Massive desert solar plant opens, already a threatened species

- Share via

IVANPAH VALLEY, Calif.— The day begins early at the Ivanpah solar power plant.

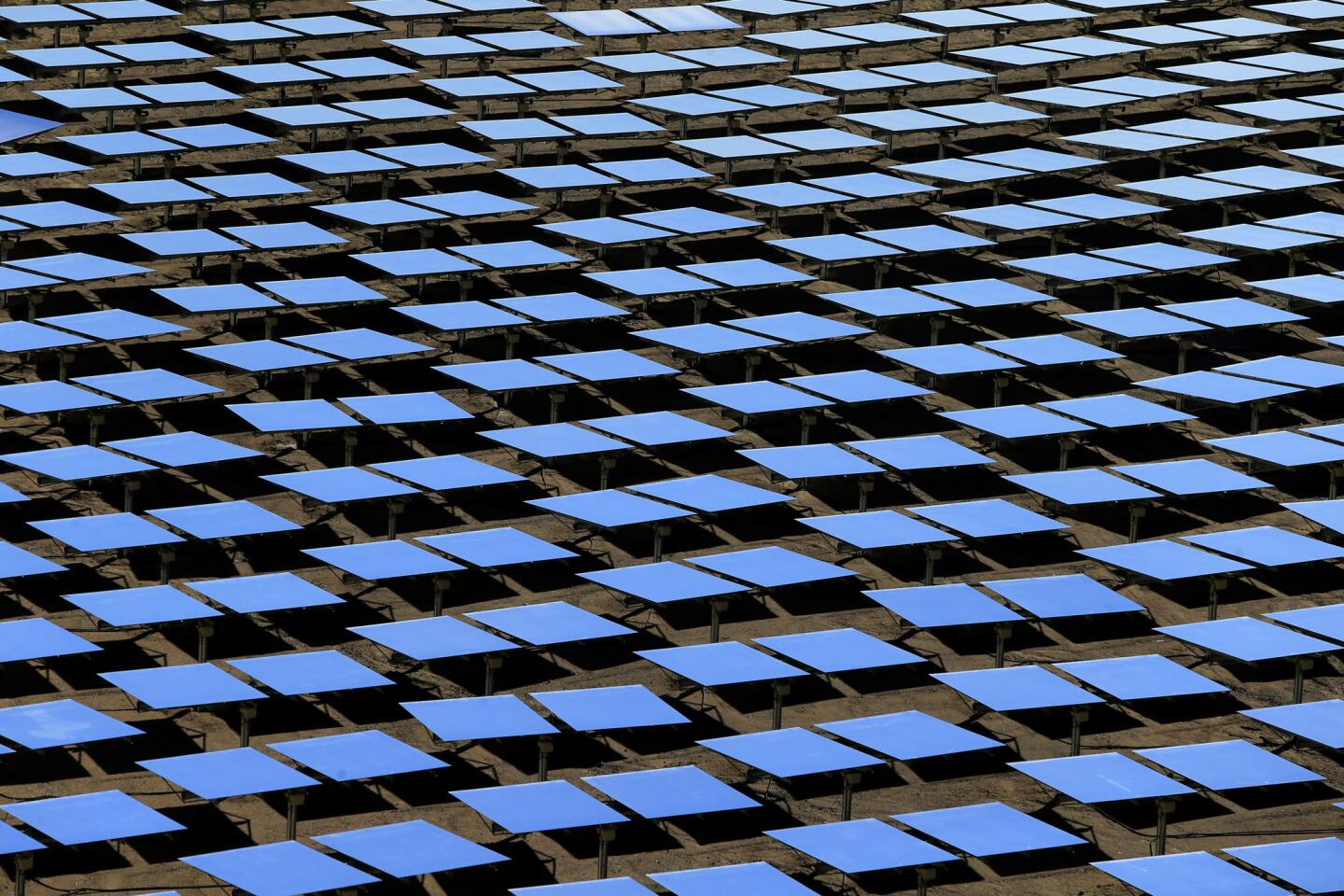

Long before the sun rises, computers aim five square miles of mirrors to reflect the first rays of dawn onto one of three 40-story towers rising above the desert floor.

The 356,000 mirrors, each the size of a garage door, focus so much light on the towers that they pulsate with a blinding white light.

