Ban on same-sex couples roils small Christian college: ‘This isn’t something sinful, God’

- Share via

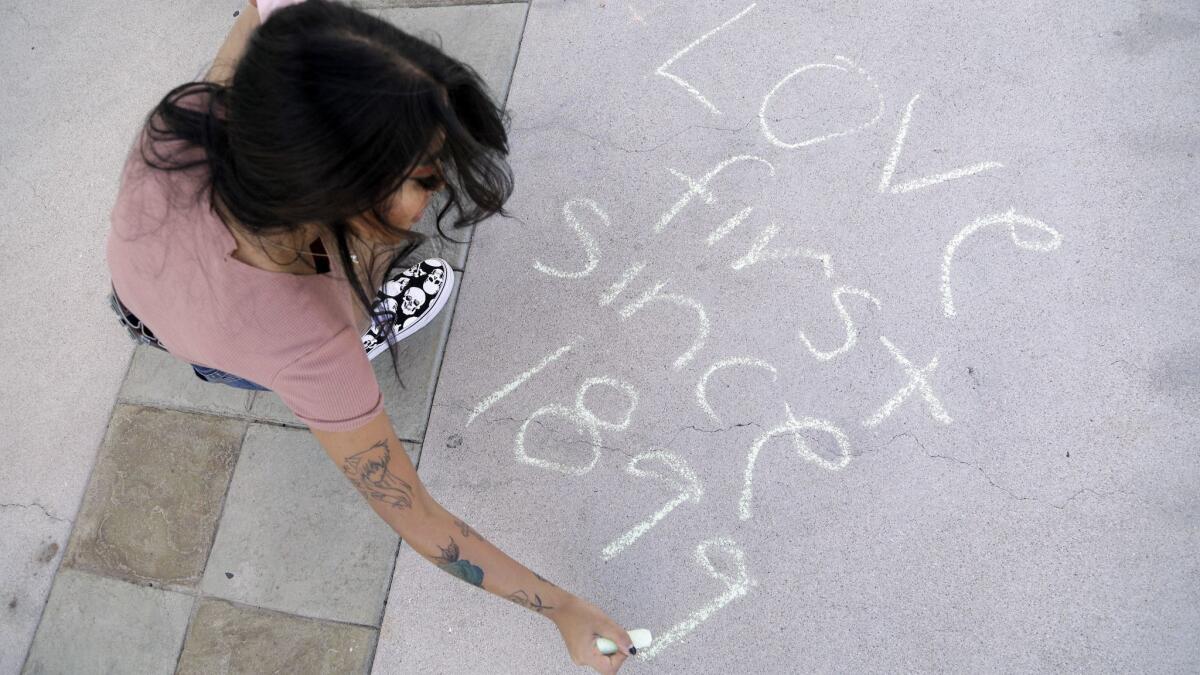

On a recent fall day, a group of protesters gathered in a university courtyard, many holding rainbow flags. About 100 students and faculty members were fighting for LGBTQ rights on campus.

The scene was unusual, though — in some ways radical — given that the location was Azusa Pacific University, a Christian college, and that the debate was over how God would view the issue of same-sex couples.

“This isn’t something sinful, God,” one student said, leading the emotional gathering. “This is something beautiful. I pray that we continue to live out the mission of being difference-makers, God, that this world be a place of equality, God.”

The public display of support for LGBTQ students was a response to the evangelical Christian university’s recent decision to reinstate its ban on same-sex relationships. The school had quietly removed the ban in August and created a new LGBTQ pilot program, which includes the creation of weekly student meetings backed by the university.

But following criticism from conservative Christian media, the university changed course, saying there was a “miscommunication” between the college and its board of trustees.

The university said the board never approved the change in the student conduct code and assured students, faculty and staff that the school’s conservative beliefs remain intact: “We affirm God’s perfect will and design for humankind with the biblical understanding of the marriage covenant as between one man and one woman.”

The move has sparked protests and much debate on the small campus in Azusa and offered a window into how the gay rights struggle is playing out in the Christian university world.

USC professor Alison Dundes Renteln said the conflict shows that while gay marriage and equality have become significantly more accepted in broader society in recent years, that change has come more slowly in Christian communities such as Azusa Pacific.

“Most people think it is equality that has prevailed now,” she said. “People think progress is linear, but there’s a back and forth. There are movements, there’s backlash,” she said.

Pepperdine University, a Christian liberal arts college in Malibu, found itself the subject of a lawsuit when two female basketball players accused the university of harassing them because they were dating. The players asserted that the school forced them to leave the basketball team and give up their scholarships, but in 2017, a federal court ruled in Pepperdine’s favor, saying there was not enough evidence to determine that the university had targeted the women based on their sexual orientation.

Religious colleges in California have taken different tacks in addressing same-sex relationships among students, often opting for vague language that discourages sex out of marriage regardless of sexual identity.

Pepperdine opposes sex out of wedlock in general but supports students “who experience same-sex attraction and gender dysphoria,” according to its student code of conduct.

Biola University, an evangelical Christian college in La Mirada, says it is committed to “engaging this conversation with courage, humility, prayerfulness and care,” adding, “We believe, in accordance with Scripture, that we are all broken.”

On the other hand, Loyola Marymount, a Jesuit university near Playa Vista, has no policy on same-sex students or relationships.

