Must Reads: Comatose and near death, alleged ‘Skid Row Stabber’ may finally gain freedom in decades-old serial case

- Share via

Lying in a bed inside the jail ward at L.A. County-USC Medical Center, Bobby Joe Maxwell’s head lolled to one side as his sister entered the room.

“Bobby. Bobby,” she cooed softly last week as his eyes darted left to right, then up. She wasn’t sure if he was reacting to her voice or just making what little, random, motions he could.

The 68-year-old accused serial murderer was prone under a mess of tubes and wires, his wrists and ankles outfitted in braces to prevent bedsores. Maxwell has been comatose since December of last year, when he suffered a massive heart attack.

An obstruction to Maxwell’s feeding tube nearly caused his death on July 4, according to his relatives. Doctors say his condition will never improve, and in a recent court filing, warned that he may have only months to live.

Legal experts and Maxwell’s loved ones have long questioned why the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office has yet to drop its case against Maxwell, a comatose defendant who is likely to die before he could ever face a verdict.

On Thursday, prosecutors finally relented.

In a statement issued to The Times, the district attorney’s office said it will ask Superior Court Judge Larry Fidler to dismiss all charges against Maxwell at a hearing Friday morning, ending a 40-year legal odyssey that involved a jailhouse informant scandal, tossed convictions and a defendant who claimed he was innocent right up until the moment he lost the ability to speak.

Fidler previously declined a request for an interview through a court spokeswoman.

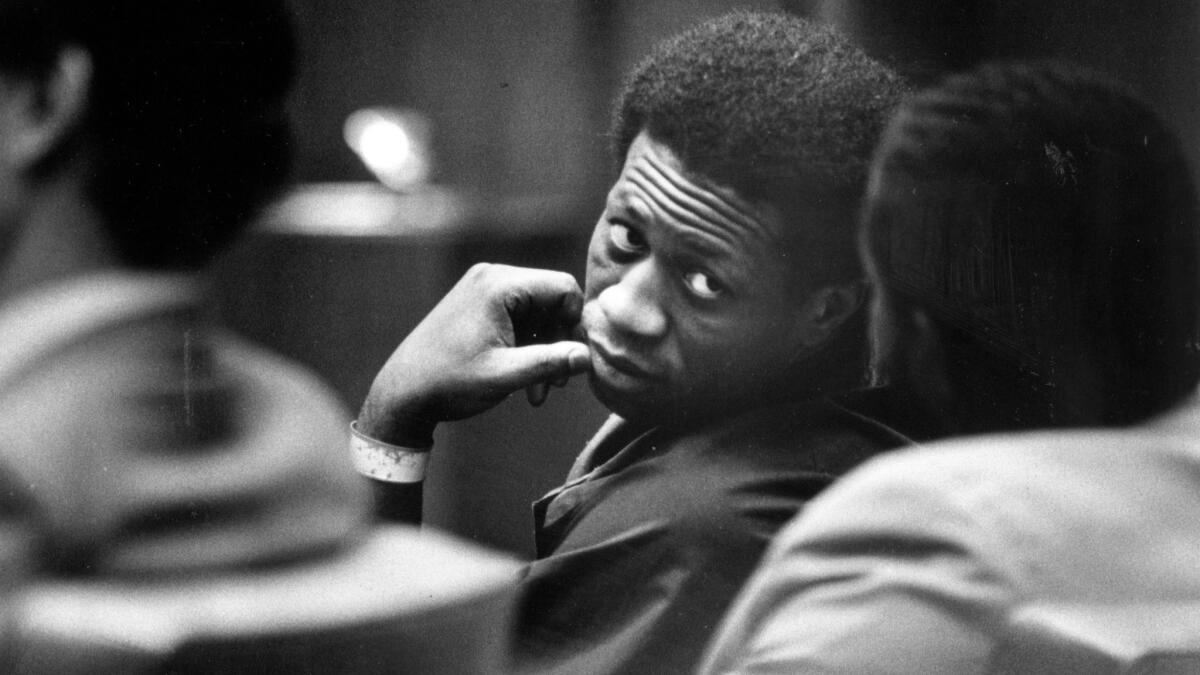

Maxwell has been jailed since 1979, when he was arrested by the Los Angeles Police Department and accused of being the “Skid Row Stabber,” a serial killer believed to have claimed the lives of 10 homeless men in downtown L.A.

A jury convicted Maxwell in two of the murders in 1984, during a trial that largely hinged on the testimony of a jailhouse informant who claimed Maxwell confessed to the murders. Those convictions were later thrown out when it was revealed that the informant was part of a network of Los Angeles County jailhouse snitches who had been fabricating confessions in exchange for lighter sentences from prosecutors.

Maxwell’s convictions were overturned by an appellate court in 2010, but an appeal of that decision delayed the case again until 2013, when prosecutors obtained an indictment to bring Maxwell to trial again for five of the murders. He has remained in custody, ineligible for bail as his attorneys and prosecutors argued over reams of discovery documents and evidence that had been destroyed or lost by the LAPD.

