As more Cambodian and Vietnamese immigrants are targeted for deportation, advocates say they ‘can’t stay silent’

- Share via

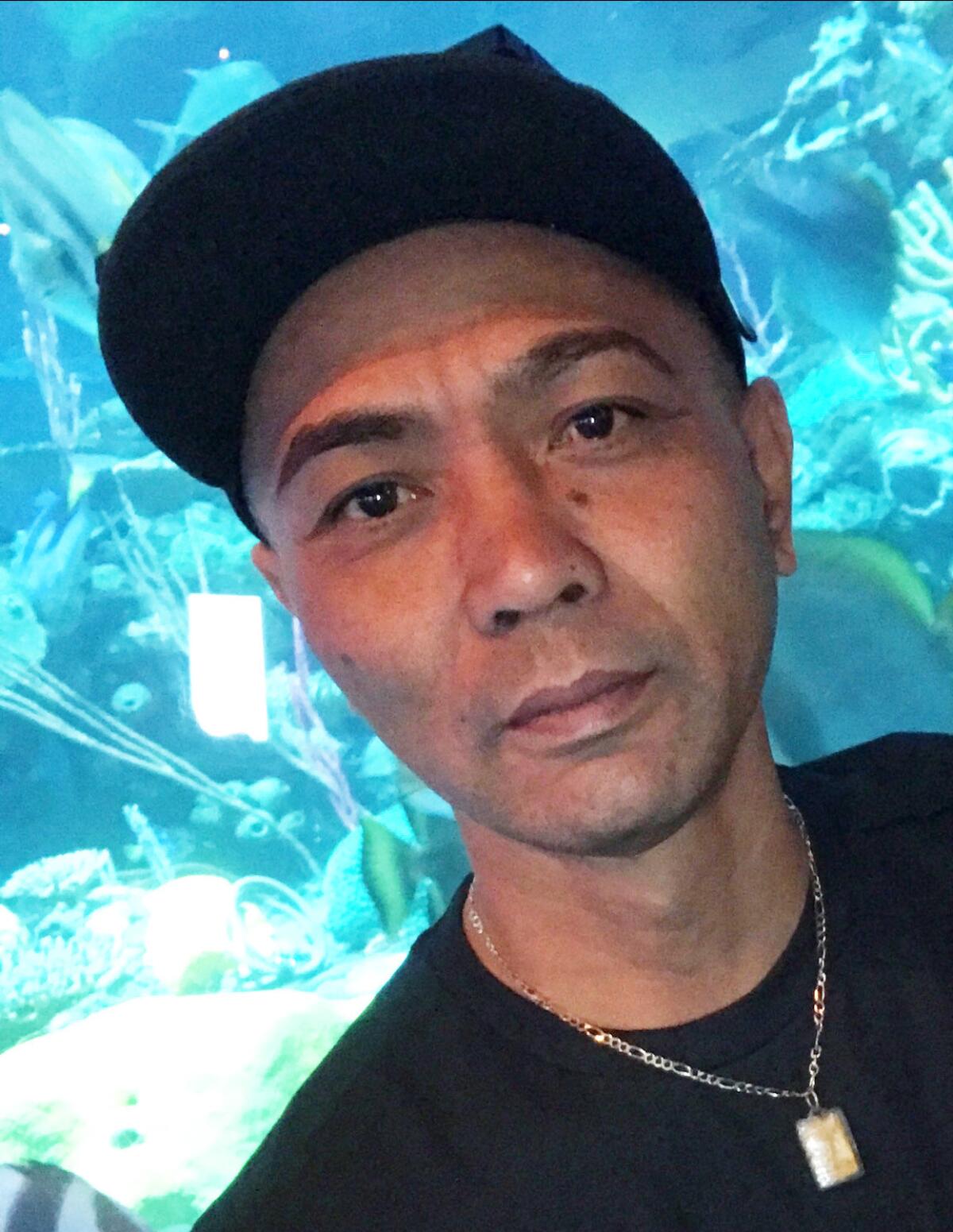

Every day, Victoria Martinez’s 2-year-old son peppers her with questions about the disappearance of his father, a Cambodian immigrant.

“Where is Daddy?” Shawn Ly asks his mom. “When is Daddy coming home?”

She doesn’t know how to answer. She sobs often.

