To create a campaign to combat record STD rates, Long Beach turns to art students

- Share via

In a large white studio in Pasadena, nine art students scrutinized a wall they had covered with cartoon condoms and colorful depictions of chlamydia. They had a health crisis to solve, and one of them had just begun to explain how art was the answer.

Then instructor Dennis Lee cut her off.

“This just looks like design for design's sake,” he said. “Every time you show an idea, you have to reinforce it with insight.”

Tough love and critical thinking go hand in hand on the third floor of the ArtCenter College of Design, in Designmatters, an unusual incubator that pairs art students with complicated social issues. Each class is assigned a real-world big client with a real-world big problem — and given 14 weeks to come up with a way to help solve it harnessing the power of art and design.

Long Beach health officials had come to Designmatters with a vexing dilemma: how to stem an alarming increase in cases of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV in a generation that seems apathetic, far removed from the last-century fears of the AIDS crisis.

STD and HIV cases have increased nationwide and gone up and down California. And Long Beach now has the state’s second-highest rate of chlamydia and third-highest rates of gonorrhea and syphilis. No one factor explains the increases, but health officials point to the popularity of online dating apps, casual hookups and evidence that young people who are busy and otherwise healthy often don’t bother with condoms or routine checkups.

What would it take to change that, to motivate the right audience and raise awareness without shaming Long Beach as a hot spot for STDs?

The city’s health department, hoping to launch its first campaign in 2018, decided to put the question to students rather than a traditional consulting firm.

The projects produced by Designmatters — reimagining burn clinics for children in Chile, raising awareness about cervical cancer among Latinas — have earned ArtCenter NGO status from the United Nations, the only design school so recognized.

At a time when many young people feel a call to activism, Designmatters students learn how much hard work it takes to understand and empower others.

“Always go back to the person you’re trying to help,” Lee told the class. “We’re here to solve a very specific human problem.”

Instructor Tyrone Drake emphasized “cultural immersion,” not “scare tactics.” Meet people, he told the students. Frequent popular hangouts. Build trust in order to gain insight not visible in the numbers alone.

“The whole idea is to get more authentic feedback from people on the street,” he said, “as opposed to us giving them information and making them feel like we're preaching to them."

For the first few weeks, students explored the city and their own perceptions and misunderstandings about STDs and HIV. They discovered that Long Beach felt like a small town. They learned that syphilis often has no symptoms.