At the top of each tower is an enormous boiler where the sun’s energy heats water to more than 1,000 degrees, creating steam that spins electricity-generating turbines.

Ivanpah is the largest facility of its kind in the world. Unlike conventional solar plants, whose panels collect sunlight and convert it into energy through photovoltaic cells, the mirrors here follow the sun as it arcs across the sky, reflecting energy rather than absorbing it.

The effect is stunning to the eye.

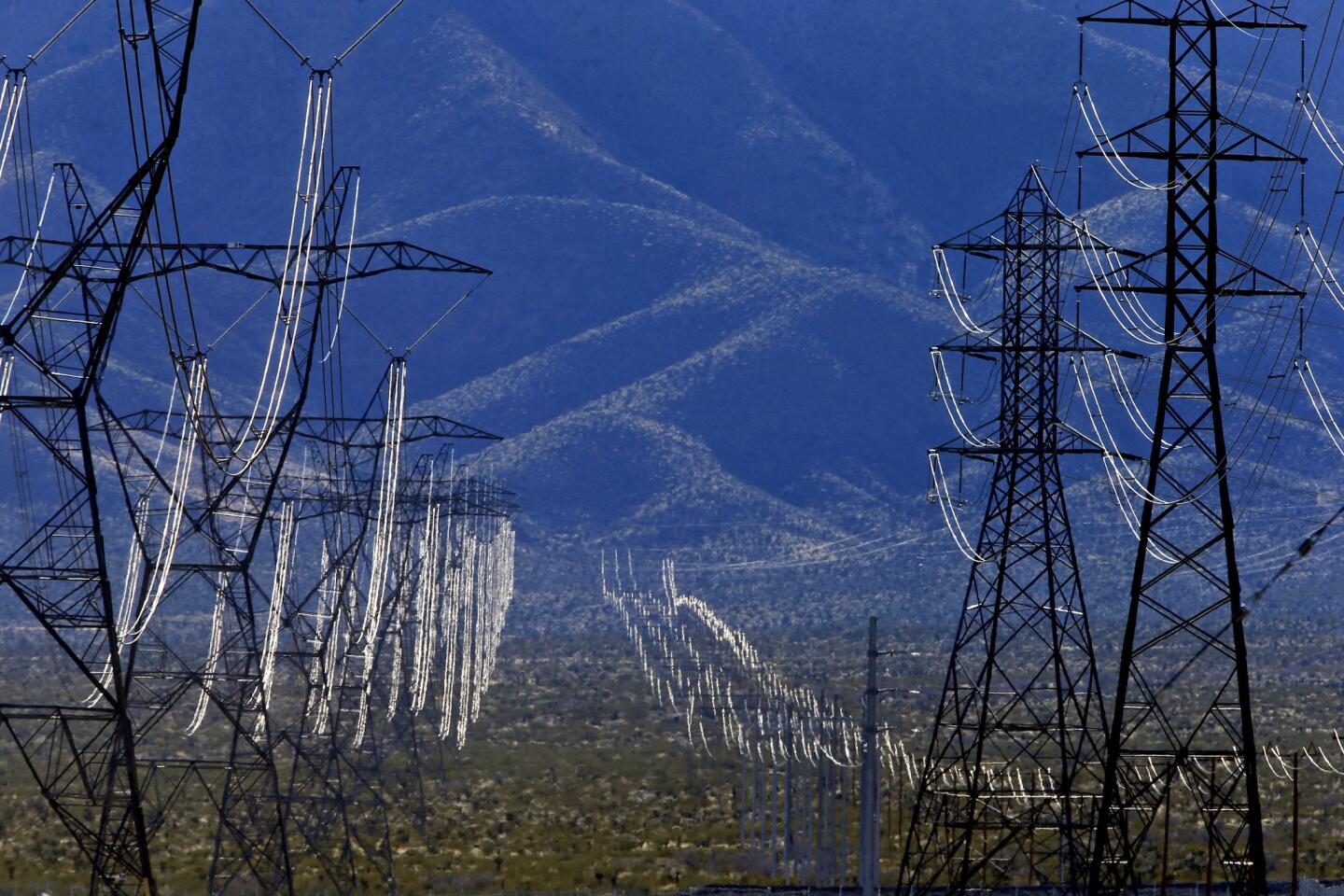

Outlined against the backdrop of the Clark Mountains, the Ivanpah power plant shimmers like a mirage, in full view of motorists on Interstate 15 heading to Las Vegas.