Other Christian colleges across the country have enacted policies allowing LGBTQ faculty.

Not long after the 2015 landmark Supreme Court ruling that legalized same-sex marriages, Eastern Mennonite University in Virginia and Goshen College in Indiana added sexual orientation and gender identity to their nondiscrimination policies, allowing faculty in same-sex marriages to work on the campus.

The two schools were members of the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities at the time, and their action prompted two other universities to withdraw from the organization in protest. Months later, Eastern Mennonite and Goshen College also withdrew their membership.

When it comes to LGBTQ relationships on campus, though, Azusa Pacific University has a more explicit policy: “Students may not engage in a romanticized same-sex relationship,” the code of conduct states.

The consequences aren’t clear, but APU’s policy has long instilled fear in students.

Zabrina Zablan, a 2016 graduate, said that after the university received a complaint about her relationship with another woman, officials gave her two options: Break up, or lose her position as president of an ethnic student organization and forfeit her pending scholarship.

The 24-year-old Pasadena resident chose to end the relationship, a decision she said led to declining grades and poor choices. The couple eventually reunited, she said, but the damage was done. “I wanted nothing to do with the university at that point. I felt so hurt. The rug was just pulled out from under me, and I was shattered.”

Zablan’s partner, Ipolani Duvauchelle, 27, doubts that Azusa Pacific is ready to make a change.

“Until there is queer leadership who are in charge of implementing policy, there will never be a sustainable change,” said Duvauchelle, a social worker.

Erin Green, a recent APU graduate who said she was asked by administrators to share her experience as a lesbian and consult on changes in policy, said she feels betrayed by the university. College leaders initially indicated to Green that the ban on same-sex relationships on campus was harmful to students and that they wanted to make changes, she said.

She said the university’s chaplain, Kevin Mannoia, told her in May the ban would be removed. The board had plenty of time to be advised of that action, she said.

Mannoia, however, said in an email that while plans were in place to create a ministry program for LGBTQ students, a change in the policy was never promised.

“I feel totally betrayed and exploited,” said Green, 37, the co-executive director of Christian student advocacy group Brave Commons. “They asked me to relive my trauma. We feel violated.”

The reversal, Green said, occurred after APU buckled under pressure from conservative Christian donors and media, which publicized the removal of the ban last month.

An Azusa Pacific professor, who requested anonymity for fear of being fired, said the reinstatement of the ban is a fiscal decision borne out of concern over losing donors at a time when the university is facing dangerous debt.

In emails to faculty, President Jon Wallace said top university leaders were surprised by the school’s debt, which includes $17 million from the 2017-18 fiscal year, a projected $20-million loss for this fiscal year and an additional $61 million in unpaid bonds. In response to the newly projected $20-million loss, the university has put a freeze on hiring, eliminated retirement plan contributions, canceled a scheduled employee raise and reduced benefits, according to the emails.

“When you’re this far in debt, you don’t have a choice to be autonomous,” the professor said, adding that the decision to be inclusive of LGBTQ students and remove the ban on same-sex relationships probably stemmed from a fear of “losing students in the 21st century, when our stance for these students is so backward.”

Citing the university’s large deficit, Green, who now lives in the Bay Area and is studying at the San Francisco Theological Seminary, said the decision “quickly went from God first to money first.”

But David Poole, an APU board member, denied that money is driving the university’s decision.

“Over the last few years, the board and the administration have been working together on how we can most effectively minister and engage all of our students, and in the course of that, there’s going to be missteps and disconnect in communication,” he said.

The university’s LGBTQ pilot program is still being developed, Poole said, adding that two student interns were hired to help shape it. Though some thought an underground LGBTQ student group known as Haven became officially recognized by the university as part of the pilot program, Poole said that’s not the case.

“It is not an official club,” he said. “Haven was never an official club.”

Nolan Croce, one of the students hired under the pilot program, said the Haven group was absorbed by the university as part of its new Student Life-sponsored LGBTQ meetings. Attendance at the meetings has grown to nearly 50 people, up from about seven students who typically attended previous Haven meetings, said Croce, a 21-year-old senior who identifies as queer.

The university’s board has asked students to stop using the name Haven because it says the group is linked with negative connotations and a history of activism, according to Courtney Fredericks, 21, a second intern hired under the school’s new LGBTQ program.

At the new group’s most recent meeting Tuesday, more than 100 students crowded into a room to hear from APU’s vice president for student life, Shino Simons, about the recent changes.

Although the LGBTQ group no longer can invite guest speakers, alumni or community members, Fredericks and Croce are optimistic about the future of marginalized students on campus.

“Just bringing the meetings on campus and letting us advertise, that’s a big step the university has made, and I’m hoping as time goes on, that we’ll have more dialogue,” said Fredericks, a junior who identifies as queer. “We’re not a secular group. Haven is full of Christians. We just want the same space on this campus that other Christian students get.”

Still, other students aren’t so quick to trust the administration and say its actions are a step back in an already difficult battle for LGBTQ inclusion on Christian campuses.

“This feels very frustrating because we were given a right, had a taste of that and it was taken away from us,” said Alexis Diaz, a 21-year-old student government leader who identifies as queer. “That doesn’t feel good.”

alejandra.reyesvelarde@latimes.com

Twitter: @r_valejandra

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.