Why didn’t this California snake cross the road?

- Share via

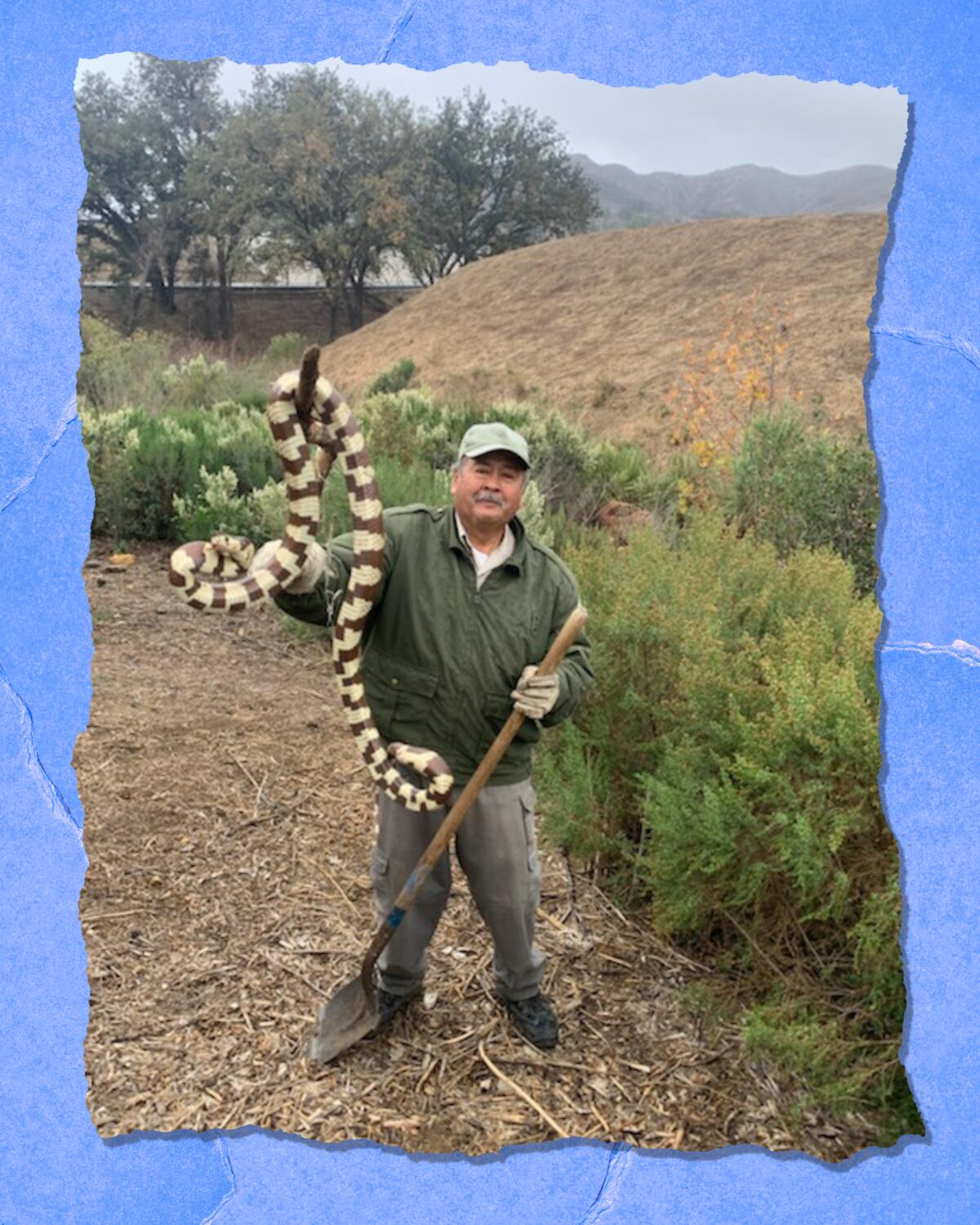

Snakes creep some people out. Not Alberto Silva, who tends native plant restoration areas for the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority in Southern California. While working near Liberty Canyon in Agoura Hills, he saw a native California kingsnake heading toward a busy road — and took swift action to move it to safety.