After nearly four years of construction that killed desert tortoises, burned the feathers off passing birds and mowed down thousands of acres of native flora, Ivanpah officially opened last month with a gala that included a rock band and a horde of dignitaries — Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz among them.

Despite the gaiety, the event was tinged with the recognition that Ivanpah could be the last of its kind in the U.S. The plummeting price of photovoltaic solar panels, cheaper natural gas and evaporating federal assistance have made it financially shaky to embark on such large-scale projects.

Officials from New Jersey-based NRG Energy Inc., which co-owns the plant, stated flat-out that if not for a federal loan guarantee, the $2.2-billion project would not have been built.

The last of those government breaks, an investment tax credit, expires in 2016. NRG and BrightSource Energy, which designed the plant, have slashed their once-ambitious slate of projects in the U.S. and say that they are taking their business to more favorable markets in China, Africa and the Middle East.

NRG Energy’s chief executive, David Crane, remarked at an energy summit in New York last spring that the trend to larger solar plants was “idiotic.”

::

Ivanpah began producing power to the grid in January, albeit intermittently.

According to the state’s Independent System Operator, the plant provided no power on some days and 20% to 40% of capacity on others.

Officials with NRG said the reduced power output was just a matter of “growing pains,” adding that they were pleased with Ivanpah’s performance during commissioning.

In winter months, they said, the plant will be expected to operate at 20% of its capacity; during peak months, it will deliver about 45% of its 370-megawatt maximum, in line with industry norms.

It was never certain that Ivanpah would ever get up and running. Detractors harped that such a large concentrated solar power plant had never been built.

Oakland-based BrightSource Energy Inc. had emerged from the bankruptcy of its parent company and required a $1.6-billion federally guaranteed loan to finance construction. Like other renewable energy projects, the company negotiated power purchase agreements with major utilities at rates double that of conventional energy plants.

Some conservation groups questioned the choice of the site, pointing out a suite of threatened and endangered species in the region and asking the federal government to rescind its lease on 3,500 acres.

BrightSource prevailed, but spent more than $50 million to install specialized desert tortoise fencing.

Some native plants were inventoried, removed and placed in an on-site nursery. Workers took note of precisely how each plant sat in the landscape and replanted them with the same orientation to the sun.

A major concern for federal biologists was how the mirrors and three massive towers might affect birds. It remained an unanswered question until the facility began operations.

According to documents filed with the California Energy Commission, nearly four dozen bird carcasses were found at the site with burned feathers and wings during the three-month commissioning process, which ended in December. Among them were a peregrine falcon, two hawks, nighthawks, a grebe and warblers and sparrows.

Biologists are in the process of a two-year study examining the plant’s role in avian mortality.

::

Producing electricity at Ivanpah is a delicate ballet of sun and mirrors.

