When California rounded up Japanese Americans for internment camps, Monterey emerged as the center of the resistance

- Share via

Monterey — Mollie Sumida had lived on this windswept peninsula for years, with friends of all races attending school and slicing abalone on Cannery Row.

The federal government forced her from her home in 1942 when it ordered all people of Japanese ancestry to leave the West Coast and imprisoned 120,000 of them in desolate inland camps.

When the mass exclusion order finally was lifted in December 1944, Sumida was filled with fear about her return.

In nearby Salinas, a group calling itself the Monterey Council on Japanese Relations, which had formed to “discourage” most Japanese from coming back to the coast, was running ads soliciting members. Stories circulated of shootings and arson, of people being refused service at restaurants and denied work in Fresno, Visalia, Delano, San Jose.

In Monterey, though, something extraordinary happened — sparked by the surrounding hostility.

More than 440 people — including novelist John Steinbeck, photographer Edward Weston and poet Robinson Jeffers — signed a petition to welcome the Japanese Americans home. It was published in the Monterey Peninsula Herald on May 11, 1945.

“These families have made their homes here for many years and have been part of the life of our community,” the petition proclaimed. “Their sons are making the same sacrifices as our own boys.... It is the privilege and responsibility of this community to cooperate with the national government by insuring the democratic way of life to ALL members of the community.”

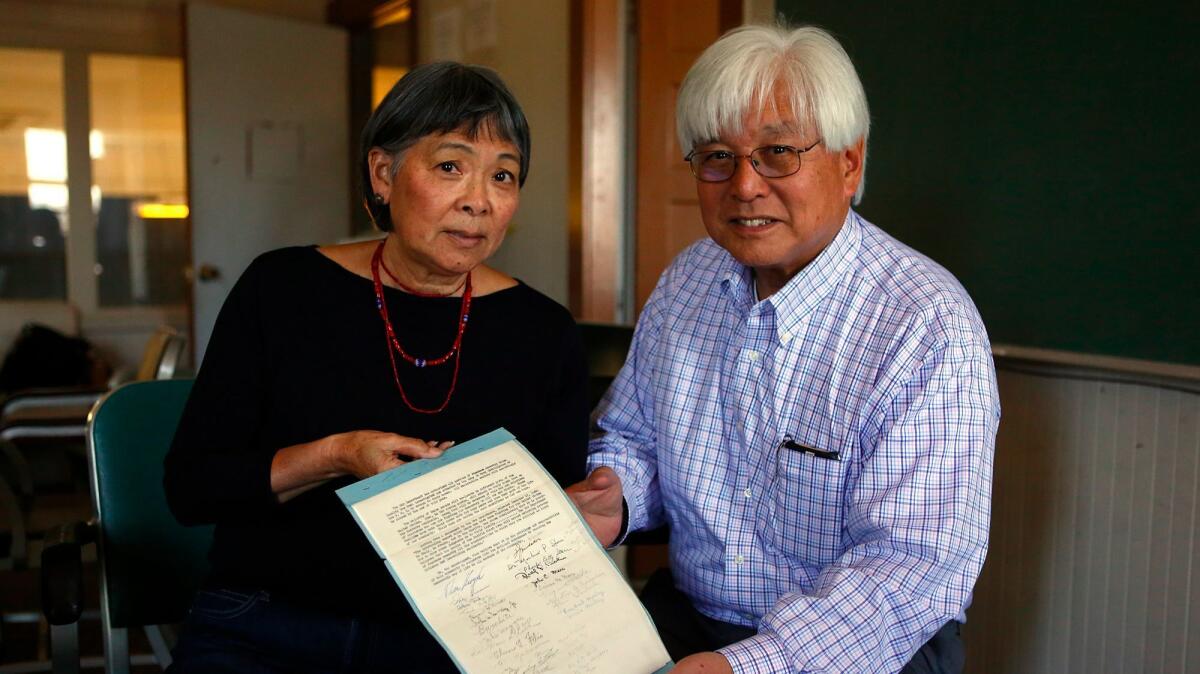

Local historian Tim Thomas rediscovered the original petition in 2013. It remains a source of great pride for local residents that the area’s ethnic diversity, closely knit fabric and progressive nucleus of artists, writers and educators made it stand firm in an ugly time.

Now the seaside town’s little-known story is being shared more widely, in a 10-city traveling exhibit honoring those who, in those heated war years, showed courage and compassion toward Japanese Americans.

The exhibit, sponsored by the Go For Broke National Education Center in Little Tokyo, will travel to places where such bravery was notable. It recently opened in Salem, Ore., which also stood out at the time. A state senator braved political backlash to defend Japanese Americans. Farmers took care of their incarcerated neighbors’ crops. Five white pastors linked arms to stop a mob armed with guns and clubs from destroying the local Japanese Christian church.

The exhibit will visit the central California town of Kingsburg, where Japanese and Swedish farmers worked side by side; Albuquerque, N.M., where young students raised money to buy Christmas presents for incarcerated children in Heart Mountain, Wyo.; Oberlin Ohio, where Oberlin College accepted Japanese American students from the camps.

“To hear these stories gives me hope that, even in a time of chaos and hysteria, Americans can still do the right thing,” said Mitchell Maki, president and CEO of the Go For Broke center, which preserves and promotes the legacy of Japanese American war veterans. “That is a lesson that is so important to us today.”