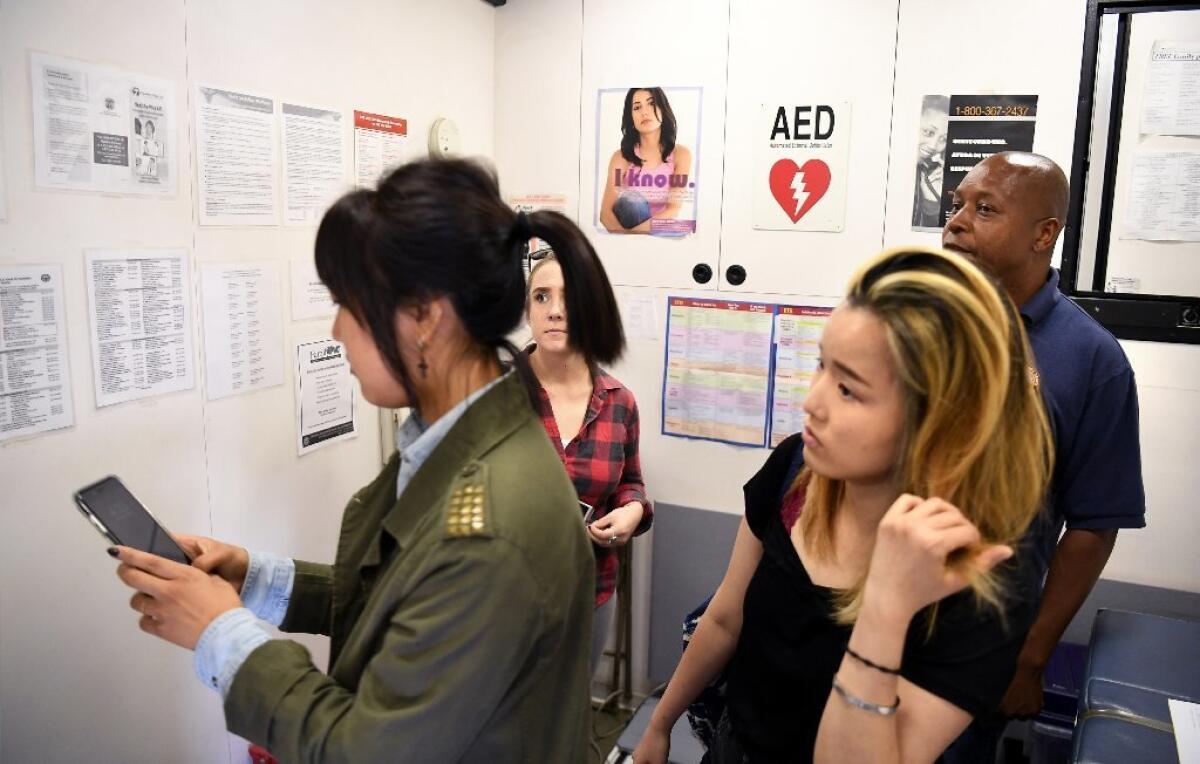

Crammed inside the city’s mobile clinic, which offer residents free checkups, student Riley Gish, who had gone from illustration to a major in product design, snapped photos of the faded posters on the van’s walls.

“If I was coming into a place like this, where I’m already scared about what’s going on with my body,” she said, “I mean, it feels so drab and a little broken down. Very clinical. And that’s not an environment that makes you feel like you’re going to be OK.”

Later, as she and her classmates visited the city’s health department, they stumbled into a hidden corner. Past the nondescript lobby, past the sterile waiting area, back where the nurses met their patients, they laughed out loud and immediately took to Instagram to share colorful hand-drawn signs with blunt, funny messages: “R U A Fool? Cover your tool!”

“Where’s that humor outside these walls? It’s like two different worlds,” student Amy Huang, who studies graphic design, asked the nurses. “Have you tried bringing that into your campaigns?”

Such fresh perspectives are key, said Mariana Amatullo, who co-founded Designmatters in 2001. What began as a concept evolved into a full academic department increasingly sought after by both students and companies.

About 80% of Designmatters projects have had at least some elements implemented, Amatullo said, and students often go on to become social entrepreneurs or get hired as design consultants. One became lead designer for UNICEF.

“There is a real demand in society for people who understand how issues are interrelated, who have been exposed to working with constraints, with complexities and very volatile social and political situations,” she said.

By week seven, the students could recite STD symptoms and knew every sex shop in town. They had hung out at bus stops, chatted with people on dating apps, met a man in his 40s who had been diagnosed with HIV. They had learned that stopping strangers on the street isn’t easy — particularly to talk about sex.

What really stood out was people’s pride in their city, said Gish, whose interests in public health and art therapy had drawn her to the project. “That’s something we're really interested in tapping into: How can we leverage that love ...”

The students, in lieu of midterms, presented five campaign concepts to city health officials. One group took a subtle approach to building awareness around town, with the slogan: “Know more about STDs so there will be no more STDs.” Another used cartoon images to depict body parts and protected sex practices — to convey information without the awkwardness of words.