I love this photo for a number of reasons.

First, it shows the importance of having compassion for all animals, particularly those whose habitats have become fragmented. I shared the photo with snake expert Greg Pauly at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. “I’m quite familiar with this photo,” he wrote in an email. “It’s great that Mr. Silva kept the snake from moving onto a busy road. Just imagine how much better off our local snake populations would be if everyone shared his stewardship for wildlife. We see that as habitats get increasingly urbanized and fragmented that snakes with larger home ranges start disappearing. Because they are moving in search of food, mates, and safe spots to overwinter, snakes come across unfriendly people as well as roads. Over time, these populations decrease and eventually blink out because of the high levels of mortality.”

Second, the photo underscores the need for the planned Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing not far from where Silva rescued the snake. “The purpose of the project is to provide a safe and sustainable passage for wildlife across [the 101 Freeway] near Liberty Canyon Road in the city of Agoura Hills that reduces wildlife death and allows for the movement of animals and the exchange of genetic material,” the MRCA wrote when it posted Silva’s photo on Instagram.

And last, it made me think about California kingsnakes, a.k.a. Lampropeltis getula californiae. It’s a species I know little about, though I have seen some on the trail. They are mostly harmless and are described by those who keep them as pets as being docile. The L.A. Zoo website says kingsnakes eat other snakes, even rattlesnakes, noting they are “highly resistant to rattlesnake venom.” The largest population of California kingsnakes is found here in Southern California. They can be 2 feet to 5 feet long, according to the zoo. Though the one in the photo looks much bigger, it may be the angle of the camera that makes it look that way. The snake was not measured before it was released.