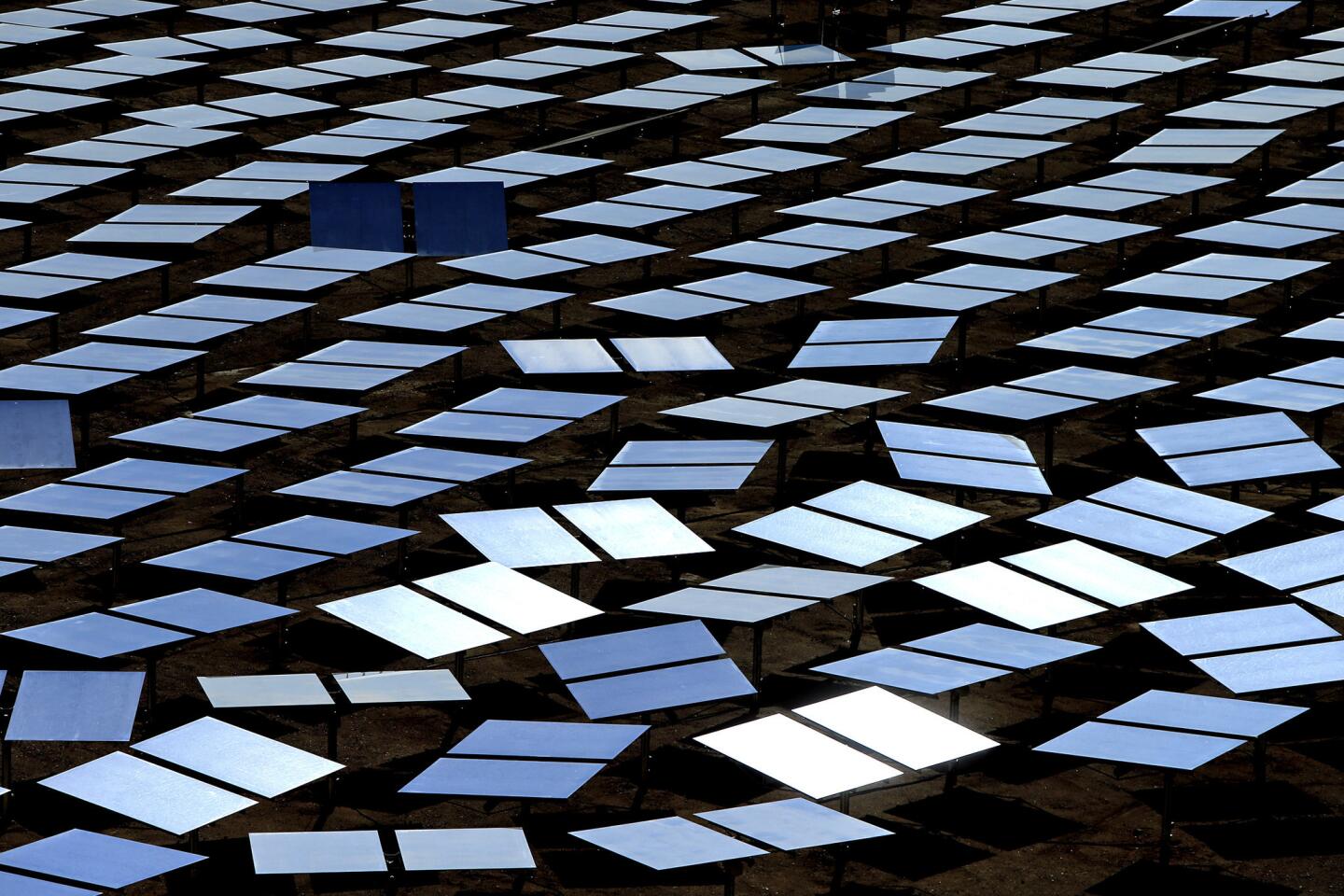

The mirrors, mounted on frames known as heliostats, wake in the morning from their stowed position and focus the sun on the towers under the guidance of a central computer. The computer positions each mirror, taking into account the time of year, where the sun is on the horizon and the expected time of sunrise.

Each mirror has an assigned focus area based on a mathematical model. If the mirror is not on target, it is repositioned by an electronic motor that emits an audible chirp with each adjustment, a digital pulse that telegraphs its position to the computer.

Because of the Earth’s movement through the day, corrections need to be made every 10 minutes.

An infrared camera trained on each of the plant’s three boilers determines how much energy each section of the receiver is generating and, if needed, the computer will change the heliostat alignment to ensure the proper temperature.

At Ivanpah, the quality of steam is an important issue. Massive evaporators remove water droplets from saturated steam because, to protect the spinning turbine blades and for peak efficiency, the vapor must be nearly devoid of moisture.

Dave Beaudoin, project manager for NRG, bragged that the plant’s steam is “more pure than angel tears.”

Depending on the conditions, not all the mirrors are aimed at the boiler. These spare mirrors are ordered to focus on a single point in the air near the boiler. It is this concentrated light that sometimes creates a misty gauze around the towers.

On the ground, the mirror field encircles the tower but not in concentric rings. Instead, the pylons have been laid out in a random pattern to avoid casting shadows on other mirrors.

As the sun sets each night, the field of mirrors goes into a slow-motion shutdown.

After spending the day in pursuit of the sun, the mirrors fold up for the night like a field of drooping flowers, placed in mechanical sleep until another dawn.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.