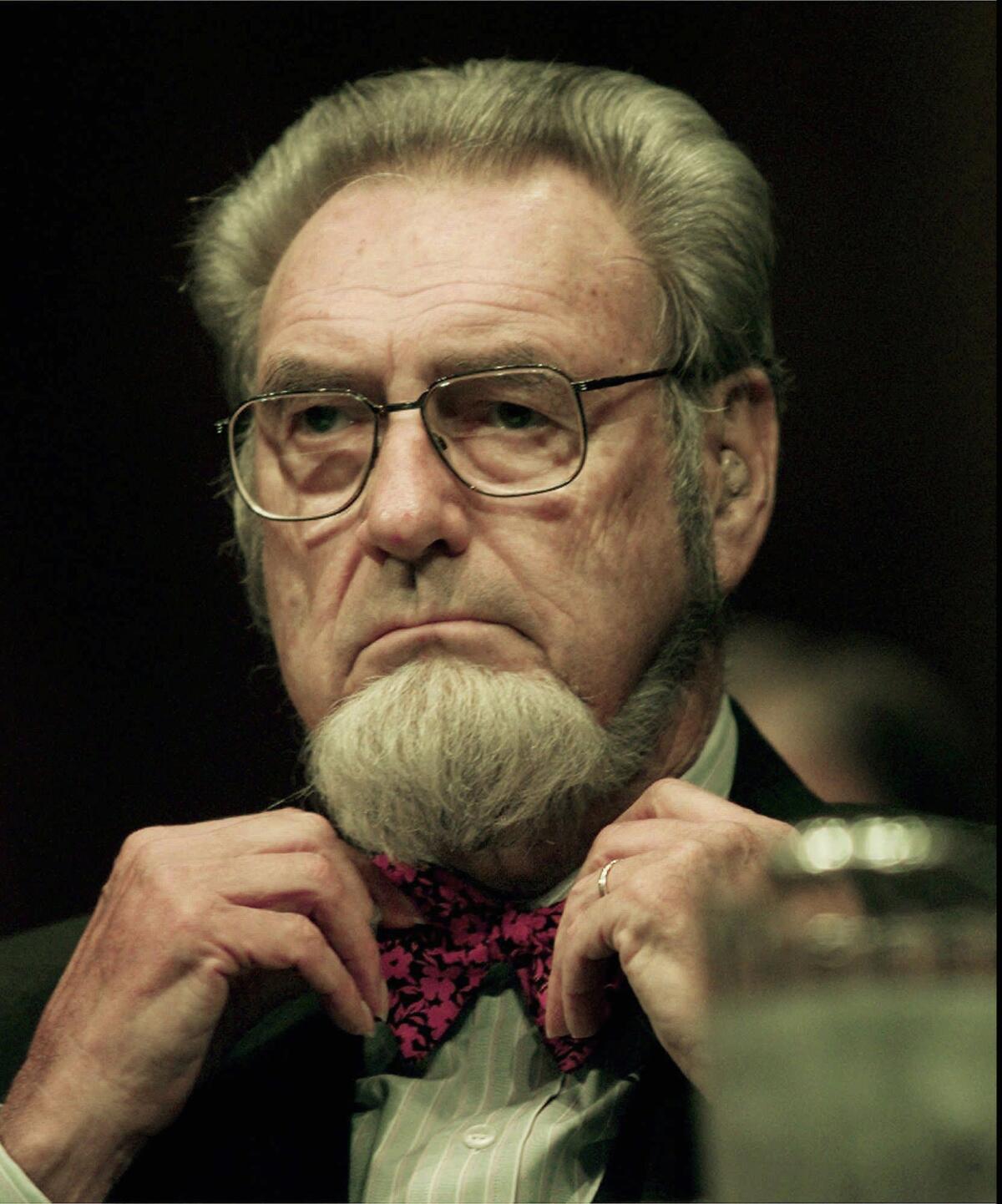

C. Everett Koop dies at 96; former U.S. surgeon general

- Share via

In the mid-1980s, the emerging AIDS epidemic was a high-profile target of vocal conservatives. Politicians and the religious right called for sweeping measures against those diagnosed with AIDS, including quarantine of patients, mandatory screening of homosexuals for the AIDS virus and a host of other measures that would victimize patients and keep the disease and the diseased hidden from public light.

But they did not reckon with Dr. C. Everett Koop, the religious and conservative surgeon general of the United States appointed by President Reagan. In October 1986, Koop issued a long, cogently written report on the imminent crisis arguing that “this silence [on AIDS] must end.”

Viewed with horror by the right, the report called for the widespread use of condoms to halt the transmission of the virus and sex education for children as young as third-graders to promote “safe sex.” Despite his own strong opposition to abortion, he recommended the procedure be mentioned among options for pregnant women with the AIDS virus.

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2013

He followed up in 1988 by circumventing reluctant administration officials to mail an educational pamphlet about the disease to 100 million U.S. households — the largest federal mailing on public health ever. Critics charged that he was promoting a “gay agenda” and favored abhorrent sexual practices, but Koop responded that “You may hate the sin, but love the sinner.… We are fighting a disease, not a people.”

Koop died Monday at his home in Hanover, N.H. , according to Derik Hertel, director of communications at Dartmouth College’s Geisel School of Medicine. The former pediatric surgeon was 96.