In seeking to dismiss the case, prosecutors cited Maxwell’s deteriorating health, adding that the decision was “not an acknowledgment of factual innocence.”

“Our office learned that Mr. Maxwell was comatose in late December 2017,” district attorney’s office spokesman Greg Risling said in the statement. “Doctors from LAC + USC Medical Center certified that Maxwell would not likely recover in May 2018 but did not do so in writing until July 2018.”

Maxwell nearly died while the district attorney’s office was debating his case.

His sister, Rosie Harmon, said she was awoken by the sound of her phone ringing July 4. A nurse on the other end of the line said her brother’s heart had stopped. Doctors managed to resuscitate him, but the episode only deepened her anger over her brother’s legal situation.

“Why are they still holding onto something?” she asked during an interview last month. “They know he’s not able to get out the bed. He can’t go nowhere.”

In a letter sent to Fidler, who is presiding over the case, the jail ward’s chief physician confirmed Maxwell’s health would not improve, and warned he could die before the end of the year.

“The patient is not able to perform any activities of daily living. He is not expected to regain consciousness. He will continue to require mechanical ventilation in the foreseeable future,” Nickolay Teophilov, the chief physician for correctional health services, wrote in the letter. “He will not be able to participate in the legal proceedings. His prognosis is grave. His life expectancy is shorter than six months.”

When first questioned about its refusal to drop Maxwell’s case in April, the district attorney’s office expressed concern about Maxwell’s need for round-the-clock medical care. Maxwell could be discharged from the jail ward if he is no longer in police custody.

But in a court filing made public in July, the chief executive officer of L.A. County-USC Medical Center, Jorge Orozco, promised that Maxwell would not be “denied or otherwise left without medically necessary care” unless his condition improved. Risling said that promise weighed in the decision to ask for dismissal.

Maxwell’s relatives and lawyers had long argued that a series of missteps led to his wrongful arrest and conviction.

Maxwell was the third person arrested in connection with the killings, but the only one to stand trial. Legal experts and the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals were skeptical of the LAPD’s investigation of the case, questioning the strength of the evidence collected against Maxwell.

The only physical evidence tying Maxwell to the murders was a palm print on a bench near one of the murder scenes, according to police and court records. Maxwell was carrying a knife that was consistent with wounds suffered by some victims of the “Stabber,” but police could not conclusively link it to the slayings. Witnesses who described a suspect walking away from some of the murder scenes could not identify Maxwell at trial either, records show.

“The evidence that they relied on, it wasn’t just weak, it was ridiculous,” said Verna Wefald, who represented Maxwell during the appeals process.

In vacating Maxwell’s conviction in 2010, the appellate court found that the informant who testified at his original trial had lied on the stand and was unreliable. The court described the remaining evidence against Maxwell as “circumstantial.”

At the time of the original trial, even the district attorney’s office noted the case against Maxwell was “weak from an evidential standpoint,” according to the 41-page decision issued by the 9th Circuit.

Maxwell’s attorneys, Fred Alschuler and Pierpont Laidley, have repeatedly accused the district attorney’s office and LAPD of misconduct in their handling of the case. Their claims have ranged from an allegation that the LAPD allowed the real killer to leave California to more recent accusations that prosecutors failed to turn over thousands of relevant documents during discovery, an issue that had frozen the court case for years before Maxwell suffered his heart attack.

Capt. Billy Hayes, who leads the LAPD’s elite Robbery-Homicide Division, said earlier this year that he still believed Maxwell was responsible for all 10 murders.

On the discovery documents, Hayes said investigators likely destroyed evidence in cases where a death penalty verdict had not been reached, or if the appeals process had been exhausted. In Maxwell’s case, physical evidence was destroyed in the three murders he was acquitted of. Some evidence in one of the two slayings he was convicted of was also destroyed.

Legal experts had raised questions about the effort and cost of pursuing the case.

“Situations like this are rare, and the way the system works is one depends on the prosecutor to use their discretion,” said Laurie Levenson, a professor at the Loyola Law School and a former federal prosecutor.

The battle between Maxwell’s attorneys and the district attorney’s office may have only been in search of a moral victory: Even if the judge honors the prosecution’s request to dismiss the case Maxwell is unlikely to ever leave his hospital bed. If the case were to continue, Maxwell would almost certainly die before a jury trial is completed.

But Harmon thinks its critically important that her brother die a free man, rather than an accused serial killer.

Even if he doesn’t know it.

“This man is in his bed. The doctor said he wasn’t coming back to us,” she said. “Clear his name. Let him go peaceful.”

Follow @JamesQueallyLAT for crime and police news in California.

UPDATES:

Aug. 9, 2018, 5:10 p.m.: This story was updated with information about the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office request to dismiss all charges.

This story was first published at 5:00 a.m. on Aug. 8, 2018.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.