3 things to do this week

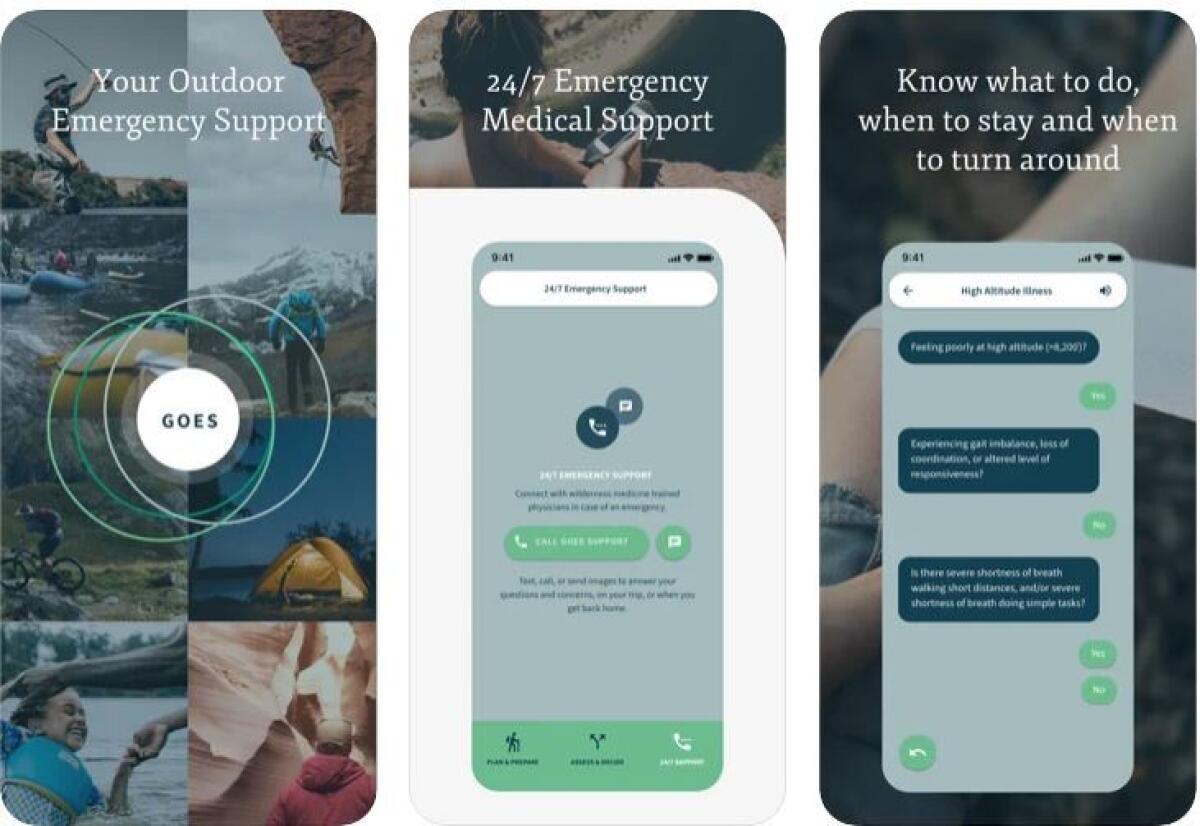

1. Try this back-country emergency safety app — on us. Readers of the L.A. Times and The Wild can sample a new app that puts wilderness medicine information and experts at your fingertips — for free. Global Outdoor Emergency Support, or the GOES Health app, is offering free, six-month subscriptions exclusively for our readers. Here’s how it works: Access trip planning and emergency safety advice whether you’re online or offline (you can use it in the backcountry even if you don’t have a cell signal) and call or text emergency-medicine doctors 24/7 when you have service, no matter where you are in the world. Download the app and enter the voucher code LATimesBenefit for the free subscription.

Dr. Grant Lipman, an emergency-medicine physician and former director of the Wilderness Medicine Fellowship at Stanford University’s School of Medicine, designed the app based on his decades of experience training others as well as serving as an expedition doctor and medical director for ultra marathons. I talked with him about the app and how it could help you in an emergency (edited for length and clarity).

Why did you create the GOES app?

Over the last 20 years, running the wilderness medicine program at Stanford, I was inundated by calls and emergencies around the world, people asking, “What do I do?” Really, it was the pandemic that made me appreciate that more people than ever are going outside. We’ve seen national parks explode. ... We really want people to get out there and enjoy the outdoors safely.

Tell me about the trip-planning and safety information.

When we were setting this up, we spent 100-plus hours with outdoors users from five different countries. We really appreciate that people are looking to the outdoors for a specific activity. It’s oriented to the user, what their activity is and what the environment is: Will it be hot? Will it be cold? High altitude or low altitude? [These things] dictate what illness they may encounter. ... People are really excited — spending their time and energy buying new hiking boots, and their Dri-Fit T-shirts and getting all their gels — a time when they are gathering information, so we put it all in one place.

That information is available offline. Why was that important?

We realized very quickly that most people won’t have satellite phones. Right now, once you’re offline, everything is available on the GOES app. You have access to clinical-grade algorithms that [can help] if you’re in distress or trouble. Two questions always come up: What do I do? And, to a lesser extent, Can I keep going, or do I need to end my trip and go home? The second one is a really hard question. If you’re through-hiking the John Muir Trail, you’ve trained for this, put your vacation on hold. ... There’s a lot riding on continuing this adventure. And I don’t take that lightly, but it’s always safety first. The questions on the app direct you to emergency treatments, whether you need to get help or whether you’re OK to continue.

If I’m in trouble, when should I contact GOES’ doctors?

Having been trained in wilderness medicine and trained a generation of experts, there is no compilation of anyone in the world answering an advice line like we’ve put together at GOES. We have 25 emergency-medicine physicians, trained in wilderness medicine, available by text and phone 24 hours a day. [They answer questions like:] I’ve been bit by a snake what do I do? I have a hacking cough and a cold at Everest base camp or I went hiking yesterday ... and now I have this weird rash. What should I do? The reality is, in the backcountry, you’re not likely to have access to a phone. [When you do,] we’re going to direct you on what the best practice is. And that’s a resource I’m really excited about because no one else in the world offers that. ... We are emergency-medicine-trained physicians. Our goal is to keep you healthy and fit and to enjoy your experience, but not at the risk of you harming yourself. And this is really responsive: The app is there to plan and prepare, and to be there for you.

