Q&A: Winter rains bring new wildfire dangers in Southern California

- Share via

Richard Minnich didn’t have to go far on a recent weekday morning to find an immense fire hazard surrounding the resort town of Lake Arrowhead and nearby communities in the San Bernardino Mountains.

Standing on a roadside pullout, Minnich eyed the culprit: a dense forest of pines and thickets that gives an alpine look to Lake Arrowhead. The site, historically known as Little Bear Valley, is home to about 12,000 permanent residents and attracts summer crowds of up to 80,000.

The unbroken vista of lush green is the result of more than a century of fire suppression. Each time firefighters put out a small blaze, unburned brush and timber was left to fuel future fires.

“People here want to live . . . in the majesty of nature,” Minnich, a fire ecologist at UC Riverside, said with a sigh. “But the forest all around them is ripe for a massive fire that is going to wipe it out and take thousands of homes nestled in the woods along with it.”

Minnich, 71, forecasts the probability of fire risks throughout Southern California based on meteorological and historical records, aerial photographs and ecological studies.

With the long Memorial Day weekend approaching, The Times grabbed a stump and listened to Minnich’s predictions for Southern California’s 2017 fire season.

Looking at the data, what is this year’s outlook?

Wet winter increases the risk for early fires in grassy hillsides, followed by postponed chaparral and forest fires in areas that have not burned for more than a century.

What about places, like Los Angeles County, where open grasslands and the suburbs clash head-on?

Grass that flourished on hillsides during the rains is already drying out and becoming kindling for extensive and frequent fires in places such as the Perris Basin in Riverside County, the Puente Hills-La Habra Heights area in eastern Los Angeles County, and the rolling hills of the northern San Fernando Valley.

Other grasslands close to homes are west of Los Angeles and northward into Ventura and Santa Barbara counties.

The good news is that if the grass doesn’t burn this summer, it will break down in the next winter rains.

Unlike grass, which has a life cycle of about one year, stands of forest and chaparral cycle in periods of decades. The problem in places such as the San Bernardino Mountains is that for more than 100 years we’ve tried to eliminate fire as a natural mechanism of breaking down all that organic matter.

Where is the risk of wildfires lowest?

