Venice’s famed tolerance is being tested by the homeless

- Share via

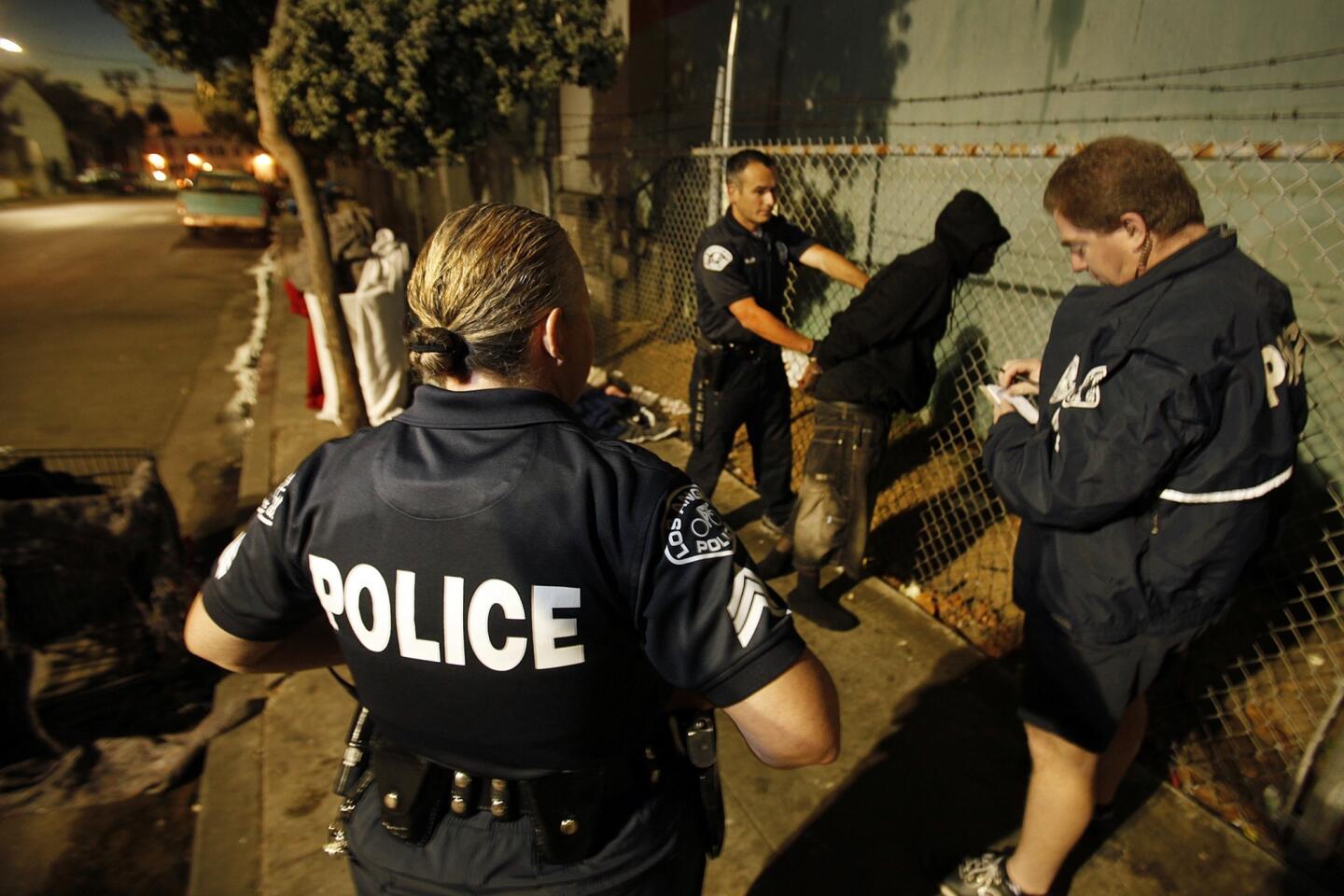

The homeless people camped outside a planned Google facility in Venice were beginning to stir when Los Angeles police rolled up around dawn.

Chesnel Dorceus was slow to dismantle his makeshift shelter and wound up briefly in handcuffs.

“Wow, blankets on a cart is a structure?” said Dorceus, 26, who was cited for illegally lodging in the street and released. “Why can’t you guys leave me alone?”

Such interactions have become routine in the beachfront neighborhood. Under a 2007 court settlement, homeless people may sleep on sidewalks in the city of Los Angeles as long as they move on by 6 a.m. When they don’t, officers find themselves on wake-up patrol.