Clues to Monterey’s unusual stance can be found in the Japanese American Citizens League’s history center and in stories of friendship passed down through generations.

The center chronicles more than a century of relationships between early Japanese fishing pioneers and business partners of various races.

On display are nets, goggles and helmets used by Japanese divers who were astonished by the “carpet of abalone,” as one entrepreneur put it, in Monterey Bay at the turn of the 19th century.

There’s a poster of the Point Lobos Canning Co., a partnership between Japanese marine biologist Gennosuke Kodani and Scottish American businessman Alexander Allan, which processed 75% of the state’s abalone sales before closing in 1928.

A glass case features photos of a German restaurateur, “Pop” Ernest Doelter, and a plastic model of the dish he popularized with Japanese help: abalone steaks, breaded and fried. On one wall hangs an old sign for the Monterey’s Fishermen’s Union, the only multiracial labor organization in the area.

The friendship between the Japanese and Sicilian communities was particularly deep, local residents say. Sicilians hired Japanese fishermen and cannery workers for their sardine operations. Living in adjacent neighborhoods, their children spent so much time together in school and at play — especially on the baseball field — that they learned each other’s ancestral languages, said Thomas, the historian.

Sally Ferrante Calabrese, 92, remembers the “wonderful Japanese fishermen” employed by her family’s cannery. When one of them wanted to buy a home, she said, her father, Sal Ferrante, who signed the petition, got the loan for him because the state’s alien land laws barred Japanese from owning property.

“We thought it was terrible,” Calabrese said of the wartime internment. “They just took everything away from them. It was so unfair.”

Toshiko Ueda said her father, a sardine fisherman, and her mother, a Cannery Row worker, worked with Sicilians while she spent happy days playing kick the can and hiding in fishing nets with her Italian and German friends. An Italian man rented her family an apartment and welcomed them back from the camps.

Larry Oda’s grandfather started Cannery Row’s first Japanese-owned cannery, Seapride, by purchasing land through his white business manager. His mother cleaned houses for a retired colonel, whose family rehired her after the war.

“They were supportive of Japanese Americans because Monterey is a small town,” Thomas said. “They all knew each other. They were all part of the community.”

Sandy Lydon, a Cabrillo College historian emeritus, said another reason for Monterey’s more welcoming attitude was that Japanese presented less direct competition in the fishing industry than they did in the Central Valley’s fields. Japanese largely focused on salmon and abalone, and Sicilians specialized in sardines.

The progressive artistic population also played a big role, putting their names to the petition. Among the signers were Edward Ricketts, a marine biologist and Steinbeck’s best friend — the Doc of Steinbeck’s “Cannery Row” — along with teachers and homemakers, attorneys and business leaders, journalists and clergy.

They were spurred to action after the Monterey Peninsula Herald published an anonymous ad soliciting members for the Monterey Bay Council on Japanese Relations. In letters to the editor, Ricketts compared the group to Hitler while Weston denounced its campaign as a “dastardly approach to race riots.”

The petition found its way into print less than three weeks later. It cited the U.S. Department of War’s call to welcome the community back to the West Coast as “loyal citizens and law-abiding residents” and its praise of the “outstanding service” of Japanese American soldiers. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team/100th Battalion, a segregated Japanese American force, won more military decorations than most any other unit, and bilingual specialists in the Military Intelligence Service have been credited with shortening the war by two years.

“I don’t know of any other place where the community went on record, on paper, to say that the Japanese were welcome to come back,” said Lydon, who wrote a 1997 book on Japanese in the Monterey Bay region. “They did the almost impossible thing of disconnecting the Japanese (Americans) who went to camps from the Japanese Imperial Forces and the Japanese government overseas. What an amazing thing.”

When Thomas discovered the petition rolled up in a drawer in the local Japanese American history center four years ago, he started to cry. “It made me proud to be from Monterey,” he said.

Others feel the same way when they see it for the first time, as some community members did one day recently.

They marveled at Steinbeck’s signature, characteristically in pencil, and searched the other names.

“My typing teacher. My counselor. Until today, I didn’t know they signed it,” said Ann Tsuchiya, Sumida’s mother.

Oda recognized Gertrude Rendtorff — the dean of girls at Monterey High School. “She was strict, a tough old bird, but had a heart of gold,” he said. “Seeing the actual historical document gives you chills. You have people who are doing the right thing.”

Mollie Sumida died five years ago and never saw the original document but it would have thrilled her, Tsuchiya said.

While imprisoned in an Arizona internment camp, Sumida saw the big anti-Japanese ad in the Monterey paper and wrote in to express her hurt that it had been published. Her husband, Yukio, was fighting in Italy for the “American way of life,” she said, with other Nisei, or second-generation Japanese Americans. She thanked her Monterey neighbors for also writing in against the ad.

“I know as long as there are people like that left in this country, all the Nisei boys did not die in vain and what they fought for will live on,” she had said.

Despite her fears, Sumida did return to Monterey with her family after the war. She experienced a few slights — buses would not pick her up, Tsuchiya said — but eventually she thrived. She and her husband started a family nursery and bought a home in an area of town that had once been off limits to them.

“They just did what Nisei did,” Tsuchiya said of her parents. “They put their heads down and worked really hard.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.