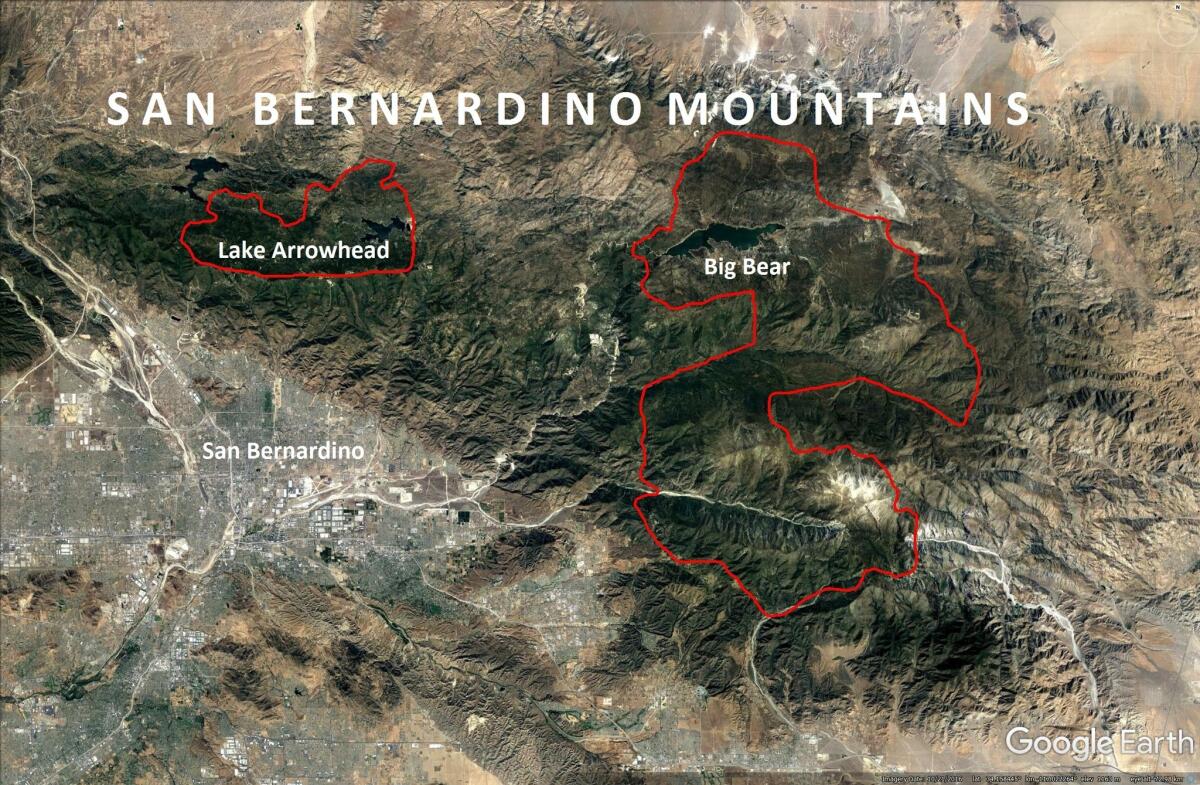

Areas that have less risk already burned fires over the past 10 to 20 years. They include much of the chaparral in the western San Bernardino Mountains and most of the San Gabriel Mountains, with the exception of the Sierra Madre and Mount Wilson areas, which haven’t burned since 1924.

Should firefighters just give up, knowing that fire is inevitable in forests of old trees towering over thickets?

Here’s the ecological bottom line: The more burns in a given forested area, the smaller and more manageable fires will be in the future.

Why are you so edgy about Lake Arrowhead?

Lake Arrowhead has not burned since 1879. So, the thick forest of old pines towering over thickets of younger trees and chaparral there is capable of burning the entire forest to the tree tops. This is what happened in a San Gorgonio Mountain fire in 2015, where nearly 10,000 acres were charred, leaving a massive gap in the forest that will persist for a century or longer.

So Lake Arrowhead’s been lucky?

The wildlands north of Lake Arrowhead and the town itself emerged unscathed after the devastating Old Fire in 2003, which burned south of it, to the west near the community of Crestline and the east near the community of Running Springs.

More than 300 homes were destroyed in Cedar Glen, about three miles east of the town of Lake Arrowhead.

The fact that the town of Lake Arrowhead was spared was itself a gigantic event.

Over the years, millions of trees have been removed from the Lake Arrowhead area. But there remains such an extremely dense forest in that area that I believe it faces the worst risk of forest fires in Southern California.

Didn’t our recent heavy winter rains make trees and brush less flammable?

Yes, up to a point.

The overall fire hazard varies year by year, depending on winter rainfall. For example, the onset of fire season comes later in summer and fall after a wet winter, and arrives earlier in spring and summer after dry winters like the ones we had during the recent five-year drought.

Regardless of rainfall, however, the fire hazard in a specific region is defined by its fire history and the effect it has had on the landscape.

That’s because fires preferentially burn old chaparral and conifers. Hence, the oldest stands of trees are always the next in line to burn.

Which areas face the greatest risk for forest fires?

I’m most concerned about communities in pine forests that haven’t burned since the 19th century: Big Bear Lake and Lake Arrowhead in the eastern San Bernardino Mountains, and Idyllwild in the San Jacinto Mountains.

These areas have hundreds of trees per acre with trunks more than 4 inches in diameter and an understory of young conifers and brush. By way of comparison, a healthy, safer forest has about 13 such trees per acre.

The oldest stands of trees are always the next in line to burn.

— Richard Minnich, fire ecologist at UC Riverside

In the event of a fire, the heavy understory will create what foresters call a “fuel ladder” that sends flames climbing up into the canopy, triggering a massive blaze.

Also worrisome are stands of chaparral blanketing the San Bernardino Mountains east of Redlands, which haven’t burned in 60 to 120 years. This situation predicts future burns in those areas for decades to come.

Twitter: @LouisSahagun

ALSO

Chapman awards honorary degree to mom who attended every class with quadriplegic son

L.A. bus ridership continues to fall; officials now looking to overhaul the system

UPDATES:

12:36 p.m.: This article was updated with additional information about Los Angeles County’s fire risk and other details.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.