“Sometimes I wish I had crime that was more police-related,” said Sgt. Theresa Skinner, who estimated that 75% of the complaints she deals with as a senior lead officer were about transients.

The county is home on any given night to 58,000 homeless people, according to a U.S. Conference of Mayors report. Venice long has been a magnet for transients and affluent homeowners alike — the two groups generally coexisting in a community known for embracing people on society’s fringes.

But now — with gang crime on the wane, new business ventures bringing in jobs and property values on the rise — gentrification is going strong. Homelessness is also on the rise, leading to increased tensions.

In recent weeks, officials counted 174 homeless people on Venice’s streets and 132 more at its winter shelter, a jump from a year ago, police said.

Some newer residents are quick to call police about things the old guard would have shrugged off, locals say. At the same time, young, aggressive transients — other homeless people call them “dirt punks” — are upsetting longtime residents.

Carolyn Flook, who has lived in Venice since the 1990s said she asked a homeless friend last month to help her eject a young transient from her carport. Instead of leaving, the man chased her down the driveway on his skateboard.

“He gave me the finger and was yelling obscenities,” she said. “This didn’t go on before.”

Grievances cut both ways.

Brian Connolly, an aspiring screenwriter, said he arrived at Starbucks with a sleeping bag on his back and was told he would have to take his sausage sandwich and coffee outside.

In an article he wrote in a local newspaper, Connolly accused the store of instituting “Jim Crow laws” for the homeless in Venice.

In response, Starbucks said that a blanket exclusion of homeless people was against company policy. “We spoke with our store partners and used this as a coaching opportunity,” said spokeswoman Laurel Harper.

L.A. City Councilman Mike Bonin, whose Westside district includes Venice, said it was time to move beyond stereotypes of homeless people as either victims or predators.

“All of these things are true and none are exclusively true,” he said. “When we use homelessness as a catch-all, we cannot find solutions.”

Even a modest plan to get shopping carts and tarps belonging to the homeless off the streets ran into trouble: Someone attached extra padlocks to a cargo container that had been set up for homeless people to store their property while they are at a winter shelter. The Department of Recreation and Parks had to get a bolt-cutter to free the belongings.

Deborah Lashever, a boutique owner who said she was forced off Abbot Kinney Boulevard by high rents, said NIMBYswere behind the vandalism. “They don’t want any homeless services,” she said of people with a “Not in my backyard” mindset.

Bonin pointed out that the beach town offered expansive homeless services at facilities such as the St. Joseph’s Center and the Venice Family Health Clinic.

But a public discussion about moving the homeless storage bins from behind the beach paddle tennis courts set off alarms among some residents. Bonin appeared before the Venice Neighborhood Council to calm things down after rumors that a senior center on Westminster Avenue was being converted into a homeless shelter.

“Venice is a place where controversy is close to the surface,” Bonin said later.

He also angered advocates for the homeless by telling the Los Angeles Police Commission that people in Venice were afraid of transients.

Protesters at a Martin Luther King Jr. weekend “sleep-in” for homeless rights responded with T-shirts emblazoned, “I am house-free in Venice and I am not afraid.”

During the recent morning patrol, Skinner pointed out toppled shopping carts and piles of trash left behind by encampments and public meals. But there was also a man named Al who swept his spot clean outside the planned Google site, saying: “Even though I’m in the streets, I like to be neat.”

Some of the “unhoused” accuse police of harassing them with petty tickets they can’t pay. “They’re trying to get us so frustrated to move us out,” said Gregory “Buddha” Gussner, a 1985 Venice High School graduate.

Others say police protect them from predators.

“They’re humanitarians,” said one homeless man trudging down the boardwalk.

Last weekend, Bonin announced stepped-up police patrols along the boardwalk in response both to complaints from businesses and some high-profile crime, including the December beating of a homeless man.

Also at Bonin’s request, the city started cleaning the boardwalk twice a month, hauling unattended belongings downtown. Under another court order, the city must store the property for 90 days but will return it if the owner asks.

“They come in hazmat suits, like some bad movie,” said Roberto Luis Santana, 52, an actor. “Those monies should be put into funds for housing for people.”

Bonin too wants to see more housing, with medical and mental health services, to help homeless people reenter society.

But U.S. Housing and Urban Development vouchers are frozen, and the city added only 771 permanent supportive housing beds last year.

“Looking to the city to solve homelessness is like asking your plumber to rewire your house,” Bonin said.

Google has given grants to Venice homeless agencies. When the tech giant moves into the new facility complex, police expect the homeless will scatter, then turn up somewhere else.

“We’ll never make enough arrests or write enough tickets to get rid of homelessness,” Skinner said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.