AIDS was not the only field where the outspoken Koop had a large impact. Unlike surgeons general before and after him, he used the position as a powerful bully pulpit to promote better health behaviors.

In February 1982, Koop released a scathing report on smoking, proclaiming it “the most important public health issue of our time.” He cited the health risks of smoking and called for the U.S. to become a “smoke-free nation.”

He followed up in 1988 with the landmark report “The Health Consequences of Smoking-Nicotine Addiction,” which equated nicotine addiction with addiction to cocaine and heroin. The report cited the links between smoking and a variety of cancers, highlighted the dangers of second-hand smoke to the non-smoker and called for warning labels on tobacco packages.

Koop’s efforts led to sea changes in U.S. attitudes toward both AIDS and smoking. At 6-foot-1, sporting the square-cut beard favored by his Dutch ancestors and the white, braided uniform of the U.S. Public Health Service, he became the widely recognized face of public health.

“Dr. Koop was not only a pioneering pediatric surgeon, but also one of the most courageous and passionate public health advocates of the past century,” said Dr. Wiley W. Souba, dean of Dartmouth’s medical school. “He did not back down from deeply rooted health challenges or powerful interests that stood in the way of needed change. Instead, he fought, he educated, and he transformed lives for the better.”

Federal service, however, was the second act of his career. In 1948, at age 31, he was appointed surgeon-in-chief at Philadelphia’s Children’s Hospital. At the time, he was one of only six pediatric surgeons in the country.

In the 1940s, infant mortality rates following surgery approached 95% and surgeons were reluctant to operate on babies. Placing a child under general anesthesia was considered too risky. Doctors often insisted that surgery be delayed until children were older.

‘’There was no basic science,’’ Koop said. ‘’It all had to be worked out.… Children didn’t get a fair shake in surgery, and I saw this as one of the great inequities in medicine. Children had as much wrong then as they do now. And yet we were so ill-equipped to take care of them.’’

Determined to change that, he directed his energies toward building the finest surgical staff possible at the hospital. In 1962, he established the country’s first surgical intensive-care unit for newborns. He also promoted the use of intravenous nutrition, which was rare at the time.

He became famous for several operations in which he successfully separated conjoined twins, including one procedure in which one twin had to be sacrificed to save the other. ‘’The nurses couldn’t believe it,” he said in a 1986 interview. ‘’Here was pro-life Koop about to kill a child.”

During his career, he performed more than 17,000 inguinal-hernia repairs and more than 7,000 surgeries to correct undescended testicles. He developed procedures for correcting lack of continuity of the esophagus and the use of shunts to treat fluid accumulation in the brain.

He played a major role in eliminating the use of X-rays to measure the size of children’s feet in shoe stores, arguing that the radiation risks far outweighed any potential benefits.

Charles Everett Koop was born Oct. 14, 1916, in Brooklyn, N.Y. Friends called him Chick, as in “Chicken Koop,” and the nickname stuck. As a child, he was frequently taken by his grandparents to the boardwalk on Coney Island. On one such trip, he saw disabled infants in incubators in a display, and he later said that triggered his interest in surgery.

He graduated from Dartmouth in 1937 and from Cornell Medical College in 1941. During World War II, he performed his residency at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and conducted research on blood substitutes for the military.

In the late 1970s, he wrote “The Right to Live, the Right to Die,” arguing passionately against abortion and in favor of rights for infants born with severe birth defects. With Christian activist Francis Schaeffer, he made a series of films called “Whatever Happened to the Human Race?” The films argued that abortion was the first step on a slippery slope that could lead eventually to genocide.

As Koop neared retirement age, Reagan saw him as a kindred spirit and nominated him to become surgeon general. The nomination provoked a firestorm of criticism among congressional liberals, who blocked his nomination for a year out of fear that he would apply his conservative and religious views to his public office. He was confirmed only when he promised that he would not use the post to promote his religious views.

He lived up to his word, surprising and delighting his early critics — and angering conservatives who had initially supported him — by applying a scrupulous public health approach to every policy issue that confronted him, regardless of his personal views.

In 1987, Reagan directed him to prepare a report outlining the adverse effects of abortion on a woman’s health. By 1989, he concluded that there were no good scientific studies one way or the other, notified Reagan of his findings and ordered his staff to drop the report. Ultimately, however, the report was issued under his name without his approval and its release led in part to his early resignation from the post in 1989.

In 1991, he received an Emmy award in the news and documentary category for a five-part TV series on healthcare reform.

Koop was an advisor to President Clinton’s health-reform efforts and served as chairman of the National Safe Kids Campaign. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1995 for his public health efforts and received numerous other awards.

In 1997, Koop established a website called drkoop.com to provide health information to the public. Although an initial public offering made Koop a wealthy man, the site was criticized for mixing health information with paid advertisements without clearly distinguishing between them. The site went bankrupt in 2001.

The company ultimately settled a lawsuit by investors claiming that it had made them false promises. Koop also made a series of health-related videos, sold in pharmacies, that were not particularly successful.

Koop’s wife of 68 years, the former Elizabeth Flanagan, died in 2007. He is survived by his second wife, the former Cora Hogue, three children from his first marriage, seven grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

Maugh and Cimons are former Times staff writers.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.