Martinez’s partner, Sreang Ly, was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement in early October. Ly, who had a prior conviction for illegal possession of guns, was one of more than 200 people of Cambodian and Vietnamese descent detained this fall as the Trump administration has stepped up its efforts to deport immigrants with criminal records.

Most associate Trump’s rhetoric about deportations with Latinos, given his vows to build a border wall, his assertions that Mexican immigrants are “rapists” and drug dealers, and his previous calls to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program for immigrants brought to this country illegally as children, most of whom are Latino.

But immigration activists say the roundups of people of Cambodian and Vietnamese descent are unprecedented and have sparked anxiety in Asian immigrant communities.

“People may think it’s just Latinos being threatened when it comes to deportations. But there are all sorts of immigrants affected, and we can’t stay silent,” said Laboni Hoq, litigation director for the Los Angeles chapter of the civil rights organization Asian Americans Advancing Justice.

“This is a political issue. The administration is cracking down to deliver on campaign promises, and they are going community by community to make their actions known.”

The San Francisco and Los Angeles chapters of Asian Americans Advancing Justice, along with the law firm Sidley Austin LLP, filed suit in October against the federal government, alleging the Cambodian immigrants were illegally detained and should be released.

After the detainees learned the government would begin removal proceedings on Dec. 18, U.S. District Judge Cormac J. Carney issued a temporary restraining order halting deportations to give the court time to consider the “complex issues” involved in the lawsuit. On Thursday, Carney granted an injunction that will extend the stay of deportation until at least Feb. 5.

Brendan Raedy, an ICE spokesman, said the agency does not comment on pending litigation.

Family members whose loved ones are sitting in detention feel an urgency to speak up about their concerns and try to dispel preconceived notions about Asian immigrants.

“Sometimes Asian communities are ignored because we don’t think of Asians as getting deported,” said Posda Tuot, whose cousin, Kim Nak Chhoeun, was detained in October. “They’re the good ones, pursuing their own thing on the side. So when something bad comes up, we must lobby to create understanding for their situation.”

Sean Commons, a partner at Sidley Austin, said he hears “multiple stories of people changing their lives, becoming pillars of their communities, and then suddenly they get picked up and they’re gone. Why? They should give people notice. These folks are not a danger or a flight risk. They’ve been around for years and years and many have parents, spouses or children who are U.S. citizens. Why break up families?”

Cathee Khamvongsa of Modesto said in October, ICE agents detained her 42-year-old husband, Mony Neth, who was convicted of possessing stolen guns when he was 20.

At the time he was arrested, Khamvongsa said, Neth was active in church and did volunteer work, feeding the homeless. Gov. Jerry Brown pardoned Neth last month.

“Asians have to fight back loudly, not stay underground as we have done for many years,” she said. “If you’re not visible, you don’t have political power.”

Many of the Cambodians represented in the class-action lawsuit fled Cambodia as children in the 1970s, when the Khmer Rouge launched a years-long campaign of genocide that killed nearly 2 million people.

Although many of the detainees have prior convictions, years of living and working in the United States allowed them to establish roots and become lawful permanent residents, advocates say.

“What’s so shocking here is many people who have been detained have been leading quiet lives, transforming their lives,” said Jenny Zhao, an attorney with Asian Americans Advancing Justice’s San Francisco-based Asian Law Caucus. “But this administration has been aggressive going after them. It’s very much in line with their xenophobia.”

More than 1,900 people of Cambodian descent are subject to immediate detention and deportation, according to ICE. Of those, about 1,400 have criminal convictions.

Cambodia has a history of not accepting deportees, and many Cambodian nationals who otherwise would have been deported have remained in this country legally on supervised release.

Zhao said she worries more Asians will be targeted for deportation as Trump settles into his second year of his presidency.

“We’ve never seen anything on this scale before with the administration pushing countries so hard to take people back,” she said.

For the families of the detained, the last few months have been agonizing.

Victoria Martinez, who lives in Fontana, has been left alone to raise 2-year-old Shawn and his newborn brother, Benjamin, since Sreang Ly was detained.

“I am one person trying to handle two lonely children who really miss his touch and his voice,” Martinez said, sobbing. “We kept hoping he would be home for the holidays or after the holidays. And now — will it ever happen?”

Twitter: @newsterrier

UPDATES:

Jan. 27, 6:30 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details and news of the injunction.

This article was originally published Jan. 25 at 4 a.m.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.