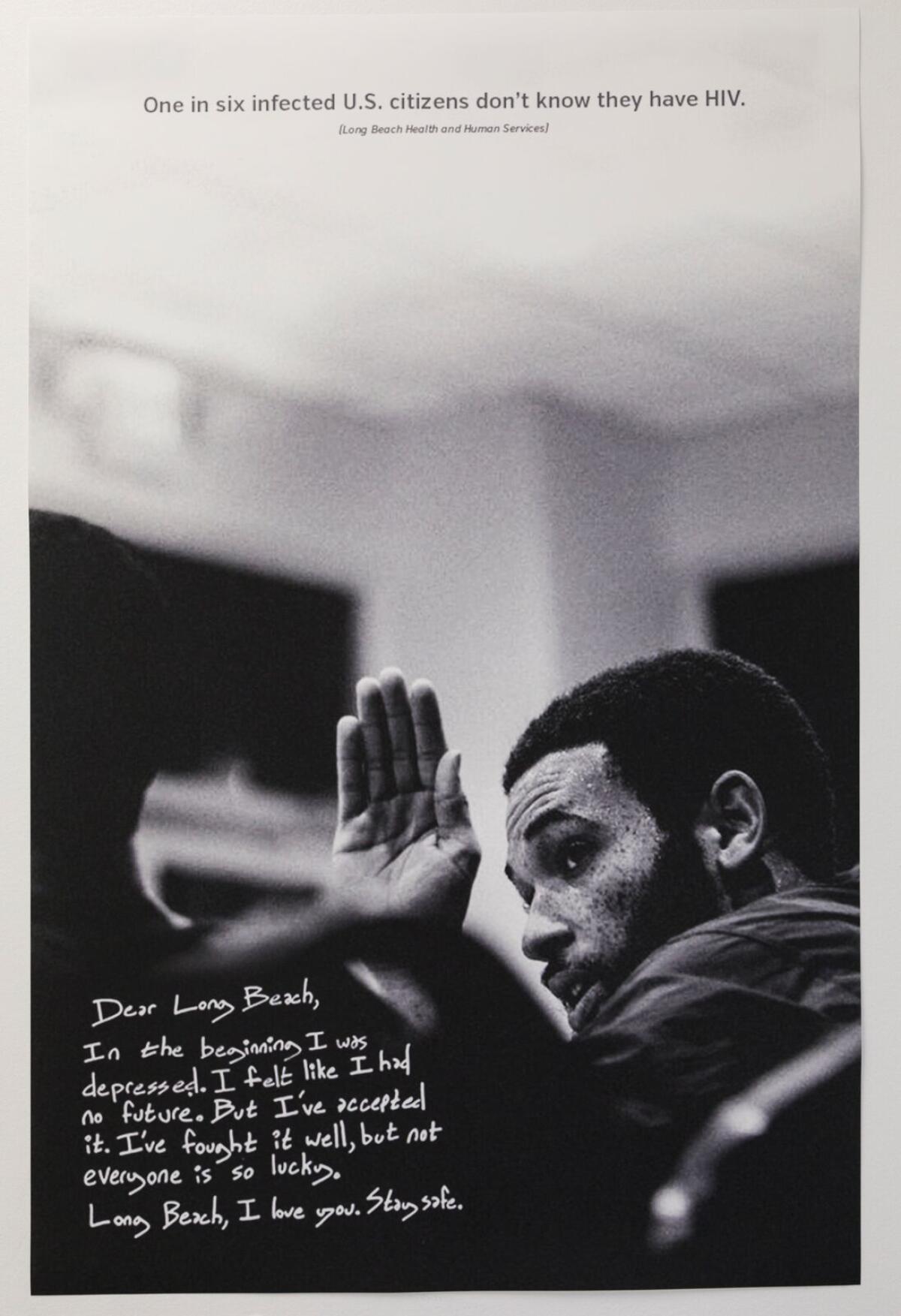

Gish’s group, who called their campaign “Dear Long Beach,” tapped into their sense that residents liked community-oriented messages that neither embarrassed nor felt too sterile. In a series of posters, they paired an image with a surprising fact (“There is no cure for herpes, only medications that help with outbreaks”) and a personal story, in letter form, from one of the many people they’d interviewed.

“Dear Long Beach, I was with him for a long time before I knew. I was sure I didn’t have anything,” Gish said, reading one letter out loud. “It wasn’t like, ‘Oh I’m sleeping around and not using a condom.’ … When it happened, it was really shocking and painful. I was lied to by someone I was with for years and really, really loved and trusted.”

The room was silent as people took in the words. Gish pointed to the bottom of the poster, which urged viewers to read more, share personal stories, perhaps get tested.

The final weeks were tense, as five concepts boiled down to two: “Dear Long Beach” and “Know More.” Students argued over typeface and built mock-ups of websites. They created examples of how their messages could be used on murals, T-shirts, stickers and social media.

They tested their ideas on Facebook and pitched them to people in bars. They wanted to be provocative, but not offend or discourage participation.

At 3 a.m., hours before final presentations, they were decorating ArtCenter bathrooms and hallways to show how their campaigns could work in public spaces. “If it was just a class, I don’t think we would have tried this hard,” said Sam Yen, from the “Know More” campaign.

When the big moment arrived, Gish held her breath. She watched the health officials snap photos of posters and put stickers on the backs of their phones.

Then it was her group’s turn to present the final version of “Dear Long Beach,” which used grainy black-and-white portraits of real people with illustrations artfully masking their identities.

“‘Dear Long Beach’ is an ode to the city. … It brings the raw, human experience back into an otherwise clinical topic,” Gish said. The goal is to leverage personal stories, remove the shame and empower more people in the community to share their stories and opt for healthier behavior.

The “Know More” campaign was edgier. Some of its posters appeared to be blank — but explained in light text only visible up close that STDs often have no symptoms. Others stressed the risks of hookup culture.

“Your boyfriend loves receiving oral sex from his co-worker, his Uber driver, the bartender, that girl in his math class, and you,” read one, which also bore a stark warning in one corner: “1 in 2 sexually active persons will contract an STD by the age of 25.”

“It’s very clever. It’s very hard-hitting,” said Kelly Colopy, the city’s health and human services director, who said she was amazed by the insight the group of artists and designers had gained.

She went back to her office, got a budget approved and hired an ArtCenter student to help fine-tune and roll out both concepts.

On her walls, once blank, she put up some of the work. No one else in health, she said, would have a campaign so fresh and with so much potential.

Follow @RosannaXia for more education news

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.