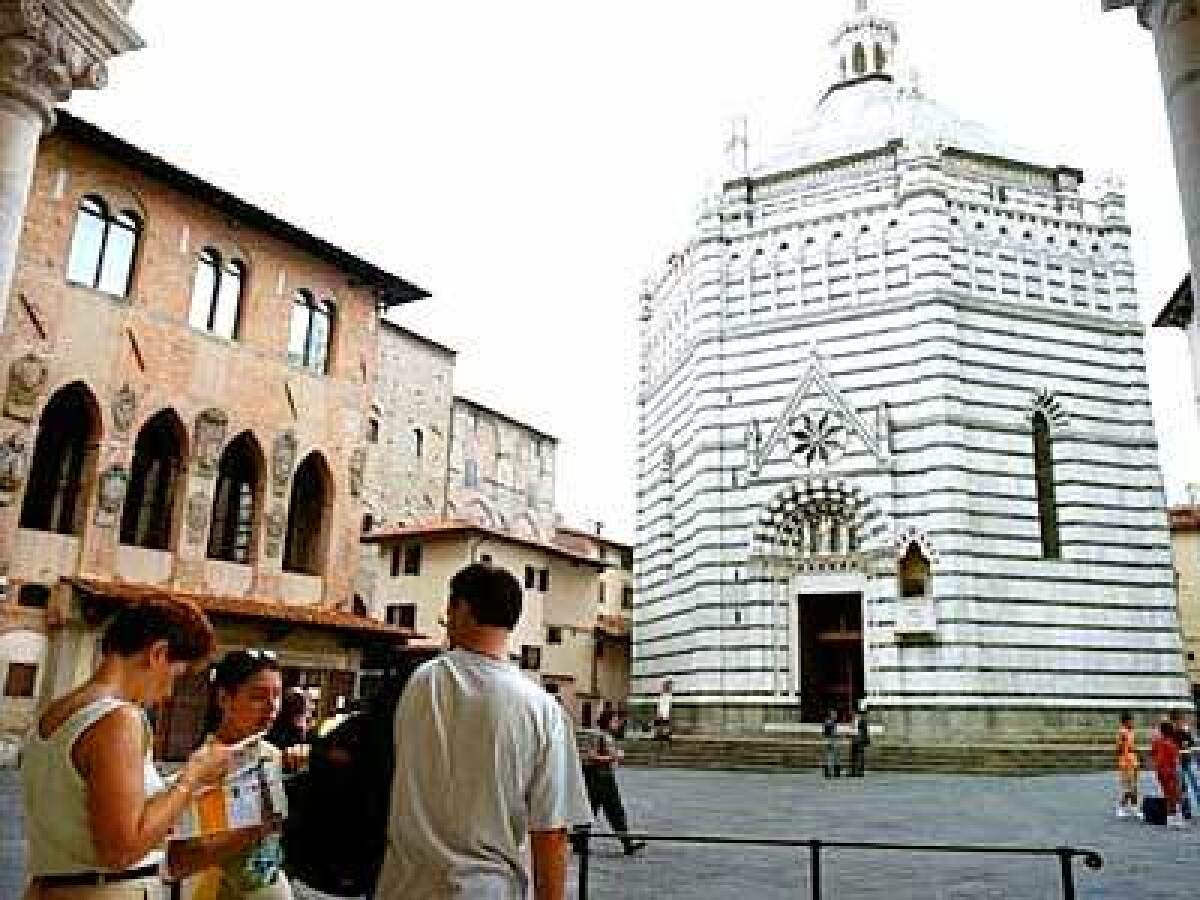

The most striking of the Pistóian jewels are the 12th century cathedral of St. Zeno, built in a Pisan Romanesque style that was handsomely restored in 1999; its 220-foot bell tower; and its stunning octagonal Gothic baptistery. These form the principal components of one of the finest piazzas in Italy, complemented at opposite ends by the 14th century law courts, once the governor’s palace, and the 13th century town hall, which houses a civic museum featuring outstanding Florentine and Sienese works of art from the 14th to 16th centuries.

The 14th century Baptistery of St. John, like parts of the cathedral and bell tower, consists of alternating layers of white and green marble, reminiscent of the cathedral in Siena. It was designed by Andrea Pisano, a member of a Pisan artistic family that left its imprint on monuments throughout Pistóia.

A lunette in the portico of the cathedral holds a terra cotta of the “Madonna and Child,” by Andrea Della Robbia, and the coffered tunnel vault of the church is also decorated with his work. But the pride of the cathedral is a silver altar, mentioned in Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” which features 628 small figures designed by various artists over several centuries.

Behind the cathedral square is the Piazza della Sala, whose outdoor food market bustles with vendors and shoppers gathered around bountiful displays of fresh fruits and vegetables. (But a word of caution: Stay out of Pistóia on Saturdays, when the cathedral square and many nearby streets are taken over by a tacky outdoor clothing market.)

Go out the opposite end of the cathedral square from Piazza della Sala and you will descend along medieval streets to one of Pistóia’s unexpected pleasures: the 15th century Ospedale del Ceppo (Hospital of the Tree Stump), named for the stump in which alms were once collected. The Florentine-style portico is decorated with a series of colorful glazed terra cottas from the Della Robbia school, portraying familiar scenes of medieval life and death. Scattered throughout the town, all within walking distance, are splendid old palazzi, once the homes of powerful Pistóia families, and churches dating from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. After the cathedral, most prominent is the small Church of Sant’Andrea (St. Andrew), which also has a green and white marble Pisan facade. The elaborately carved marble pulpit, supported by six red porphyry columns resting on the backs of lions, is one of the masterpieces of Giovanni Pisano. The artist’s two original lecterns of the pulpit are now scattered--one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the other at the Museum Dahlem in Berlin.

My favorite among the churches is St. John Fuorcivitas, another Romanesque building in white and green marble. Although the church is in the heart of Pistóia, the word fuorcivitas indicates it was built outside the now-vanished medieval walls. Its exterior design is perhaps the most handsome in town. Inside, its main adornment is a “Visitation” by Luca Della Robbia, depicting a meeting between the Virgin Mary and St. Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist.

Also worth visiting is the 15th century Basilica of the Madonna dell’Umilta, Pistóia’s principal church in Renaissance style. Its massive dome, designed by Giorgio Vasari and clearly inspired by Filippo Brunelleschi’s dome for the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, is the third largest in Italy.

Pistóia will, of course, never compete with the great towns and cities of Tuscany. But that is one of its virtues. When we were there, there were no tour buses, no guides leading battalion-size groups through the streets. Just a few tourists, quietly relishing the pleasures of a town out of the Middle Ages that never managed to achieve the greatness of its neighbors, yet in its time of glory created a legacy of enduring beauty.

Ray Moseley, formerly a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, lived for five years in Italy.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.