2. Best pre-tailgate Super Bowl party? Head to Redondo Beach. Two things happen on Super Bowl Sunday in L.A.: Freeway traffic typically falls dramatically during the game (though maybe not this year with the big game in L.A.), and active fans start game day with the Redondo Beach Super Bowl 10K. Yep, you’ll see costumed runners dressed like football players, Lady Gaga, Batman, you name it, according to race organizers. The 44-year tradition includes 5K and 10K routes ($45 entry for either) that skirt the Redondo Beach Harbor, plus a Kids Run and 10K Baby Buggy Run. Runners also have access to a two-day Health & Fitness Expo and two free beers at the finish with live music. Check out details on the Feb. 13 event here.

3. Learn about early Mt. Everest ascents in a museum show opening in February. British climbers in the early 1920s made several attempts to climb 29,000-foot Mt. Everest. In 1922, two expedition members, who pioneered the use of oxygen at high elevation, got as high as 27,300 feet, higher than anyone else had climbed. Despite the early success, the peak remained out of grasp until 1953, when New Zealander Edmund Hillary and Nepali Tenzing Norgay successfully stood atop the highest mountain in the world. The story of the teams who tried to scale the Himalayan peak is told in the new exhibition “Everest: Ascent to Glory.” The show is a partnership between the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana and the London-based Royal Geographic Society with the Institute of British Geographers. Artifacts and photographs, including a remastered version of the 1924 film “Epic of Everest,” tell the history of the famed peak. The exhibition opens Feb. 12 and continues through Aug. 28. In addition, the museum has scheduled Everest-related events, like an online chat Feb. 19 with the first all-Black team trying for the summit ($10 to $15). Find more information about the show at the Bowers Museum website.

The must-read

The Los Angeles River, a free-flowing waterway turned into a concrete flood-control channel in the mid-20th century, is showing signs of its old self, particularly in an area north of downtown L.A. “Cottonwood and sycamore trees push skyward, while fish dart beneath the swooping shadows of cackling waterfowl,” L.A. Times staff writer Louis Sahagún wrote in a recent story. “The scents of mulefat scrub and sage hang in the air.” But there’s one thing about the river: 90% of the flow that sustains the emerging habitat is treated wastewater, which has become a precious commodity for cities amid the statewide drought. Reclaiming and recycling the runoff before it hits the river would dash any hopes of the river making a natural comeback. And the L.A. River isn’t the only green spaces that may be affected by reclaimed wastewater. Read the full story about the battle brewing over the L.A. River.

The red flag

Football players aren’t the only athletes who risk repeated concussions and brain injury in their chosen sport. Pro surfer Derek Dunfee of La Jolla is living proof of what it is to love riding big waves — but knowing what it feels like to get seriously smacked around by them. “There were other concussions as the years went by, and with them a recurring aftermath,” John Wilkens writes in the San Diego Union-Tribune. “Nausea. Headaches. Painful stabs from bright lights. Memory loss. Mood swings. Fits of rage or sadness. Then the waves called to him again, and out he went. ‘I was at the top of my game,’ he said. ‘I didn’t want to give that up.’ ” Now Dunfee and other surfers are talking about head injuries and trauma. Read the full story.

P.S.

