Art Kunkin, Free Press publisher who was the pied piper of counterculture in L.A., dies at 91

- Share via

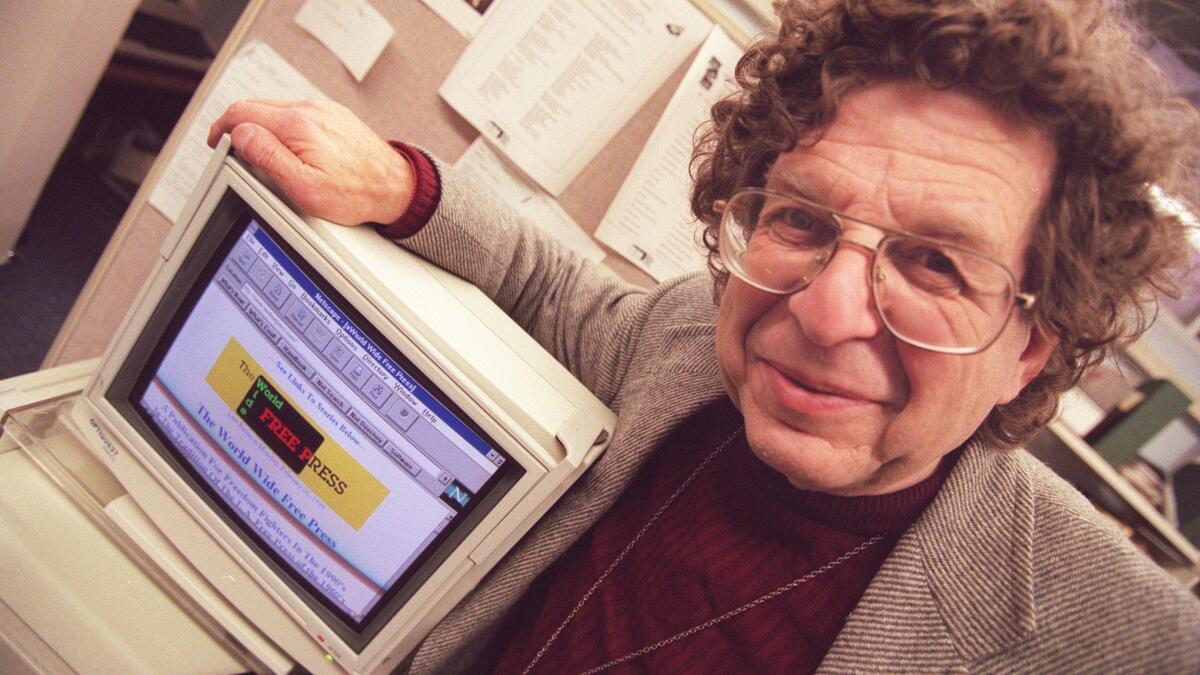

Art Kunkin, the rumpled, curly-haired publisher who arose as the pied piper of L.A.’s counterculture movement in the 1960s with the irreverent but vital Los Angeles Free Press, has died in hospice care in Joshua Tree.

Kunkin, who offered readers a brew of politics, drug talk and rock ’n’ roll, died April 30 at the Institute of Mentalphysics, where he’d lived for years studying philosophy, alchemy and meditation. He was 91. No cause of death was given.

The Free Press — known as the Freep to those who loved or loathed it — rolled onto the streets as L.A. was barreling toward the Watts riots, a tabloid that covered the antiwar movement, the emerging hippie scene and the free speech rallies at UCLA and Berkeley. It was derisive, profane yet sweetly life-affirming.

Inspired by the Village Voice in Greenwich Village and the listener-sponsored radio station KPFK-FM in Hollywood, the Free Press was all things the Los Angeles Times was not.

Kunkin said the mainstream media tended to cover all the events plaguing L.A. as isolated, unconnected events. The Free Press viewed the growing unease in the city as something larger and far more sinister.

“The sense of the 1960s alternative press was that these issues were all connected, that indicated a certain sickness in society,” Kunkin told The Times in 1996.

Launched in 1965, the Free Press was run out the Fifth Estate coffeehouse on Sunset Boulevard. The working environment was familial — reporters, aging beatniks, children, street musicians and the lost and confused milled about in what passed for a newsroom.

The late author Harlan Ellison, then a reporter for the Free Press, said in a 1996 interview that the tabloid seemed to function like “a rambunctious baby with a shotgun in its mouth; it didn’t know when to shoot.”

And that, perhaps, is what upended the paper’s run as the city’s edgy counterweight to the button-down stiffness of L.A.’s traditional media.

For reasons that were never abundantly clear, in the summer of 1969 — as Charles Manson’s followers were terrorizing the city and Neil Armstrong was stepping onto the moon — Kunkin published the names, phone numbers and addresses of 80 narcotics officers in California. “There Should Be No Secret Police,” the headline blared.

The reaction was explosive.

Kunkin was sued by the state and Los Angeles. After two years of legal skirmishes, he was ordered to pay $53,000 in damages, enough to bankrupt the paper. The Free Press limped along for several years before shutting its doors in the late ’70s.

Born in the Bronx in 1928, Kunkin became a tool and die maker. Politically active, he became an organizer for the Socialist Workers Party and later worked for the party’s paper, the Militant. He came west in the 1950s, continuing to work on an assembly line.

In 1964, he was asked to publish an eight-page newsletter for the Renaissance Pleasure Faire in L.A. Kunkin filled it with strange and fantastical stories — Joan Baez’s supposed tax strike, an obscenity bust during a showing of the film “Scorpio Rising.”

The first issue of the Los Angeles Free Press was printed in July 1964. Along with his wife, Abby Rubinstein, Kunkin put up $200 to bankroll the paper, money spent mostly on postage to solicit advertisers. The couple edited the paper at their dining room table, writing headlines, cropping photos, keeping their fingers crossed it would all somehow work.

The paper sold for a quarter, nearly double what The Times cost at a newsstand. The lifeblood of the Free Press were sex ads, which were unwelcome in traditional family newspapers. By 1969, circulation had swelled to 100,000 and the paper had growing political clout.

The Free Press turned Kunkin into a high priest of resistance in L.A. He swapped story ideas with Yippies founder and satirist Paul Krassner, discussed music with Frank Zappa and hung out with Timothy Leary. In 1973, with his legal bills due, Kunkin closed the Free Press.

It was revived briefly after it was purchased by Hustler publisher Larry Flynt and then shut for good when Flynt was shot in 1978.

For a while, Kunkin taught journalism at Cal State Northridge and then became involved with several efforts to revive the Free Press. None lasted.

Finally he faded away, heading off to Salt Lake City where he studied alchemy at the Paracelsus Research Society for seven years. He moved to the Joshua Tree compound after returning to California.

Lionel Rolfe, the late Herald Examiner columnist and author, said he first met Kunkin in the 1960s at the Sunset Boulevard coffeehouse. Rolfe wrote in a blog that his old friend remained as spirited and bohemian as ever at the desert institute, living in a trailer surrounded by a mountain of books and records.

“Those days are forever gone,” Rolfe wrote of the Free Press days. “Now Art reads The Times, mainly the obituaries to see which of his old Marxist comrades has died.”

Kunkin’s first two marriages ended in divorce. A third wife, Elaine Wallace, died in 2017. He is survived by two daughters, Anna and April Fountain.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.