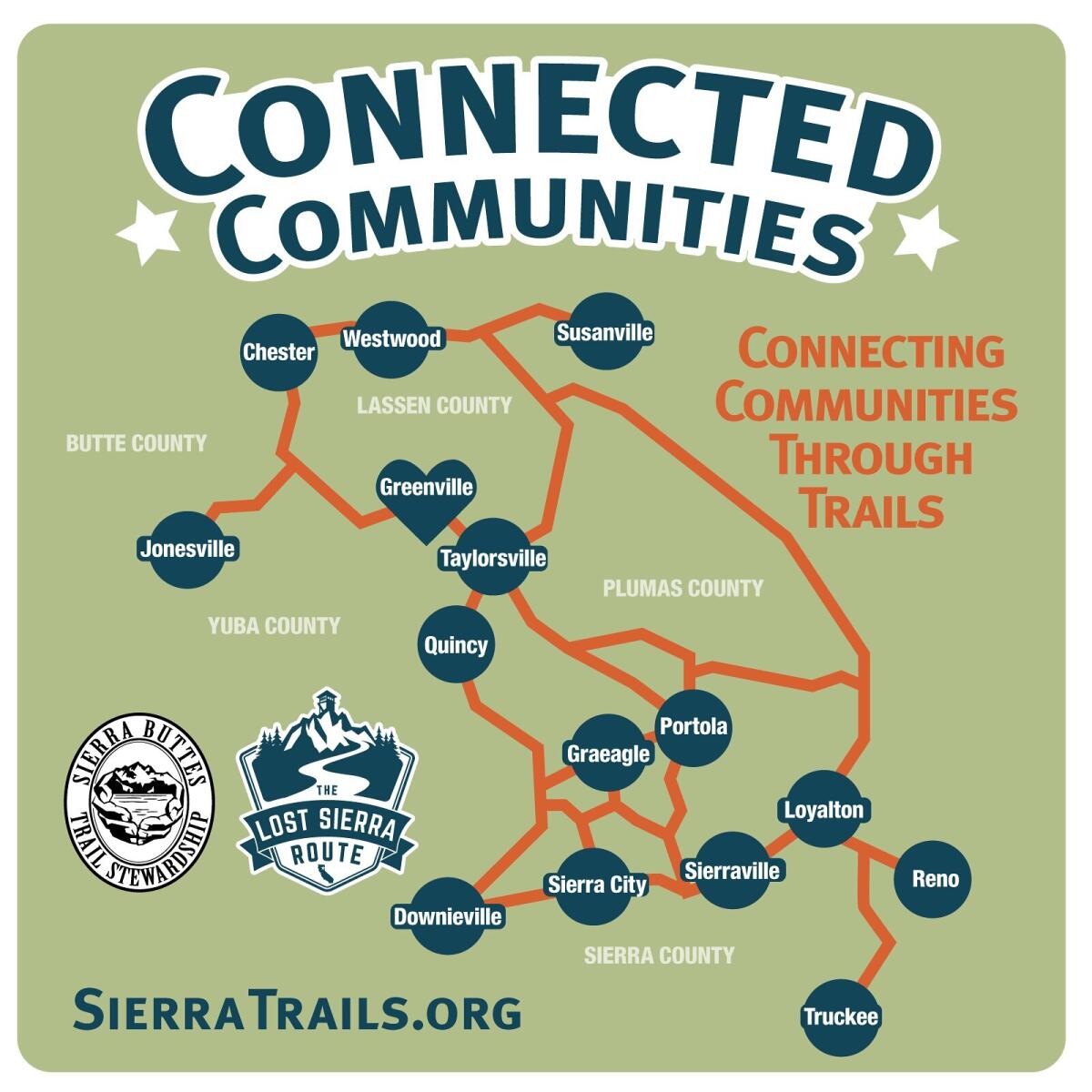

Ever heard of the Lost Sierra Trail? Likely not, because it isn’t finished. The ambitious 600-mile route aims to connect 14 towns in five Northern California counties. The route relies on existing trails as well as ones in the works to connect places like Downieville and Quincy to Chester and Susanville. It’s an ambitious project, one that starts this year and continues through 2030, with trails opening in phases. If you want to add your own sweat equity, sign on to Trail Daze events, which start in late April, with the Sierra Buttes Trail Stewardship. The nonprofit organization has been building trails in the Sierra Buttes, Tahoe, Plumas and Lassen national forests since 2003.

Send us your thoughts

Share anything that’s on your mind. The Wild is written for you and delivered to your inbox for free. Drop us a line at TheWild@latimes.com.

Click to view the web version of this newsletter and share it with others, and sign up to have it sent weekly to your inbox. I’m Mary Forgione, and I write The Wild. I’ve been exploring trails and open spaces in Southern California for four decades.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.